I consider myself fortunate to have come of age in the 1960s and to have been educated at Southern Baptist Theological Seminary in the early 1970s. None of us has much control over the time in which we live. Although we exercise some influence over the places we go, the people who come into our lives are gifts.

So it is with sermons, too, I would argue. We stumble into them, and unknown to us at the time, their impact can be lasting.

As I look back over those formative years during a decade of education and great social change, there are four sermons that stand the test of memory and influence over time. I am a different, and better, person for having heard these four ministers preach the word.

Those years were permeated by conflict and change, but the feel was different than what I experience today. I’m sure my youth in one case and advancing years in the other make a difference. My hunch is, though, that preaching today still has the potential for leading us from where we are to where we need to be. These sermons helped nudge me in the right direction.

Clarence Jordan

The first was preached by Clarence Jordan in 1968, I believe. The setting was the chapel at Southeastern Baptist Theological Seminary in Wake Forest, N.C., and the occasion was a missions conference sponsored by the Baptist Student Union of North Carolina.

Clarence Jordan

I had met Jordan a year or so earlier when he served on a panel at another BSU conference alongside a public information officer from Fort Bragg. The subject was the Vietnam War, and I had asked Jordan, in front of several hundred people, how he could justify not supporting the war effort. He said, “I just read the New Testament and try to do what it says.”

Embarrassed, with no good response to that, I took my seat.

In the later chapel message, he preached a sermon about the adventures of three students in a fiery furnace. (It was later published in a book of sermons.) The point, as you might suspect, was that the fate of Daniel and his friends was comparable to that of students in the ’60s who resisted the Vietnam War from a sense of doing what God commanded.

It was a simple message, but one that hit me full force, like his answer to my earlier question. As the sermon ended, he told the story of a student who had been arrested for refusing to register for the draft. The judge had released him on probation with the condition that he not participate in any peace demonstrations. After reflecting on the conditions of his probation, he felt he could not abide by the terms, and he joined a demonstration. When standing before the judge a second time for resentencing, he read a statement.

At that point in the story, Jordan reached in his coat pocket and took out a folded piece of paper. He then read the statement the student made to the judge. It was an eloquent summary of his attempts to live by the terms of the probation but finally deciding his conscience would not let him be still while the war continued. Knowing it would put him in conflict with the law again, he decided he must do that anyhow. After reading the statement, Jordan folded up the piece of paper, put it in his pocket, and sat down.

It was several minutes before anyone moved or made a sound. The quiet was deafening. The message was clear. I can remember it as if it were yesterday.

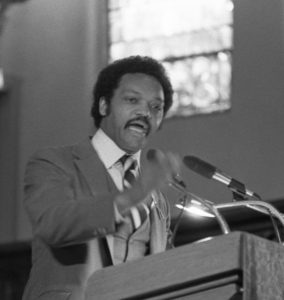

Jesse Jackson

The second sermon that had such an effect I heard in 1969. It was preached in an African American church in Indianapolis. That summer, I was working as a research assistant for Jim Greene, BSU director for North Carolina. We were surveying the inner city regarding health care delivery. Our “office” was in a building across the street from the church, which we shared with the Black Panther breakfast for kids program.

Jesse Jackson preaches at Shiloh Baptist Church, Washington D.C., May 3, 1983. (Photo by Joseph Klipple/Getty Images)

Word came that Jesse Jackson was coming to town to lead a march to protest racism and poverty. The march was on Sunday with a rally the night before at the church. The members of our group decided to go to the rally. The church was packed that night. Jim and I were about the only white faces in the crowd, and we sat near the back.

Jackson was preaching on Ezekiel and the dry bones. He had brought with him the Operation Breadbasket choir and orchestra from Chicago. There must have been close to a hundred singers and musicians in matching blue jeans. A small child who was a lead singer had to sit on a stool to reach the microphone.

As the sermon built to a climax, Jackson and the band leader worked in sync with each other. He quietly started with the foot bone connected to the heel bone. As he moved up the skeleton, the musicians quietly modulated the chords to higher notes. Each step got a little higher and a little louder. By the time he got to the head bone, the entire place had erupted. Everyone stood and clapped to the music.

Jim and I did our best to move like everyone else, but I’m sure we stood out in spite of that. Because the crowd was moving as one to the beat, I had real fears the floor would give way and we would fall into the basement. The music was deafening. The message was clear. I can remember as if it were yesterday.

The next day, a Sunday, Jackson led a march to the governor’s mansion. Many of us in the audience went with him to register our protests of the poverty we were measuring in our survey of the health of inner city residents.

John Claypool

John Claypool

The third sermon was delivered at Crescent Hill Baptist Church in 1970. It, too, was published in a book of sermons. The title was, “Life is Gift.” It was preached by John Claypool, my pastor at Crescent Hill.

The sermon was a reflection of what he had learned through the dark season of grief he had experienced after the death of his young daughter from cancer. His conclusion was that all life, even that which is shortened prematurely, is a gift from God. We do not call ourselves into being. We are surprised to find ourselves alive on the earth. We cannot claim to be entitled to life of a certain length or station. All we can do is be thankful for whatever time we are allowed for walking, talking and enjoying the company of others.

That recognition does not diminish the sadness and grief we experience when we realize our own demise is certain or when we experience the loss of someone dear to us. It can, however, allow us to move through the seasons of grief more thoughtfully and to arrive at a better place after a setback or a loss. Gratitude can have a healing influence on almost any situation, not least one of great anguish.

Claypool was always able to end his sermons with a pause or a question that left us grateful for the insight his sermons brought us. His quiet, measured style of preaching and the example of his life were reasons that 11 a.m. on Sundays were the highlights of the lives of many of his congregants at Crescent Hill Baptist Church.

Grady Nutt

The fourth sermon had a lasting effect, as well. I do not remember the exact date or occasion, but it had to be the late sixties or early seventies. Grady Nutt was the preacher. Although he was not a pastor for much of his career, he was a wonderful preacher. He was never at a loss for words, and most of the time they were funny. Even his comedy routines were often sermons in disguise.

Grady Nutt

The sermon I remember best is his telling of the story of the followers of Jesus on the Road to Emmaus after the resurrection. Grady’s storytelling abilities were legendary. As you can imagine, the build up of the conversation between the followers was full of suspense. It may have lasted longer and had more details than the original conversation. Jesus joins them, and the secret the audience knows, but the followers don’t, heightens the suspense. Then, finally, they stop, Jesus breaks the bread, and the secret is out.

I can hear in my mind the voice of Grady telling us how the news of the resurrection changed the lives of those who had the experience of the risen Jesus. All these years later it is not hard to recover the emotion of celebration we all experienced in the audience that day. Great preaching does that to you.

Although these sermons were separated by time, distance and theme, they all had the characteristics of good preaching. They also were placed in my life at important junctures of my faith journey. I am grateful for the influence each of them had on my spiritual formation. I only hope I can live up to the truths to which each was a witness.

Stuart R. Sprague is emeritus professor of religion and philosophy at Anderson University and held clinical appointment as associate professor of family medicine at the Medical University of South Carolina. He earned a bachelor of science degree in chemistry from Duke University and a master of divinity and Ph.D. from Southern Baptist Theological Seminary in Louisville, Ky. He and his wife, Sarah, are active members of Boulevard Baptist Church in Anderson, S.C., where he participates in a Community Remembrance Project in conjunction with Equal Justice Initiative.