We are children of God. This statement is incredibly simple. And incredibly radical.

In Genesis, God creates humanity out of God’s image. Humans are made into God’s image and grow into God’s likeness. We are like God; we bear God’s fingerprints. Jeremiah describes God as the potter and humanity as the clay, shaped carefully by God’s hand. In First John, we see the author in awe of God’s goodness, exclaiming, “See what great love (God) has lavished on us, that we should be called children of God!”

This is more than a simple affirmation or doctrine.

This is more than a simple affirmation or doctrine.

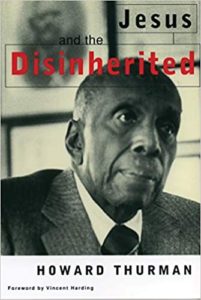

Howard Thurman, a Black pastor, professor and mystic, explains how knowing yourself to be a child of God can radically change your view of yourself and how you look at life. Thurman lived in an era where segregation was legal. He was only two generations separated from enslavement. Martin Luther King Jr. is said to have carried Thurman’s seminal work, Jesus and the Disinherited, as he traveled. In that text Thurman gives an account of his grandmother, an enslaved woman who would attend secret worship services led by an enslaved preacher. He describes his excitement when his grandmother recalled those sermons. The enslaved minister frequently made the climactic point: “You are not slaves. You are God’s children.”

This, Thurman said, “established for them the ground of personal dignity, so that a profound sense of personal worth could absorb the fear reaction. This alone is not enough, but without it, nothing else is of value.”

Thurman explains that a person’s conviction that she or he is God’s child “automatically tends to shift the basis of his relationship” with others. The Christian then “recognizes at once” that to fear another “is a basic denial of the integrity of his very life.” For Thurman, denying one’s own imago dei, or image of God, could be considered worse than the threat of death.

Thurman explains that a person’s conviction that she or he is God’s child “automatically tends to shift the basis of his relationship” with others. The Christian then “recognizes at once” that to fear another “is a basic denial of the integrity of his very life.” For Thurman, denying one’s own imago dei, or image of God, could be considered worse than the threat of death.

Why is this so profound? Four reasons come to mind:

First, one’s recognition as a child of God is the impetus for resistance to injustice. Knowing who I am, and where my identity is rooted, frees me to be fully myself and resist anyone who denies that reality.

Second, knowing myself as a child of God enables me to speak truth, though my voice may waver and legs may shake. As someone who often has preferred niceties over truth-telling and placation of others’ feelings over the Holy Spirit’s direction, speaking the truth often comes with hesitation and nervousness.

I remember delivering a paper utilizing Martin Luther King Jr.’s critique of white moderates in his Letter from a Birmingham Jail and applying it to moderate Baptists in a moderate Baptist institution. My voice shook as I upheld the example of Colin Kaepernick in a room full of white people. I had once claimed the moniker “moderate” and had been proud to do so. But as I read Scripture, the witness of African Americans and listened to the Holy Spirit, I realized I had to abandon the tenants that upheld “moderate” in my context today. Rather, following King, I had to become a radical for love.

For me, to be moderate was to uphold the status quo, to return to a time of false peace. My truth-telling did not have the grave consequences that Kaepernick or King faced, and, as I’ve continued to attempt to tell the truth, my voice wavers less and less.

Third, knowing myself as a child of God allows me to take risks that could lead me to harm from others who want to deny that reality. I saw that in Martin Luther King, whose focus on systemic poverty, workers’ rights, and civil rights led to his execution. The images of Black men holding signs that say, “I am a Man” during the sanitation strike in Memphis, where King was murdered, feels woefully resonant with Black people caring signs saying, “Black Lives Matter” today.

More recently, I saw such risk-taking in June Joplin, whose insistence that she is a child of God as a trans woman led to her termination at her church. Nonetheless, Joplin fiercely declares: “God is always up to something. That’s good news. And there’s more; God is constantly inviting us to be a part of that something.”

Where might our identity as children of God prompt us to take risks? Where is affirming ours, and others’ belovedness more important than job security, than death?

Fourth, knowing myself to be a child of God compels me to see all others as God’s children. Even, and especially, others who make me uncomfortable or whose voices I haven’t heard. Thurman remarks: “The masses … live with their backs constantly against the wall. They are the poor, the disinherited, the dispossessed. What does our religion say to them?” Does our faith in the incarnate Christ, whose Spirit lives within and among us, speak good news to the dispossessed? How does knowing others to be children of God affect how we live, how we love, how we vote?

I am a child of God. You are a child of God. Now, to live out that reality.

Kate Hanch serves as associate pastor for youth and families at First St. Charles United Methodist Church in Missouri. She earned a master of divinity degree from Central Baptist Theological Seminary and a Ph.D. in theology and ethics from Garrett-Evangelical Theological Seminary. She is ordained in the Cooperative Baptist Fellowship and lives in O’Fallon, Mo., with her husband, Steve.