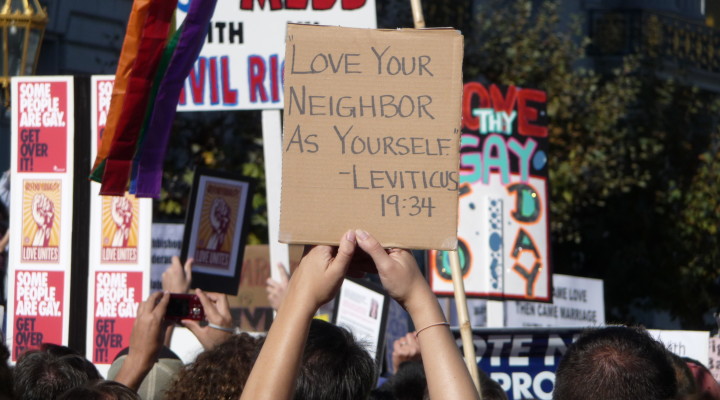

It was just about a year ago when Baptist writer and minister Corey Fields wrote a column critiquing a spate of “religious freedom” bills pushed through statehouses around the country.

Indiana’s version was one of the more high-profile measures. It was designed to “protect” the religious liberty of Christian business owners who refuse to serve gay customers. Arguing religious freedom, Hobby Lobby earlier won the right to control the kinds of contraception its female employees can get through company-sponsored health insurance.

Like many others, Fields was perplexed by this approach to a fundamental American right.

Corey Fields

“Religious freedom used to be about gaining the protection of the law, not putting oneself above the law,” he wrote in the April 2015 column for Baptist News Global.

A year later, Fields is among many who are still scratching their heads as yet more efforts to use, or misuse, the concept of religious liberty are introduced in different states.

One of the more recent came amid a barrage of national media coverage in Georgia, where Gov. Nathan Deal vetoed House Bill 757, which claimed to protect ministers from being forced to conduct same-sex marriages. Major businesses, including the National Football League, had threatened to boycott the state if the measure was passed.

The events inspired writers, historians, legal experts and ministers to grapple with the topsy-turvy nature of religious liberty in the United States.

Cultural privilege threatened

One of them is Patricia Miller, a Washington, D.C.-based author and journalist who wrote a March 28 Religion Dispatches piece titled “Is religious liberty whatever anyone says it is?”

She cited the Georgia legislation as well as recent Supreme Court hearings on challenges to contraceptive mandates.

“We’ve moved beyond any nuanced conversation about the parameters of the right of faith-based actors to claim exemptions from broadly applicable laws and into wide reaching claims that religious liberty is essentially anything for anyone who has a religious objection,” Miller wrote.

That religious freedom has different meanings is really nothing new in American history, says Bill Leonard, professor of Baptist studies and church history at Wake Forest University School of Divinity.

“The definition tends to be very flexible depending on the particular times people find themselves in,” Leonard says.

Nor is it new that the concept can be used harshly at times.

Bill Leonard

“In American religious history, Americans give religious liberty, but they give it grudgingly.”

Or it isn’t given at all. Leonard notes that in some states, churches were taxing entities well after the adoption of the Constitution and the Bill of Rights. Puritans exiled Baptists from New England and hung Quakers. Mormons were often shot on the streets and Catholics battled Protestants.

“And now we have one presidential candidate saying we should keep Muslims out and another saying we should be patrolling Muslim neighborhoods,” Leonard says.

So religious liberty is often defined by who is in power.

“It depends on who the religious majority is and who the minority is and who they want to keep out.”

But he adds that much of the controversial “religious liberty” legislation appearing in U.S. statehouses results from once-majority Protestant Christians sensing their loss of cultural standing.

“A lot of people are misinterpreting that as infringing on their religious liberty, when it’s actually infringing on their cultural privilege,” Leonard says.

‘It comes down to fear’

While there has never been unanimity of opinion about religious freedom, the Constitution offers guidelines, says Brent Walker, executive director of the Baptist Joint Committee for Religious Liberty.

It includes having the freedom to believe and worship as one chooses.

Brent Walker

“Religious liberty means you are able to act on those beliefs in the world without being unduly interfered with by the government,” Walker says.

But there also are times when the government can intervene — especially when religious action can harm others or society, he adds.

“Some people think religious freedom is absolute, that they can do and believe whatever they want even if it results in discrimination.”

Baptist theology, namely the idea of soul freedom, also promotes religious liberty, Walker says.

“The soul freedom each of us enjoys means we want to ensure it for everybody — we want religious liberty for all.”

But all bets are off when people become afraid of all kinds of projected outcomes, says Fields, associate pastor at First Baptist Church in Topeka, Kan.

“It all comes down to fear.”

He recalled a 2010 campaign to ban sharia law in Oklahoma. The amendment, which was approved by voters, forbade state judges from using Muslim law in their decisions. It was overturned by higher courts because proponents couldn’t demonstrate a compelling need for the measure.

“It was a solution in search of a problem,” Fields says. “It goes back to fear.”

He saw the same motivation behind the Georgia bill vetoed this week. Ministers don’t need a new law protecting them if they refuse to conduct same-sex weddings because they already have that protection, he says.

Fields says he has turned down couples when there was clear evidence their relationship was unhealthy.

“I have turned down a few heterosexual couples and I am totally free to do that. The government’s recognition of same-sex relationships doesn’t change anything.”

Some believe they will be jailed for speaking against gay marriage or for simply being Christian, Fields says. These ideas are contributing to the redefining of religious freedom around the country.

“People have genuine fears, but I think they are unfounded.”