“Nothing draws fire like drawing attention to sexual abuse and coverups in white evangelical churches. Nothing even comes close.”

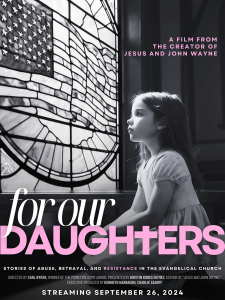

These are the words Kristin Du Mez chose to reflect on as she prepared herself on the eve of the release of her film For Our Daughters. “Those of us who do this work know what’s coming.”

Nineteen months earlier, she posted online: “I’ve noted this pattern for two-plus years now. What sickens me is that I know this is only a mild version of what survivors face in these spaces. And they don’t have platforms and often don’t have people who have their backs.”

Kristin Du Mez

That’s what For our Daughters provides. It’s an opportunity for women who have been abused by powerful men within the most influential movements of modern evangelicalism to warn the rest of the women in the country about what’s ahead for them if these men expand their power beyond the walls of their homes and churches to the government this November.

Soon after Du Mez’s bestselling book, Jesus and John Wayne, released in the summer of 2020, Du Mez began hearing from conservative evangelical women who told her: “Kristin, it’s too late for us. We’ve made our choices and we’re living our lives that we made. But we want something different for our daughters.”

As Du Mez reflected on the platform her book has given her over the past four years, she wanted to center the perspectives of women on the underside of conservative evangelicalism’s gender hierarchies. As she said recently, “This film is for their daughters and for all our daughters.”

The question those of us who watch the documentary now will have to ask ourselves is: Will we have their backs, or will we continue to perpetuate the system of sacralized male power that abused them?

Listening to the stories of women

Directed by Emmy award-winning filmmaker Carl Byker, For Our Daughters interviews women who have been victims or whistleblowers of sexual abuse in Southern Baptist churches. After the 2019 investigative report from the Houston Chronicle and San Antonio Express-News revealed more than 700 victims of sexual abuse from SBC church leaders and volunteers since 2000, awareness and calls for justice have continued to grow, despite the SBC’s lack of meaningful reform.

Jules Woodson

In addition to appearances by Du Mez, as well as a couple from her pastor, Lee Vander Zee, interviews in the film include Christa Brown (writer for BNG and author of Baptistland), Tiffany Thigpen, Jules Woodson, Rachael Denhollander (author of What Is a Girl Worth) and Cait West (author of Rift).

Hearing these women share their stories is gut wrenching. You don’t know what righteous indignation feels like until you listen to what their pastors did to them. There are moments in the film when you see them slumping over, measuring their words or looking directly into the camera with deep tears, bewilderment or rage that makes you wonder how much more you can hear.

But if you want to have their back, you have to listen. You have to listen with the empathy the men at the top of the towers of evangelical power warn us against having. And as you listen, you have to start honing your ability to recognize the theologies and arguments these men use to hurt and dismiss women.

Often in these towers, the men try to discredit women by referencing women’s hurt at the hands of abusive men. For example, Mike Winger once attempted to discredit Beth Allison Barr’s work on the history of biblical manhood and womanhood by saying it was a “story-driven theology” that is false and keeps women from reading their Bibles because they’re “emotional about it and intense about it.” He said if you have “raw edges of grief and anger and righteous indignation, you’re not going to be able to let the Bible guide and direct you here. I can’t view the world through my pain.”

But what if the pain these women feel isn’t a hindrance to their understanding of what’s happening? What if their pain is their self-awareness and attunement to what happens to women’s bodies at the hands of violent men?

The violent extremism of authoritarian Christianity

With images playing from the Stronger Men’s Conference that featured men driving monster trucks through pyrotechnics and flames while shooting fake machine guns, Du Mez notes: “Christian nationalists see themselves as entrusted with this duty to take back the country. Their plan for winning this war is for Christian men to be aggressive, militantly masculine, even violent.”

“Their plan for winning this war is for Christian men to be aggressive, militantly masculine, even violent.”

Driscoll, who was kicked off the stage at the Stronger Men’s Conference after claiming a Jezebel Spirit opened the conference when another man took off his shirt, swallowed a sword all the way down his throat and climbed a pole, is seen praying, “God, we didn’t come just to go to church. We came to go to war.”

“How do you make America great again?” Pastor Brian Gibson of HIS Church asks, “You make America Christian again.”

Worship leader Sean Feucht clarifies at the ReAwaken America tour: “We get called, ‘Well, you’re Christian nationalists! You want the kingdom to be the government!’” Then he answers, “Yes!”

Vincent James Foxx admits: “The point of Christian nationalism, my goal, is to break American democracy.”

And referring back to January 6, which he helped promote ahead of the attack on the U.S. Capitol, Pastor Greg Locke of Global Vision Bible Church in Nashville, declares: “You ain’t seen an insurrection yet. My Bible says that the church of the living God is an institution that the gates of hell shall not prevail against it. And the Bible says that we’ll take it by force.”

Protecting the status quo

As shocking as those images and words are, it makes all the sense in the world of patriarchy. This is what empires do. As New Testament scholar Mark Strauss explains in Four Portraits, One Jesus, in the Roman Empire, “Democratic values of equality and equal rights were almost nonexistent.” So of course, these men of Christian empire would want to break American democracy.

As shocking as those images and words are, it makes all the sense in the world of patriarchy. This is what empires do. As New Testament scholar Mark Strauss explains in Four Portraits, One Jesus, in the Roman Empire, “Democratic values of equality and equal rights were almost nonexistent.” So of course, these men of Christian empire would want to break American democracy.

Strauss continues: “Although people certainly had ambition, the greatest goal in life was not to climb the socioeconomic ladder but to protect the status quo. This was done by serving those above you and exercising authority over those below.”

Compare the dynamics of the Roman Empire to the testimony of the women in For Our Daughters. Cait West said: “I was raised to be a wife and a mother one day. So my whole purpose was to become this godly woman and not to serve my own needs or desires.”

Jules Woodson added: “As a girl, growing up in the church through the purity culture, what I really gained from that was that if I was this amazing Christian woman who loved the Lord and was a good person then the most I could hope for was God was going to bring me this amazing, godly Christian man.”

West later said: “Any time I showed a strong individual desire, then that was shut down. So I had to be quiet and weak just to survive.”

In other words, a woman is to have no ambition but to protect the status quo of being low while serving authoritative men.

And lest one thinks this is just the “story-driven theology” of women who are “emotional about it and intense about it” like Mike Winger accuses, you can hear the proof in the words of the men themselves.

“Godly women are designed to make the sandwiches,” pastor Doug Wilson of Christ Church in Idaho claims. “God made the world in such a way that the husband is the head, the wife is to look up to her husband, calling him, ‘Lord.’”

“I have four people in my life that I dictate the hours in their day,” declares Pastor Joel Webbon of Covenant Bible Church. “I dictate what time they go to the bathroom, when we eat, what we eat, what we wear. Those are the people that I have almost limitless authority with.”

Mainstream evangelical theology

One tempting response to the stories told in For Our Daughters is to assume these are extreme examples of a few bad apples. Brown notes how many pastors think they’re not complicit in abuse because they never abused anyone. But she counters, “They did by perpetuating this system.”

“Men think they can get away with abuse because they actually can get away with it.”

Rachael Denhollander, a lawyer and former gymnast who helped expose sexual abuse in USA Gymnastics, explains: “When you’ve created a culture where manhood and womanhood is defined by submission and authority, you have created a culture where authority goes unchecked and easily becomes abuse. And so men think they can get away with abuse because they actually can get away with it.”

The harsh reality conservative evangelicals need to realize is that the theology of authority and submission is not the worldview of a few extreme misogynists. It’s the worldview of some of their most formative and popular pastors.

Rachel Denhollander

“Authority and submission pervade the whole universe,” John MacArthur claims. “In the relationship between man and man, there is authority and submission. In the relationship with man and God, there is authority and submission. In the relationship between God and God, there is authority and submission. The entire universe is pervaded by this concept. And what is new here is not that the wife is to be subject to her husband. That isn’t new, because the Old Testament taught that. What is new is the vastness, the scope of this principle. That it absolutely pervades everything.”

John Piper says women shouldn’t be drill instructors, police officers or managers over men in the workplace because it might violate “their sense of manhood and her sense of womanhood.”

When he was called out for telling women to endure being smacked and not mentioning they should call the police, Piper clarified his position by saying women should call the police. But his reasoning was that women are to be submissive to the government as well as to their husbands. So he says a woman who does not call the police is guilty of “breaking both God’s moral law and the state’s civil law.”

So to these men, even a woman calling the police on her physically abusive husband has to be done not for the safety of the woman, but for her subjection to authority. In other words, the essence of womanhood in the world of Christian patriarchy is subjection to male power.

And what is the height of this power? MacArthur says it’s the pastorate, which he defines as “the highest location” one can “ascend to — that power in the evangelical church.”

Mainstream Republican politics

When we see the clips in For Our Daughters of pastors saying women shouldn’t have the right to vote anymore, we may be tempted to think these are the rantings of a few extremists. But when former President Donald Trump chose JD Vance as his running mate, those extremist views suddenly came to the forefront of mainstream Republican politics.

Vance’s political career has been funded by billionaire Peter Thiel, who wrote in 2009: “I no longer believe that freedom and democracy are compatible.” Thiel also added that allowing women to vote has “rendered the notion of ‘capitalist democracy’ into an oxymoron.”

But of course, Vance can’t go public with the views of the billionaire who handpicked him as his ideal politician. So instead, Vance attacks “childless cat ladies” and promotes the idea of giving more votes to people with kids. And because white evangelicals and Catholics average 2.3 children per family while atheists average 1.6 and agnostics average 1.3, the plan would effectively erase the votes of any woman who doesn’t fulfill her role of being in a man’s kitchen and on a man’s bed.

“The heart of authoritarian Christianity is identical to the heart of Republican politics.”

In the politics of Vance, the heart of authoritarian Christianity is identical to the heart of Republican politics. Kevin DeYoung wrote for The Gospel Coalition: “Here’s a culture war strategy conservative Christians should get behind: Have more children and disciple them like crazy. … There is almost nothing more counter-cultural than having more children. … The future belongs to the fecund.”

In For Our Daughters, Pastor Toby Sumpter of Kings Cross Church says of children: “They’re all arrows. But they’re all to be sharp and they’re all to do damage to the enemy. But we want our daughters to grow up seeing what they’re for.”

Then Charlie Kirk adds, “We’re just going to outbreed these people.”

What does ‘a return to who Christ really is’ mean?

One of the comments in For Our Daughters that some people may take issue with is from Denhollander, who says, “Those of us who are raising our voices are not calling for a departure from Christ, but rather a return to who Christ really is.” It’s a surprising line to hear, especially because it’s the final line of the documentary.

While the line will be comforting to Christians who watch the documentary and wonder if they can have women’s backs by speaking truth to the men leading their movement without renouncing their faith, it could be an unexpected ending for non-Christians or some survivors to hear. There are plenty of non-Christians who care deeply about these women. And some women are so hurt that they can’t imagine stepping foot inside a church again without being triggered.

Christa Brown

In her book Baptistland, Brown writes: “Perhaps it’s hard for many evangelicals to understand how something they hold so dear could possibly be so hurtful. But for me, everything connected to the faith of my childhood is a tomb of trauma. Prayer, Bible verses, hymns, God-talk, and the faith of my own heart were all perverted into weapons for sexual assault.”

So I reached out to Denhollander to ask her about the comment. She said she was answering a question about what she would tell churches who are thinking through how to respond to abuse. She’d want to assure them that in having these women’s backs, they’re not renouncing Christ but are returning to who Christ really is. She added the conversation she’d have with Christians in those settings is different than the conversations she has with the non-Christians she works with as well as with the victims she talks with.

In an interview with BNG, Du Mez added: “So personally, I agree with Rachael that Christianity as I’ve understood it does not condone this kind of power grab. But as a historian of Christianity, I’m reluctant to say, ‘This is not true Christianity.’ That’s a theological claim. As a Christian, I’m comfortable making that claim, as my pastor does in this film. But as a historian, I have to describe the systems I see in front of me that have been constructed and protected by ‘Christian’ leaders. Can that ‘Christianity’ be saved? That’s a matter of some debate, and frankly, I’m not particularly optimistic on that front. Too many have too much interest in protecting their own power. Like Christa (Brown), however, I’m certain I don’t want to see these men seize control of the country and take it upon themselves to tell all the rest of us how we should live.”

Exiles in different lands

And perhaps that’s what I found myself sitting with the most in the aftermath of watching For Our Daughters. These are men who want to use kids as arrows to damage their enemies rather than love them toward loving themselves and their neighbors. It should come as no surprise that men who think they’re entitled to such authority over women and can solve problems through violence would become violent toward women. Their theology is the sacralization of supremacy, dehumanization and violent control.

The power these men wield affects all of us in different ways. As we’ve deconstructed the towers that held us into their dark, violent world under the boot of empire, some of us have remained Christian, while others have not, and others aren’t sure what to think anymore. And even for those who have remained Christian, there is much disagreement over theology and ethics.

For those who remain Christian, there is a lot here that needs to be considered. If the most influential men shaping conservative evangelicalism think their paradigm about male authority and female submission “absolutely pervades everything,” this may require some heavy soul searching on what having a view of Christ that fosters love of self and neighbor means. It may include reconsidering such concepts as how justice is defined or how it is accomplished with or without violence against human bodies.

And as some of your assumptions begin to unravel, you may begin experiencing the exile these men threaten when questions are asked.

We’re not all going to end up in the same place. So we’re also exiled from one another in a variety of ways.

But despite whatever differences we have, there’s one thing we hopefully have in common — our love for these women. And we have an opportunity in less than six weeks to let our voices be heard. Are we going to have their backs or perpetuate the system of patriarchy by letting these misogynistic men expand their power from their homes and churches to society at large?

When you’re wondering what you should do, listen to these words from Christa Brown: “When people talk about turning the U.S. into a Christian nation, it makes me quake to ponder what that would mean for women in this country because I have seen what it means for the largest evangelical Protestant faith group in the country. And it is bloody awful.”

Rick Pidcock

Rick Pidcock is a 2004 graduate of Bob Jones University, with a bachelor of arts degree in Bible. He’s a freelance writer based in South Carolina and a former Clemons Fellow with BNG. He completed a master of arts degree in worship from Northern Seminary. He is a stay-at-home father of five children and produces music under the artist name Provoke Wonder. Follow his blog at www.rickpidcock.com.

Related articles:

Steve Lawson preached fire and brimstone except for himself | Analysis by Rick Pidcock

Church life is the perfect cover for abusers, Brown says in BNG webinar

Jesus and John Wayne exposes militant masculinity in the age of Trump | Analysis by Alan Bean