Baptist Joint Committee for Religious Liberty in Washington, D.C., is and has been an institution long championed by moderate and progressive Baptists for its defense of religious liberty for all people. Since 1936, Baptists from across geographic and racial lines have partnered together to protect and defend the principle of religious liberty.

At least, that is the story many of us, including the BJC, have been told.

While I was serving on the board of BJC, Tisa Wenger, a historian of American religion, published her work Religious Freedom: The Contested History of an American Ideal. In this work, Wenger shows how the idea of religious freedom often has functioned to privilege and prioritize the power and authority of white Americans. Focusing on the importance of religious freedom has intentionally been utilized to eclipse other rights and freedoms, particularly those of people of color.

One culprit of this use of religious freedom, she argued, was BJC.

In response, during my tenure on the board, BJC set out to interrogate its history and challenge the standard narrative of BJC’s founding. This dive into the organization’s history sought to help give renewed attention to the ways in which race and religious freedom are intertwined.

“The organization often neglected directly or indirectly the concerns of its predominantly Black constituents.”

After my time on the board concluded, I independently continued researching BJC’s history. Recently, I published an article in The Journal of Church and State titled, “Race, Religious Freedom, and the Institutional Limitations of the Baptist Joint Committee on Public Affairs.” In this piece, I document that despite the organization’s multiracial origins, BJC had much stronger relationships with its predominantly white Southern and American Baptist constituents. As a result, the organization often neglected directly or indirectly the concerns of its predominantly Black constituents. The piece examines the organization from its founding to the early 1970s.

Black Baptist participation in BJC

From its inception, one of the biggest challenges BJC faced was establishing meaningful relationships with Black Baptist denominational leadership. After an informal period of cooperation in the 1930s and early 1940s, BJC formally organized in 1946 as a cooperative venture between the Southern Baptists and American Baptists as well as the historically Black National Baptist Convention Inc. and National Baptist Convention of America. From the beginning, however, BJC’s leadership was unsuccessful in soliciting individuals to serve as representatives on the board from these Black denominational bodies.

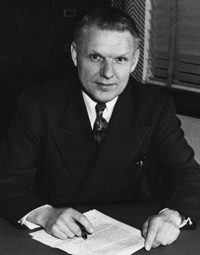

J.M. Dawson

For decades, BJC leadership struggled to navigate the bureaucracy of Black denominational bodies. Executive Directors J.M. Dawson and Emmanuel Carlson lacked the relationships and friendships within Black denominational bodies they held within the predominantly white SBC and ABC. Regularly, these BJC leaders sent letters requesting basic information from the NBC and NBCA. They often acknowledged the limitations of their knowledge.

For example, under Carlson’s leadership of BJC he wrote to NBCA President C.D. Pettaway in the late 1950s requesting someone be appointed to the board to represent the NBCA. Carlson confessed in the letter, “I am not sufficiently acquainted with your organization to know whether it comes within your power to designate representation from your convention.” In this letter, BJC’s leadership confessed they did not know the mechanisms through which one of its four major denominational partners appointed board representation.

BJC’s lack of relationships with and institutional knowledge of predominantly Black Baptist bodies meant the direction of the organization more often was steered by white Baptists from the SBC or ABC.

Pay to play

Board members from the ABC and SBC also were not the most welcoming of Black Baptist representatives. Issues of money and financial contributions were indicative of who held the power in the organization. As the ABC and SBC were the two largest denominational contributors to the work of the BJC, they held the most sway in the organization.

In the early years, BJC operated within a rather precarious financial position. Money was tight. White Baptist denominational representatives regularly addressed the lack of financial contributions coming from the NBC and NBCA. Some Black Baptist denominational representatives even confessed they felt bad attending board meetings if their organizations had not been able to contribute that year.

In 1959, William Lipphard, a representative of the ABC, took it upon himself to write a series of letters to NBC President J.H. Jackson. In his correspondence, Lipphard refused to accept Jackson’s reasons why the NBC was unable to financially contribute to BJC at the time. In one letter, Lipphard concluded, “I hope that you will be able to see your way clear to come to the help of this committee.” In another he wrote, “It is indeed most regrettable and deplorable that our Negro brethren are taking almost no interest in the work of this important joint committee.”

The emphasis on financial contributions by many of BJC leadership and board members did not create a welcoming environment for Black Baptist denominational leadership to participate in the work of the organization. This coupled with the lack of informal relationships and denominational bureaucratic knowledge made Black Baptist participation difficult.

Religious freedom — a singular issue

BJC’s almost singular focus on religious freedom additionally created barriers to Black Baptist participation. Although the organization was initially named the Baptist Joint Committee on Public Affairs, the organization almost solely addressed religious freedom. While some board members pushed the organization to address issues like civil rights, others would respond that such issues were outside the purview of BJC.

Southern Baptists like Walter Pope Binns, president of William Jewell College, adamantly opposed BJC addressing “moral and social problems” including segregation. Binns contended the SBC had established the denomination’s Christian Life Commission to address issues like segregation and civil rights. Should BJC address issues of race, he argued, the organization would be stepping outside its mandated agenda from the SBC.

“As Black Baptist churches throughout the South were bombed, the organization did relatively little to cover these issues as issues of religious freedom.”

As an intended or unintended consequence of the SBC’s unwillingness to fund two organizations that might address issues of race and segregation, BJC was limited in its agenda to defend religious freedom. As Black Baptist churches throughout the South were bombed, the organization did relatively little to cover these issues as issues of religious freedom.

Emmanuel Carlson

In 1960, BJC Executive Director Emmanuel Carson received a phone call followed by a letter from a legislative consultant regarding “the predicament of Rev. T.D. Wesley.” This legislative consultant relayed correspondence from Wesley, a Black pastor, who had served two churches in Shelby County, Ala.

In Wesley’s correspondence, he wrote of his experience being harassed and kidnapped by 15 to 20 members of the Ku Klux Klan “posing as law officers.” They accused him of preaching integration, put him “in one of their cars and carried (him) into the woods,” beating him “unmercifully.”

After getting out of the hospital, the harassment continued and “a dummy was thrown on (his) porch with red paint on it and a note taped to it stating … to get out of the south in 10 days.” He agreed to the demand but continued serving as pastor of his two churches. On Sunday, Nov. 16, 1958, his New Mt. Moriah Baptist Church was shot at 17 times. He resigned.

His letter concluded: “These and many other acts of violence and intimidation made it impossible for me to continue to live or to preach in what I must sorrowfully call my former home. … Can this be America? Yes, this is America. What protection will America give to her loyal citizens?”

This legislative consultant relayed Wesley’s correspondence to BJC presumably because they thought BJC would do something about it. In my research, I could not find any response from Carlson or BJC.

The challenge of loving Baptist Joint Committee

Both Southern Baptists and American Baptists are implicated in the history of BJC neglecting the voices of its Black Baptist constituents. There is a unique challenge, however, for formerly Southern Baptists today in celebrating and indeed loving the work of BJC.

For those individuals who once were Southern Baptist and perhaps now find themselves participating in CBF or the Alliance of Baptists, BJC is cherished for its defense of religious liberty for all people. BJC carries on the legacy of Roger Williams, John Leland, Isaac Backus and many other historic Baptists who fought for and established religious freedom in the United States. There is no difficulty in loving BJC in this regard.

For formerly Southern Baptists, however, BJC represents something more. As moderate and progressive Southern Baptists lost control over institution after institution in the 1980s and 1990s, BJC stayed the course. The “joint” nature of BJC inhibited the SBC’s more conservative faction from exerting its influence over the organization and as a result the SBC withdrew and in 1997 founded its Ethics and Religious Liberty Commission.

“BJC represents part of the past that was not taken away from formerly Southern Baptists.”

In this way, BJC represents part of the past that was not taken away from formerly Southern Baptists. It is loved and cherished because it did not “fall” as other institutions did. It helps historically anchor moderate and progressive Baptists in the South. Loving and cherishing BJC in this way, however, remains part of loving and cherishing what was lost. It remains part of loving and cherishing the SBC’s tradition of treating religious freedom as a discrete and isolated issue, completely unrelated to other rights and social issues.

The challenge of loving BJC for formerly Southern Baptists rests in the reality that the organization is loved for both good and bad reasons at the same time. It is loved explicitly because it institutionally embodies the Baptist commitment to religious freedom for all people. It also is loved implicitly because it serves as a continuation of power and control among white, moderate Baptists in the South who historically fought primarily for themselves.

Disentangling these two loves is stubbornly difficult.

The organization has taken great strides in recent years to address its past failings. I have seen this firsthand as a former board member. From addressing Christian nationalism through the Christians Against Christian Nationalism campaign to interrogating the relationship between race and religious freedom, BJC has done much good work over the past few years.

It is important, however, to remember the “joint” nature of BJC. The organization is only as strong and prophetic as its constituent bodies empower it to be. Its failures are a reflection of our own. This history shows that white Baptists have too long prioritized their own conceptions and concerns of religious freedom over those of Black Baptists.

For BJC to begin to rectify and address this history, formerly Southern Baptists and American Baptists must do so as well.

Andrew Gardner

Andrew Gardner is a lecturer in religious studies and philosophy at LaGrange College. He is the author of Binkley: A Congregational History and Reimagining Zion: A History of the Alliance of Baptists.