Stopping into one of the dollar stores this week, I couldn’t help but notice the display of reduced Easter memorabilia prominently arranged on a counter near the front doors. Alongside the plush toy bunnies, brightly colored plastic eggs, assorted dye kits and baskets lined with artificial grass were two items that stopped me in my tracks: candy crosses.

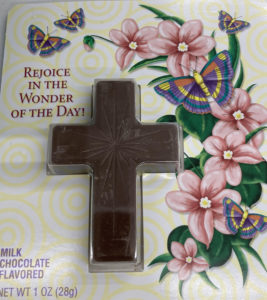

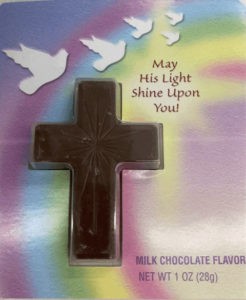

One expressed the hopeful message, “May His light shine upon you! Milk Chocolate Flavored, Net WT 1 Oz (28g),” while the other admonished, “Rejoice in the Wonder of the Day! Milk Chocolate Flavored, Net WT 1 Oz (28g).”

One expressed the hopeful message, “May His light shine upon you! Milk Chocolate Flavored, Net WT 1 Oz (28g),” while the other admonished, “Rejoice in the Wonder of the Day! Milk Chocolate Flavored, Net WT 1 Oz (28g).”

Is this now the summation of the death of Jesus — and of the cruel instrument of torture and execution on which he suffered? Are our marketing motivations in this “Christian nation” so strong that something this sacred is thus diminished and demeaned? Has the Cross of Christ really been reduced to a chocolate treat in a discount store?

When I was younger, I heard misguided criticisms of my Catholic brothers and sisters in the faith. That was years ago when many Baptists wondered if Roman Catholics were Christians at all. “Catholics focus too much on Good Friday, and in their churches, Jesus is still on the Cross,” someone would say, referring to a beautifully carved crucifix. “But Jesus isn’t there. The Cross is empty because Jesus is alive!”

But as I held in my hand what was once a focus of our faith and a symbol of suffering, now reduced to a sweet confection, I longed for a more thoughtful remembrance of Jesus’ final hours. Of course, I am not arguing for candy crucifixes, with milk chocolate figures of Jesus hanging on edible crosses. Instead, I would like for the “wonder of the day” not to be served up in 28-gram portions.

In an Easter special issue in 2015, Newsweek magazine examined the terrifying nature of the Cross and its purpose as a political tool of the Roman Empire: “In the age of Roman domination, only Rome crucified. And they did it often… . It was a popular method of dispatching threats to the empire. ‘Romans practiced both random and intentional violence against populations they had conquered, killing tens of thousands by crucifixion,’ says New Testament scholar Hal Taussig” of New York’s Union Theological Seminary.

Over time, after trying other vicious methods of capital punishment, the Romans realized that crucifying its state enemies was the greatest deterrent to rebellion and insurrection. The agonizing death of victims of crucifixion, as well as the punitive custom of leaving bodies on crosses to be picked apart by scavenger animals and birds, was absolutely shocking. Every aspect of death on a cross was a ghastly reminder of imperial power.

“Every aspect of death on a cross was a ghastly reminder of imperial power.”

But the horror has been hidden in our contemporary gospel choruses. In typical fashion, the lyrics of “Mighty Cross,” by Elevation Worship, move rather quickly to focus on our forgiveness purchased through Jesus’ death, as well as to gloss over the understandable panic that caused him to beg God for a different plan:

On the day that death surrendered to the mighty Cross of Jesus Christ,

The earth would shake, beneath the weight of darkened skies.

On his brow, a crown of sorrow for a King whose weakness was our strength.

No word he spoke, his love was shown for all to see.

Oh, the Cross of Jesus Christ, he’s the reason I’m alive.

For his blood has set me free. It will never lose its power for me!

But if one is not convinced by the theory of substitutionary atonement, then the rush past Jesus’ pain to our personal rescue is inappropriate. Suppose, for example, that other ancient meanings of the Cross which have been offered over the course of church history are considered.

Perhaps one is moved by the martyr motif that acknowledges Jesus as “the faithful witness (martus) … who loves us and has freed us from our sins by his blood” (Revelation 1:5-6). Or maybe one is emboldened by the exemplar, or moral example, theory of the cross, where Jesus demonstrates, in his own suffering, that “no one has greater love than this, to lay down one’s life for one’s friends” (John 15:13).

In either case, the follower of Christ must contemplate the figure who was on the Cross for six excruciating hours. For he was either the ultimate witness, or martyr, testifying through his suffering to the power in weakness and vulnerability. Or he was the greatest illustration of godly compassion in his willingness to endure an evil execution.

So, could it be that we must not so quickly empty the cross of its victim, nor of alternate reasons that Friday should be called “Good”? Might the crucifix, indeed, be fitting even in our Baptist churches?

So, could it be that we must not so quickly empty the cross of its victim, nor of alternate reasons that Friday should be called “Good”? Might the crucifix, indeed, be fitting even in our Baptist churches?

The crucifix is not only important in the Latin Rite of the Roman Catholic Church, but it has a prominent place in the Eastern Orthodox, Oriental Orthodox, Lutheran, Moravian and Anglican churches as well. Perhaps these Christian siblings of ours have much to teach us.

Often, Baptist congregations will sing a particular hymn on Easter Sunday: “Lo, in the grave he lay, Jesus, my Savior. Waiting the coming day, Jesus my Lord. Up from the grave he arose, with a mighty triumph o’er his foes. He arose the victor o’er the dark domain, and he lives forever with his saints to reign. He arose! He arose! HALLELUJAH, CHRIST AROSE!”

Excitement fills the air, as it should. There are smiles on faces. The praise team on the platform can’t keep from swaying in rhythm. The piano and organ are played as majestically as possible. Jesus is not on the Cross, he is alive!

It’s a cheerful time — a day for wearing our newest clothing, for taking family pictures in front of the flower-decorated chicken-wire cross, for sharing a wonderful meal around a table laden with food and served with the best china and cutlery.

To be clear, I love Easter Sunday also. I have sung that song with enthusiasm and joy. I have worn my best suit and taken those family photos too. I have enjoyed the pot roast and potatoes, the banana pudding and coffee.

“When I see the chocolate crosses, I think that celebratory elements of Easter may have received too much emphasis.”

But maybe we Baptists need more focus on Good Friday. When I see the chocolate crosses, I think that celebratory elements of Easter may have received too much emphasis. It’s not just that candy companies are selling crosses, possibly designed by imaginative Christians, but that these trivial snacks are intended for Christian shoppers, who are expected to buy them.

For many years, as a professor at Logsdon Seminary, I used several video episodes of a 1977 BBC documentary series, The Long Search. In that interesting presentation of religions around the world, London theater director Ronald Eyre explores the meaning of Theravada and Zen Buddhism, Hinduism, Judaism, Islam, Daoism, New Age spiritualities and African religions, as well as Protestant, Catholic and Orthodox Christianity.

The Orthodox episode was filmed in a Romanian village. I was moved by the Good Friday worship. Everyone in the hamlet, it seemed, gathered along the road for the procession of the priest, who ushered them into the small church. At the front of the room, a casket was resting upon two small tables of the same height, leaving perhaps four feet of empty space under the middle of the decorated wooden coffin. At the conclusion of the solemn service, the townspeople lined up and processed toward the physical symbol of Christ’s death, bowing their heads and stooping low to pass under the casket. It made me think of the words that generally accompany baptism: “buried with Christ and raised with him to walk in the newness of life.”

Why does my church celebrate Maundy Thursday and Easter Sunday but not Good Friday? How can so many Christians wear ornamental crosses around their necks or as bracelet charms or dangly earrings, when the original shape instilled fear and loathing?

What exactly is the wonder of the day? And will we sugarcoat his sacrifice by replacing the crucifix with chocolate candy?

Robert Sellers

Rob Sellers is professor of theology and missions emeritus at Hardin-Simmons University’s Logsdon Seminary in Abilene, Texas. He is a past chair of the board of the Parliament of the World’s Religions in Chicago. He and his wife, Janie, served a quarter century as missionary teachers in Indonesia. They live in Waco, Texas.