It’s back to school time and, in the latest effort of book banning, new state legislation will restrict literature allowed in Texas schools based on a vague rating system about sexual content.

House Bill 900, which goes into effect Sept. 1, completely bans books that are “sexually explicit” and restricts books that are “sexually relevant” by requiring parental approval before a student can access the literature.

Bookstores and publishers are required to analyze and rate any book sold to school libraries to determine if “the material describes, depicts or portrays sexual conduct in a way that is patently offensive.” Not only are they required to rate any future sales to school districts, but booksellers also must retroactively provide ratings for any books sold in the past that are still active in schools and “issue recalls” on “patently offensive” books.

The bill’s definition of what “patently offensive” means is ambiguous at best. One incredibly subjective criterion is “whether a reasonable person would find that the material intentionally panders to, titillates or shocks the reader.”

The bill’s definition of what “patently offensive” means is ambiguous at best. One incredibly subjective criterion is “whether a reasonable person would find that the material intentionally panders to, titillates or shocks the reader.”

HB 900 requires booksellers to report their ratings to the Texas Education Agency for review. After reviewing the ratings, TEA will make any corrections it sees fit and require bookstores to change their evaluations accordingly. A bookstore that refuses to change its ratings or fails to report ratings to TEA will be prohibited from selling any books to any public school in a Texas school district.

Due to its vague language and punishment system, this bill is expected to have widespread negative effects on school libraries and bookstores, resulting in children’s limited access to new literature this coming school year and the attempted erasure of many minority voices present in children and young adult books.

In response to HB 900, two Texan bookstores along with a few bookseller associations filed a complaint challenging the bill. They claim the rating criteria are vague and subjective, that the law requires unnecessarily burdensome and costly work for bookstores and that ultimately such a law violates students’ first and 14th amendment rights.

Long history of censorship

HB 900 is the most recent in a long history of book censorship in this country.

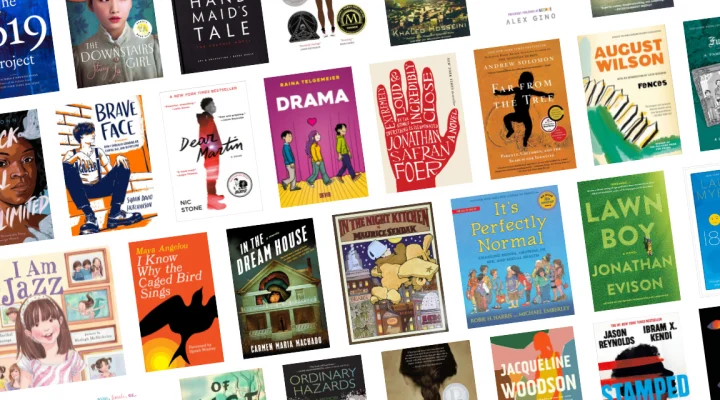

According to PEN America, a nonprofit that advocates for free expression in various forms of writing, public schools have seen an uptick of book banning in the past three years. From July 2021 to June 2022, 1,648 books were banned, affecting more than 5,000 schools and 4 million students within these districts.

“Restricted access to literature is a rapidly popularizing hot button political issue.”

The modern push for book banning originated from a few groups who are a vocal minority. Even though 70% of parents oppose book bans, restricted access to literature is a rapidly popularizing hot button political issue. In recent years, this argument has shifted from the school level to a larger governmental level, and as a result, book banning is beginning to become more mainstream as a political movement.

With bans, it’s important to notice whose voices are most often being silenced. Many bans, like HB 900, focus on censoring books with “sexual” content. However, sexually explicit content does not necessarily mean inappropriate mentions of sexual experiences between characters, it’s often code for books containing LGBTQ characters.

In 2021, the rise in book bans largely centered around Critical Race Theory controversies, resulting in the ban of many books written by people of color and books about characters of color. In 2022, book banners also focused on restricting literature by and about LGBTQ individuals.

The majority of banned books are by or about people of color and LGBTQ people. Between January and June 2022, PEN America found “30% of the unique titles banned are books about race, racism or feature characters of color. Meanwhile, 26% of unique titles banned have LGBTQ characters or themes.”

“The majority of banned books are by or about people of color and LGBTQ people.”

This indicates an attempted erasure of certain voices who already are largely underrepresented in literature. It deprives some children the ability to see themselves in the books they are allowed to read, and it denies other children the ability to step outside their own identities and into greater understanding and empathy of diverse perspectives.

What’s ‘obscene’?

As many book bans target queer-themed books and literature on sex education, there has been a loosening understanding on what qualifies as pornographic or obscene. The word “obscene” actually carries legal weight in that obscenity is not protected under the First Amendment and therefore should not be in schools or anywhere else. The legal evaluation of obscenity requires materials fail a specific tripartite test. However, book banners are flippantly labeling literature as “obscene” simply because they do not agree with its content.

We all can agree sexually explicit content absolutely does not belong in the hands of a child. But when these terms are left undefined, they are too easy to abuse in order to apply them simply to a group of people you don’t like. The common “you know it when you see it” definition is unhelpful in this conversation because some people are defining pornography as a book with any two queer characters in it.

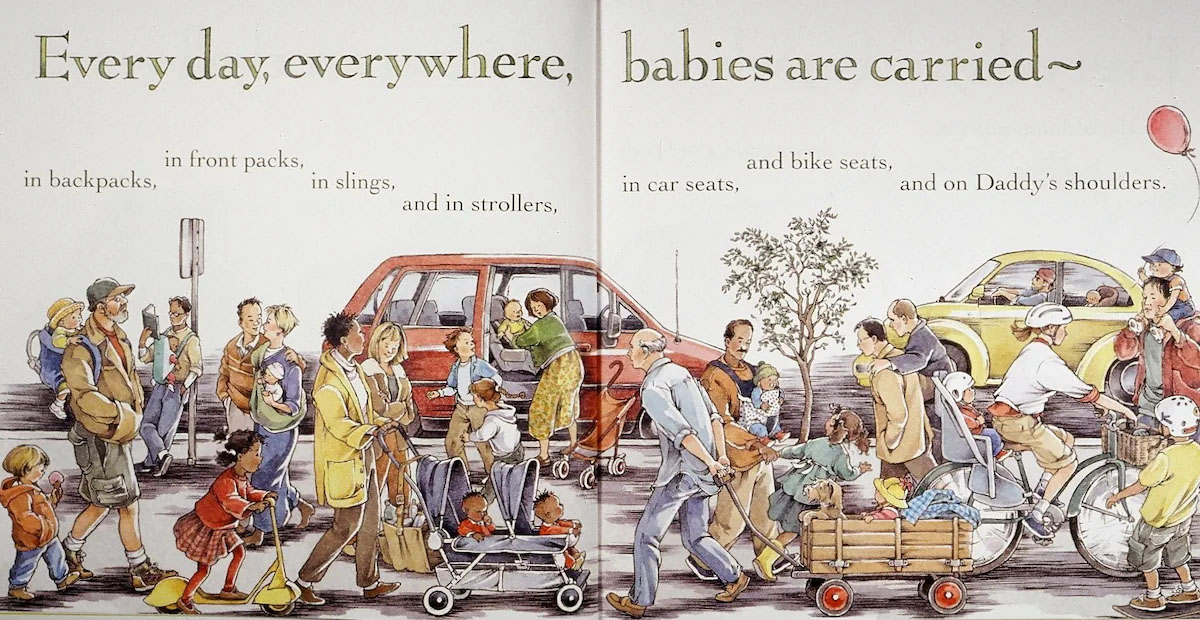

A spread in the book “Everywhere Babies,” by Susan Meyers and illustrated by Marla Frazee. (Marla Frazee)

For example, a picture book called Everywhere Babies was banned in Florida last year. In the book, there’s one page with a lot of images of babies being carried in slings, strollers, backpacks, wagons and more on a crowded street. On the street are two fully clothed men walking next to each other with one man’s arm over the other man’s shoulder, depicting two men who might possibly be a couple. The book was banned for being “pornographic.”

The idea that any literature with LGBTQ themes or characters are inherently pornographic or sexual simply isn’t true. Such a belief perpetuates the harmful stereotype that queer people are naturally more promiscuous, which is a way heterosexual, cisgendered groups attempt to “other” the LGBTQ community. It creates fear, distrust and distaste of LGBTQ people and leads to homophobia.

Journalist Katy Waldman compares book bans to a “fig leaf.” She writes, “What parents and advocacy groups are challenging in these books is difference itself. In their vision of childhood — a green, sweet-smelling land invented by Victorians and untouched by violence, or discrimination, or death — white, straight and cisgender characters are G-rated. All other characters, meanwhile, come with warning labels. When childhood is racialized, cisgendered and de-queered, insisting on ‘age-appropriate material’ becomes a way to instill doctrine and foreclose options for some readers, and to evict other readers from childhood entirely.”

“Book banning is an attempt to literally and figuratively whitewash childhood.”

Book banning is an attempt to literally and figuratively whitewash childhood, and it teaches children who is allowed to be a protagonist and who is not. Who deserves to have a story and who does not.

Real life

Beyond an attempt to erase identity, book bans also target stories with difficult life moments.

Last year, 38% of banned books covered topics on health and well-being for students and 30% covered grief and death, according to PEN America. These include books with “content on mental health, bullying, suicide, substance abuse, as well as books that discuss sexual well-being and puberty … books that have a character death or a related death that is impactful to the plot or a character’s emotional arc.”

Let’s be clear. Banning books from children does not ban children from being exposed to the kinds of concepts within banned books. Suicide, puberty, queer people, violence, mental health struggles, substance abuse and racial trauma and inequality all still exist in the world. Try as they might, book banners cannot make queer people disappear just because literature with queer characters is deemed “sexually explicit.”

For many children and students, the topics and identities found in these banned books are not ones they can avoid. Why not give them as many tools as possible to face it? And why not help future generations grow up with pride for their personal identities and empathy and love for those who are different from them?

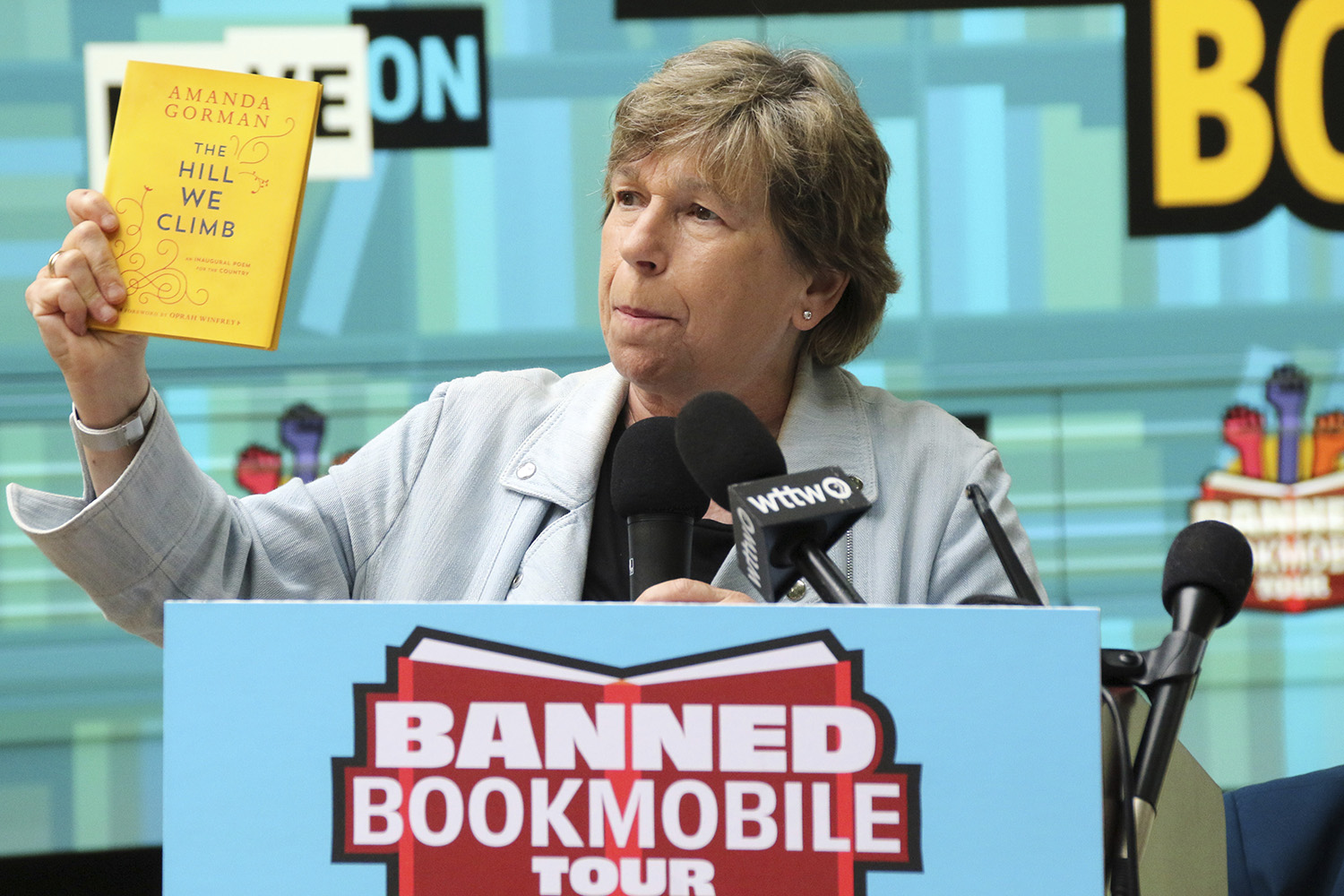

AFT President Randi Weingarten holds up Amanda Gorman’s banned book as she speaks to the crowd during the MoveOn political Action’s “Banned Bookmobile” as it makes its first stop on its multistate tour at Sandmeyer’s Bookstore in Printers Row, Chicago on July 13, 2023. (Photo By: Alexandra Buxbaum/Sipa USA)(Sipa via AP Images)

Intentional confusion

One of the biggest concerns with book bans is how vague language leads schools and booksellers to remove all types of books out of a confusion about the nebulous governmental standards and fear of punishment for not complying with bans.

In response to vague legislation on book censorship, schools in recent years have erred on the side of caution and removed any questionable books. As a result, there is a rising trend in “wholesale bans” where entire classrooms or entire libraries are emptied of all books or shut down altogether.

The danger in vague language is that it creates confusion and intimidation which leads to the removal of more literature than necessary for fear of punishment and for lack of time and capacity to decipher unclear criteria.

As a result of HB 900, several schools are simply not buying new books for the 2023 school year. These kinds of laws not only restrict children’s access to some books, they often result in an unavailability of all new literature or all literature in general.

Fighting against this outcome, the complaint against HB 900 points out that, “Legislators expressed concern that the overbroad language of the Book Ban could result in the banning or restricting of access to many classic works of literature, such as Twelfth Night, A Midsummer Night’s Dream, Romeo and Juliet, Of Mice and Men, Ulysses, Jane Eyre, Maus, Anne Frank’s Diary: The Graphic Adaptation, The Canterbury Tales, I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings, and even the Bible.”

Even the Bible — talk about a book full of sexually explicit content.

(Karl Aspelin, Public Domain, Wikimedia Commons)

Christians to the front once again

Despite holding such a scandalous book as their sacred text, Christians are the ones leading the charge in book banning for religiously founded moral reasons, and some of the most vocal groups have been connected to Christian nationalism.

While Christians banning books has seen an uptick in recent years, it is not merely a modern phenomenon.

According to National Geographic, “Most of the earliest book bans were spurred by religious leaders, and by the time Great Britain founded its colonies in America, it had a longstanding history of book censorship.”

The first instance of book banning in what would later become the United States occurred in 1650 when colonist William Pynchon published a pamphlet called the Meritorious Price of Redemption, which claimed anyone who followed God and Christian teachings would go to heaven.

This message upset a group of Puritans who believed in a more selective system that allowed only predestined people in heaven. In response, they burned and banned Pynchon’s pamphlet.

“Today’s bans are only the most recent in a long line of religiously founded censorship.”

Later, Christians opposed and banned various anti-slavery texts, books referencing birth control and literature on interracial marriage. Today’s bans are only the most recent in a long line of religiously founded censorship that simply disagrees with the content of a book or the identity of its writer.

Is this what’s most important?

Surely banning children’s books should not be the focus of Christians in this country. When looking at all the problems in the world right now, or even just the most needed reforms in public schools in the United States, banning queer authors and authors of color hardly seems like it should be at the top of the list.

I once had a landlord who was endearing but terrible at his job. He was the kind of landlord who painted over hinges, light switches and even window sill debris just to cover it up. He would sometimes bring his small children to shovel snow from our walkway and often would ask to use our things, like towels, spoons or hair ties to fix something broken around the apartment.

I once had a landlord who was endearing but terrible at his job. He was the kind of landlord who painted over hinges, light switches and even window sill debris just to cover it up. He would sometimes bring his small children to shovel snow from our walkway and often would ask to use our things, like towels, spoons or hair ties to fix something broken around the apartment.

One time when we requested maintenance on our poorly working heat, he came over and became fixated on painting the baseboards of one room and completely neglected to fix the heat. Even though the overall paint job was terrible in the apartment (he’d once brought his grade school kids with him to help paint, and they mostly painted the hardwood floor), he was fixated on that baseboard and spent an hour painting one corner, not leaving enough time to properly fix the heat.

Reading HB 900, I couldn’t help think about this landlord. A hyper fixation on library censorship is hardly the most needed reformation of public schools. Surely we should attend to the heat first.

Attend to the declining statistics of reading comprehension and math scores in the wake of the pandemic, the rising statistics of kids struggling with mental health problems at younger and younger ages, the fact that the youngest generations will be forced to deal with climate change in a way that none of us have or the growing problem of gun violence in our schools.

“I’m exhausted by a government that prioritizes the restriction of books in our schools over the restriction of guns in our schools.”

I’m exhausted by a government that prioritizes the restriction of books in our schools over the restriction of guns in our schools. To put it mildly, a claim that such a ban was created to protect children is simply disingenuous.

Rudine Sims Bishop, a professor known as the “mother of multicultural children’s literature,” wrote in 1990 about the concept of books being mirrors and windows. Children, and all of us, desperately need books that are mirrors which reflect their own identities and life experiences in characters and plots. We also need books that are windows to show us a world, an identity, an experience different than our own.

Bishop writes that books “won’t take the homeless off our streets; it won’t feed the starving of the world; it won’t stop people from attacking each other because of racial differences; it won’t stamp out the scrouge of drugs. It could, however, help us to understand each other better by helping to change our attitudes toward difference. When there are enough books available that can act as both mirrors and windows for all our children, they will see that we can celebrate both our differences and our similarities, because together they are what make us all human.”

It’s true that not all the problems in public schools can be solved by reading more books, but it doesn’t seem like a bad place to start.

Reading feeds the imagination of a child, opening up the world with its joys and struggles into unending possibilities. Children and adults discover themselves in books and peer into what it might be like to be someone else. They learn examples of how to treat one another, how to process some of life’s hardest moments and how to think critically about a complicated topic.

“All children need and deserve to see themselves in books.”

All children need and deserve to see themselves in books, regardless of race, gender, sexual orientation, socioeconomic group or birthplace. And what better way to make a more peaceful future than to teach children at a young age not only who they are and can be, but also what it’s like to be someone else and why that someone else deserves love and respect too.

There was no queer literature in my school library growing up. And there were very few stories written by authors of color that weren’t token books about civil rights in my library either. I bet many of you had similar experiences in your public schools growing up.

Diversity is not new. But representation and the ability to discuss difference is newly growing and the backlash has been harsh. It’s impossible to read or watch the news without multiple mentions of how much discord there is in society.

There are a lot of reasons why our country is so divided and why hate seems so palpably on the rise. But racism and homophobia are taught behaviors, and I can’t help but wonder if books could teach the next generation a different story.

Laura Ellis

Laura Ellis leads a collaborative effort between BNG and Baptist Women in Ministry to increase female voices in our opinion content. She is a former Clemons Fellow with BNG and earned a master of divinity degree from Boston University School of Theology. She lives in Waco, Texas.

Related articles:

Everything you need to know about the rise in efforts to ban books from libraries | Analysis by Mark Wingfield

What a first grader learned about book-banning from an old-timey Baptist preacher | Opinion by Marv Knox

That time I went to the school board meeting to speak against banning books | Opinion by Mark Wingfield