On May 2, 1963, more than 1,000 students walked out of class in Birmingham, Ala. They gathered at Sixteenth Street Baptist Church to march downtown as part of the ongoing Southern Freedom Movement, of which Birmingham was the epicenter. Children, organizers thought, would make a powerful public display of the moral and legal cause of the movement.

But the idea had been controversial even among the organizers. On the one hand, children might have lesser legal exposure than their parents. They would not face backlash from white employers, risking a firing and the economic hardship that would follow. And, importantly, many children and teens wanted to participate.

Greg Jarrell

Martin Luther King and other Southern Christian Leadership Conference leaders were reluctant about the strategy at first. They knew too well the danger that would face those young participants. But James Bevel, a Birmingham minister, convinced them the strategy was the right one. He took the lead in organizing the Children’s Crusades.

“They locked more than 1,000 in jail. And children still poured into the streets for a full week of protests.”

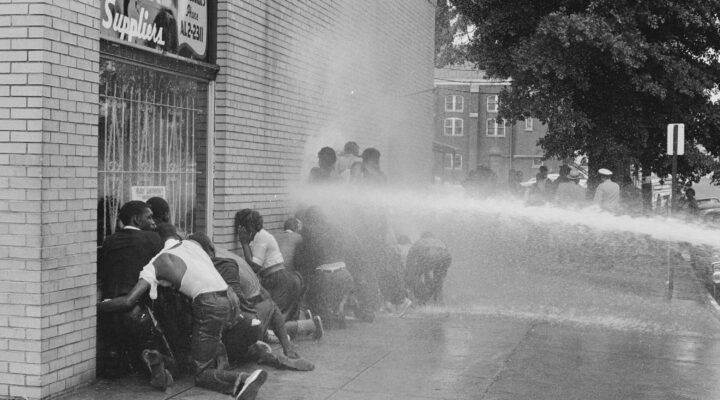

You’ve seen the images. Police mercilessly assaulted those children with dogs and fire hoses and night sticks. They locked more than 1,000 in jail. And children still poured into the streets for a full week of protests. The Children’s Crusades reinvigorated the Southern Freedom Movement that some feared was losing steam in May 1963.

On the exact same day, May 2, 1963, Pastor Carl Bates of First Baptist Church of Charlotte, N.C., an all-white Southern Baptist congregation, published his weekly newsletter column, sent out to more than 1,000 member households. In it, he announced a series of sermons on “the Christian home.” For Sunday evening services in that series, he would direct his comments to questions posed by the youth of the church. The first sermon in the series had the title “Let’s Talk about Dancing.”

How did this happen?

As I worked at the research and writing and thinking that became Our Trespasses, one of the persistent questions I wanted to understand went something like this: “How did this happen?”

By this, I meant urban renewal generally, but I also meant more specifically the ways white Christians and churches were part of every phase of Charlotte’s urban renewal projects, from the planning to the profits.

With how, I was trying to get specific. The question may seem kind of obvious: It happened because that’s what happens in systems of white supremacy. But under the obvious, I wanted to know what specific components of white American society helped to create and reproduce a massive injustice that was so blatantly abhorrent, and yet seemed natural and uncontroversial as it was happening.

A single family home surrounded by parking lots in Reno, Nevada. (Photo by George Rose/Getty Images)

The scars of urban renewal

In Charlotte, which I suppose to be very much like many other American cities, there were white civil rights “leaders” out in public helping to push for the first urban renewal project, and then four more after that.

Even the most conscious of our local white faith leaders could not understand how they were acting inside the racial contract in a way that asserted their dominance over space and people, even as they advocated for a more abstract idea of “rights” in the context of the Civil Rights movement.

My question was not passing curiosity. The scars of urban renewal still mark the cityscapes of places around the country. A new version of the same old story is happening as well. I’m watching my neighborhood being hollowed out around me, and there is no small number of white Christians who have been finding advantageous real estate deals on our side of town over the past couple of years. The great Realtor© in the sky keeps directing them over here, in his mysterious ways.

Maybe they just let the MLS listings fall open and drop their finger into a place and start writing contracts from there.

The racial contract

Whatever was operating in urban renewal does not seem to have died. It passed on to the next generation. Understanding “it” — some component part or parts of the system of white supremacy — is essential material, political and spiritual work.

“How were people able consistently to do the wrong thing while thinking they were doing the right thing?”

The philosopher Charles Mills asks a similar question: “How were people able consistently to do the wrong thing while thinking they were doing the right thing?”

The terms of the racial contract, Mills’ conception of the unspoken agreement that binds our society together and forms the basis of moral and political life, lock those of us who are made white into “moral cognitive dysfunction.”

Those of us who are white, as a group, Mills says, “will experience genuine cognitive difficulties in recognizing certain behavior patterns” — say, concern about dancing while disregarding Jim Crow — “as racist, so that quite apart from questions of motivation and bad faith they will be morally handicapped simply from the conceptual point of view in seeing and doing the right thing.”

Mills does not think this condition is necessarily permanent, nor that it is a trap. The normative culture in white society is built around studied ignorance. It is reproduced through “evasion and self-deception.”

Avoiding the truth

Avoiding the truth, you might say, and building educational and political systems around such chosen ignorance. The obvious examples we see now are the ridiculous Prager University curricula you may have seen on the internet, the state of Florida under Ron DeSantis in general, or the fact that the school libraries at my children’s schools were closed for the first two weeks of school because administrators had to review all the books over some imaginary scare by the Moms for Liberty.

But underneath all that clownish stuff are many more insidious examples of how racism has been the water we swim in.

Mills’ antidote to moral cognitive dysfunction is the courage to resist studied ignorance and evasion and self-deception. He quotes the Swedish writer Sven Lindqvist: “It is not knowledge we lack. What is missing is the courage to understand what we know and draw conclusions.”

“What is missing is the courage to understand what we know and draw conclusions.”

White folks have a choice — that is, to become morally serious. To celebrate dancing, and to dance while we undo oppression.

There always have been those who have shown us an alternative to “moral cognitive dysfunction” — abolitionists and Freedom Riders and renegades and race traitors, John Brown and Anne Braden and Lillian Smith and Clarence Jordan and Joan Trumpauer and so on. What most of us have lacked, though, is the sense to be scared of the right thing: not dancing, but our silent consent to the horrors of white supremacy.

Greg Jarrell is co-founder and Chief Door Answerer at QC Family Tree, a community of rooted discipleship in the West Charlotte, N.C., neighborhood of Enderly Park. Greg shares life there with a host of neighbors who have become family, as well as his wife, Helms, and sons, John Tyson and Zeb. He is the author of A Riff of Love: Notes on Community and Belonging.