But to preach the gospel is not just to tell the truth but to tell the truth in love and to tell the truth in love means to tell it with concern not only for the truth that is being told but with concern also for the people it is being told to.

Frederick Buechner wrote those words for the Lyman Beecher Lectures at Yale Divinity School in 1976. A year later, they became the book, Telling the Truth, the Gospel as Tragedy, Comedy and Fairy Tale.

Bill Leonard

A faculty colleague at the Baptist seminary in Louisville told me in 1979, “You have to read this book!” By page 8, on which the above words appeared, I was hooked. Still am. I’ve not done a tally, but my guess is that other than Jesus, I’ve quoted Frederick Buechner in my sermons more than anyone else.

Buechner died Aug. 15 at age 96. Since then, a wonderful collection of reminiscences has appeared in multiple venues, including superb essays by my great friends Brett Younger, Andrew Daugherty and Steve Shoemaker published on BNG. So just for the grace of it, as Buechner might say, I went back to Telling the Truth and there it was again: “God is the comic shepherd who gets more of a kick out of that one lost sheep once he finds it again than out of the ninety and nine who had the good sense not to get lost in the first place. God is the eccentric host who, when the country club crowd all turn out to have other things more important to do than come live it up with him, goes out into the skid rows and soup kitchens and charity wards and brings home a freak show.”

That oh-so-Buechnerian passage got stuck in my head (and heart) so deeply that a decade or so ago, when preaching at an oh-so-respectable Baptist church hereabouts, I got all Holy Ghost and blurted out, “Should the ‘rapture’ occur any time soon, I’m not going. Instead, I’m going to hold on to a tree or another sinner, and stay right here with Jesus, until the last, lost sheep comes home.”

On their way out the door, several committed premillennialists took me to task for the eschatological heresy of my sermon. I started to blame Jesus and Buechner but held my peace. On my way to the parking lot, a gangly teenager accosted me, commenting, “I heard what you said about that ‘rapture,’ and I decided that, if it happens, I’d like to stay here with you and Jesus, too.”

“That Sunday, for one brief, shining moment, Jesus and Buechner carried that kid and me into the grand gospel freak show.”

That Sunday, for one brief, shining moment, Jesus and Buechner carried that kid and me into the grand gospel freak show.

In the spring of 2000, Buechner preached at baccalaureate and received an honorary doctor of humane letters degree from Wake Forest University. He was nominated for the award by none other than poet, writer, dancer, Wake Forest professor of humanities, the irrepressible Maya Angelou, who also invited Buechner to stay at her home, an invitation that sealed the deal.

He came and, since his wife was unable to attend, brought one of his best friends. I was privileged to drive Buechner to various events, including a dinner the university president, Thomas Hearn, gave for the honorary degree recipients. I arrived at Maya Angelou’s house and her assistant invited me in, taking me to the back yard where she was hosting the two men in a gazebo. They were chatting, over what my blessed WFU colleague James Dunn called “light libations.”

On the way to the dinner, Buechner told me Maya Angelou had given him yet another gift. She explained that while her large library of books was housed on the first floor of her home, she kept another library on the second floor, limited only to African American authors — except for the books of Frederick Buechner!

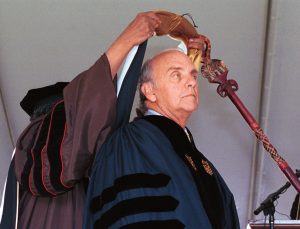

Maya Angelou hoods Frederick Buechner at the Wake Forest University commencement ceremonies, May 2000. (Photo by Ken Bennett)

Professor Angelou hooded him at graduation, but I’ve always suspected that having his books in her second-floor library was, for Buechner, an even greater honor.

As it happened, by luck or grace, as Buechner might say, I nominated Helen Lewis, “the mother of Appalachian studies,” for an honorary doctor of divinity degree that same year. Helen, social activist, scholar and teacher, helped start the Appalachian Ministries Educational Resource Center based in Berea, Ky. She and I became friends when, in 1988, I joined the summer faculty of a month-long AMERC course on Appalachian religion, conducted on the campus of Berea College.

A fierce defender of the rights of Appalachian women and men, Helen participated in, and was sometimes arrested in, a variety of public protests aimed at addressing social inequities. She joined the infamous 1989 Pittston Miner’s Strike at a coal mine in Virginia. A Primitive Baptist preacher would drive protesters to the mine in his church bus; they would get arrested for trespassing, post bond and the Primitive Baptist preacher would pick them up at the jail. That summer, we thought we might have to raise bail money for Helen so she could teach in the AMERC program. We didn’t, but we would have.

A 2012 collection of Helen’s writings titled Helen Matthews Lewis, Living Social Justice in Appalachia, edited by Patricia Beaver and Judith Jennings, documents her activism as community organizer, professor, social critic and Appalachian prophet. In that volume, Helen recounts her conversion in a required chapel service at her alma mater, Bessie Tift College in Forsyth, Ga., where she was a classmate of Flannery O’Connor.

The year was 1941 or ’42, and the preacher was Clarence Jordan, who, Helen recalled, “had just finished going to Baptist seminary and was starting this interracial farm in rural Georgia called Koinonia. And he tells us about it, what he’s going to do, and he retold the story of the Good Samaritan, only it was his Cotton Patch version. This man is going down the road and gets beat up by thieves and is left bloody on the side of the road.” A preacher and a “choir leader” pass by but are too busy to stop “and finally this old Black man, he’s riding down the road in his wagon, and sees him, and he takes him down to town and tries to put him in the hospital, and they won’t let him in because this Black man brought him in. So he takes him down into ‘n—town’ where there’s no lights and there’s no pavement and there’s holes in the road, you know. And he’s the Good Samaritan.”

Then Helen Lewis commented: “I’m sitting there listening to this man, and it’s kind of like, ‘My God that is it, that is it!’ And there’s no going back after that. I mean it just turned my mind. From then on.”

Now in her late 90s, Helen Lewis never has gone back on what she heard, internalized and acted on in the words of Clarence Jordan.

And there’s Maya Angelou, whom I’ve also quoted frequently in sermons, particularly this: “When someone says to me, ‘I’m a Christian,’ I ask, ‘Already?’”

That graduation in May 2000 brought together Buechner, Angelou and Lewis, a trinity of truth-tellers. In a country (and a church) riven by “alternative facts,” we need to keep remembering and reading them, “not just to tell the truth, but to tell the truth in love.”

Bill Leonard is founding dean and the James and Marilyn Dunn professor of Baptist studies and church history emeritus at Wake Forest University School of Divinity in Winston-Salem, N.C. He is the author or editor of 25 books. A native Texan, he lives in Winston-Salem with his wife, Candyce, and their daughter, Stephanie.

Related articles:

Frederick Buechner influenced millions with his insightful writing and quotable lines

On the anniversary of 9/11: Reclaiming ‘unanticipated courage’ | Opinion by Bill Leonard