By Ken Camp

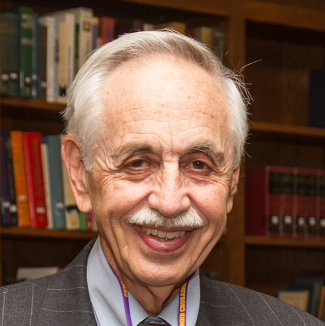

Polarized politics in 21st century America are rooted in the cultural conflict of the 1960s, with race and religion at the forefront, historian Wayne Flynt told a conference at the University of Mary Hardin-Baylor in Belton, Texas.

Flynt, emeritus professor of history at Auburn University, spoke on “Baptists, Evangelicals and Modern American Politics.” The UMHB College of Christian Studies sponsored the Oct. 12-13 conference on “Baptists and the Shaping of American Culture.”

“Those who seek the origins of the deep polarization that has created red and blue America — where we live in neighborhoods of like-minded people, sip latte or wine in similar ideological coffee shops or bistros and attend churches surrounded either by Democrats or Republicans who hire a like-minded pastor — might begin by looking in the 1960s,” Flynt asserted.

“Those who seek the origins of the deep polarization that has created red and blue America — where we live in neighborhoods of like-minded people, sip latte or wine in similar ideological coffee shops or bistros and attend churches surrounded either by Democrats or Republicans who hire a like-minded pastor — might begin by looking in the 1960s,” Flynt asserted.

Prior to that tumultuous decade, Flynt said, many white Baptist pastors in the South did not vote, emphasizing spiritual preparation for eternity over temporal politics. Those who did voted primarily for Democrats, the de facto single party of the South.

Then came the 1960s, he said, when “secularizing American culture gave evangelicals a series of vigorous kicks in the solar plexus.” That, he said, mobilized many white evangelicals around issues like opposition to abortion and gay rights and in favor of public expressions of religion.

“Religious people of all denominations, especially in the South but by no means limited to that region, began to vote ever more heavily for Republicans,” he said. At the same time, he said, race continued to divide Americans, including evangelical voters.

“Most thunder from the Religious Right originated in white churches,” Flynt said. While most African-American evangelicals in the South “shared common ground with their white brethren” on issues such as homosexuality, he said, “they also distrusted the Republican Party, were economically liberal and voted overwhelmingly Democratic.”

“Strange bedfellows, these evangelicals,” Flynt quipped.

Flynt said African-American evangelicals overwhelmingly voted for Barack Obama in 2008, while the strongest support for Republican John McCain came in overwhelmingly white, working-class, rural counties in the South where about one-third of residents identified as Southern Baptist.

While evangelicals make up an increasing percentage of Republican Party voters, they appear to be driven by issues other than theology, Flynt observed.

“Evangelicals seem poised for a massive turnout on behalf of Mormon Mitt Romney, a candidate that Republican Party primaries demonstrated they clearly don’t even like,” he said. “Furthermore, many of them consider his religion a heretical cult.”

Flynt wondered if the trend might lead to even more unlikely political alliances such as evangelical support for an atheist libertarian or pro-life Buddhist. Another possible scenario, he speculated, is that a “final evangelical barrier” might push white evangelicals back to their pre-1960s posture of disengagement from secular politics.

“Politicized religion is really complicated,” he concluded. “Before generalizing about evangelicals, political pundits need to do lots more homework. Are the people they describe black, white or Hispanic — poor or rich — male or female?”

Flynt said both the media and academic circles have slowly begun to discover that “southern evangelicals are not marginalized, simple-minded, displaced persons wandering in a desert of American culture and politics.”

“They are not dumb, uneducated or unsophisticated,” he said. “Neither do they always agree with each other or vote the same way.”