The so-called “nones” may now have something in common with most American churches: They’ve plateaued, according to Gallup.

Amid all the attention that’s been given to the dramatic growth of this segment of the American population — those who tell pollsters their religious preference is “none” — one recent phenomenon has been overlooked, according to Frank Newport of Gallup: “The percentage of the population who are religious ‘nones’ has remained roughly the same now for six years.”

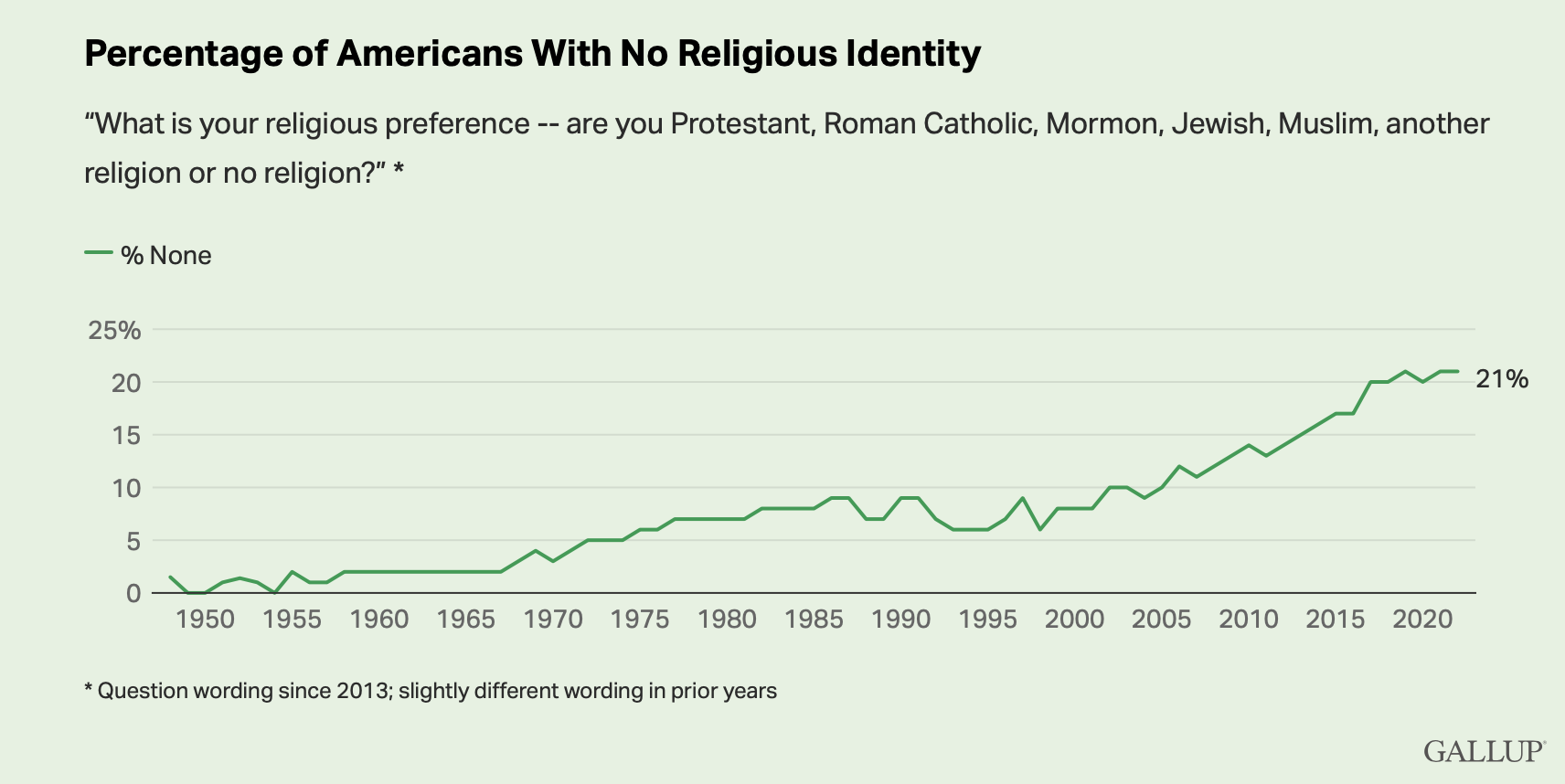

Looking at longer timespans, the nones have grown dramatically. But looking at just the last few years, the percentage of the population identifying as nones has been more stable, Newport said. “The percentage of nones measured in Gallup surveys has risen from close to zero in the 1950s to about one-fifth of the U.S. adult population today. But over the past six years (2017-2022), the rise of the nones has stabilized. An average of 20% or 21% of Americans in Gallup surveys in each of these years say they don’t have a formal religious identity. We are not seeing the yearly increases that occurred in previous decades.”

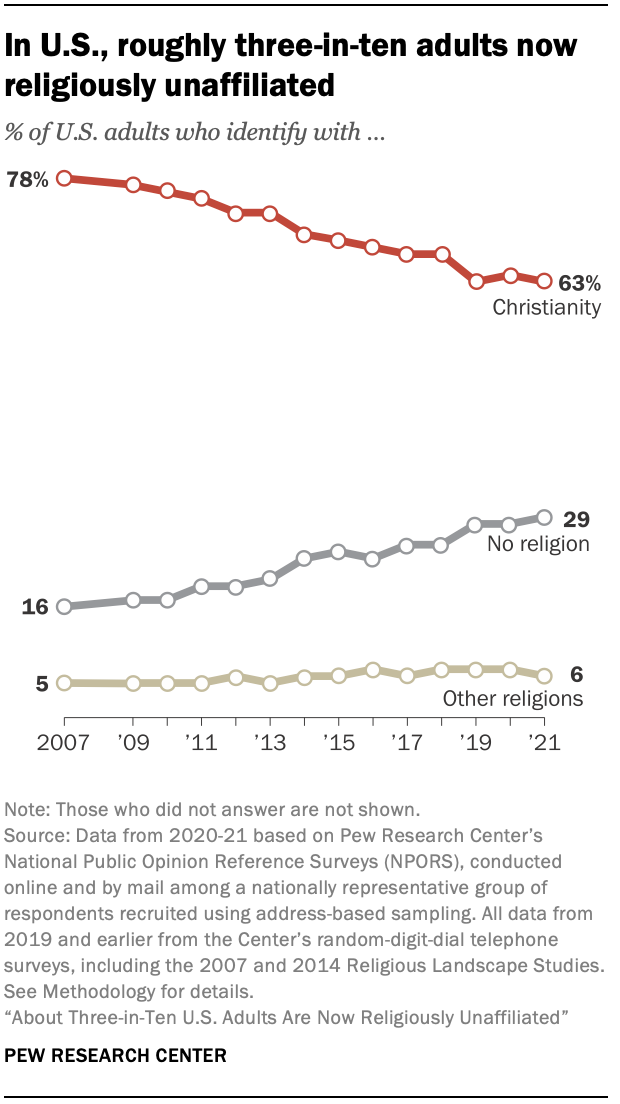

Other pollsters count more nones than Gallup. For example, while Gallup found 21% of the population could be called nones in 2021, Pew Research reported it was 29%. Public Religion Research Institute put the number at 23% that year, reporting a drop from a high of 25.5% in 2018.

Other pollsters count more nones than Gallup. For example, while Gallup found 21% of the population could be called nones in 2021, Pew Research reported it was 29%. Public Religion Research Institute put the number at 23% that year, reporting a drop from a high of 25.5% in 2018.

So are the nones one-fifth of the population or nearly one-third of the population?

“All survey researchers I’m familiar with agree that the percentage of nones has increased over the decades,” Newport said. “But there are differences — sometimes significant ones — in the precise estimate of how many nones there are and in the precise nature of the changes over time. This variance reflects differences in survey methods and question wording across survey organizations.”

Of note: Gallup first started asking about religious affiliation in the late 1940s, but the survey gave only three options: Protestant, Roman Catholic or Jewish. The option to report being Mormon or Muslim came later. It was not until the early 2000s that Gallup added the phrase “if any” to the question: “What, if any, is your religious preference?” And it was not until 2005 that Gallup added “no religion” as a possible response.

The question today reads: “What is your religious preference — are you Protestant, Roman Catholic, Mormon, Jewish, Muslim, another religion or no religion?”

Talking about the nones has become a stand-in for the decline in American church attendance and church membership. If people are leaving churches, where are they going? Some still claim the faith but are inactive, while others claim no faith and become nones.

Now, Newport says Gallup’s data show the share of nones in America is no longer rising based on its specific polling.

“Few Americans were nones in the 1950s, when Gallup began routinely asking the religious identity question,” Newport said. “That percentage rose to just under 10% by the 1980s and basically stabilized over the next couple of decades. Then we saw fairly steady increases in the 2000s until 2017, when — as noted — the trend has stabilized once again.”

But this isn’t the only question that matters, Newport said. “There are other measures of religiosity, and they don’t all show the same patterns. For that matter, they aren’t all measuring the same underlying dimension of religion. Those with no religious identity can still be religious, as measured by their responses to other questions. And those who identify with a religion can be quite irreligious, based on their responses to those same questions.”

One of the best measures, he believes, is the self-reported importance of religion. “It, like the trend for religious nones, has shown a decline in religiosity among Americans over time. But, as is also the case with identity, religious importance has been fairly stable over the past several years.”

Church membership and church attendance have not — compounded by the pandemic.

Newport, who was raised as the child of a Southern Baptist seminary professor, has a hypothesis for how to account for the varying measures: “It is more culturally acceptable now to state publicly that one does not have a religious identity than it was decades ago. The rise of the nones, arguably, measures cultural shifts as well as it does a person’s underlying relationship to religion. An individual may be more willing to tell an interviewer they have no religion than they were several decades ago — because the normative culture has changed, not their internal religion. And the leveling off of the percentage of Americans who are nones suggests that these cultural shifts may have slowed down in recent years — or that the previous suppression of willingness to say one has no religious identity has been reduced to a more stable, lower level.”

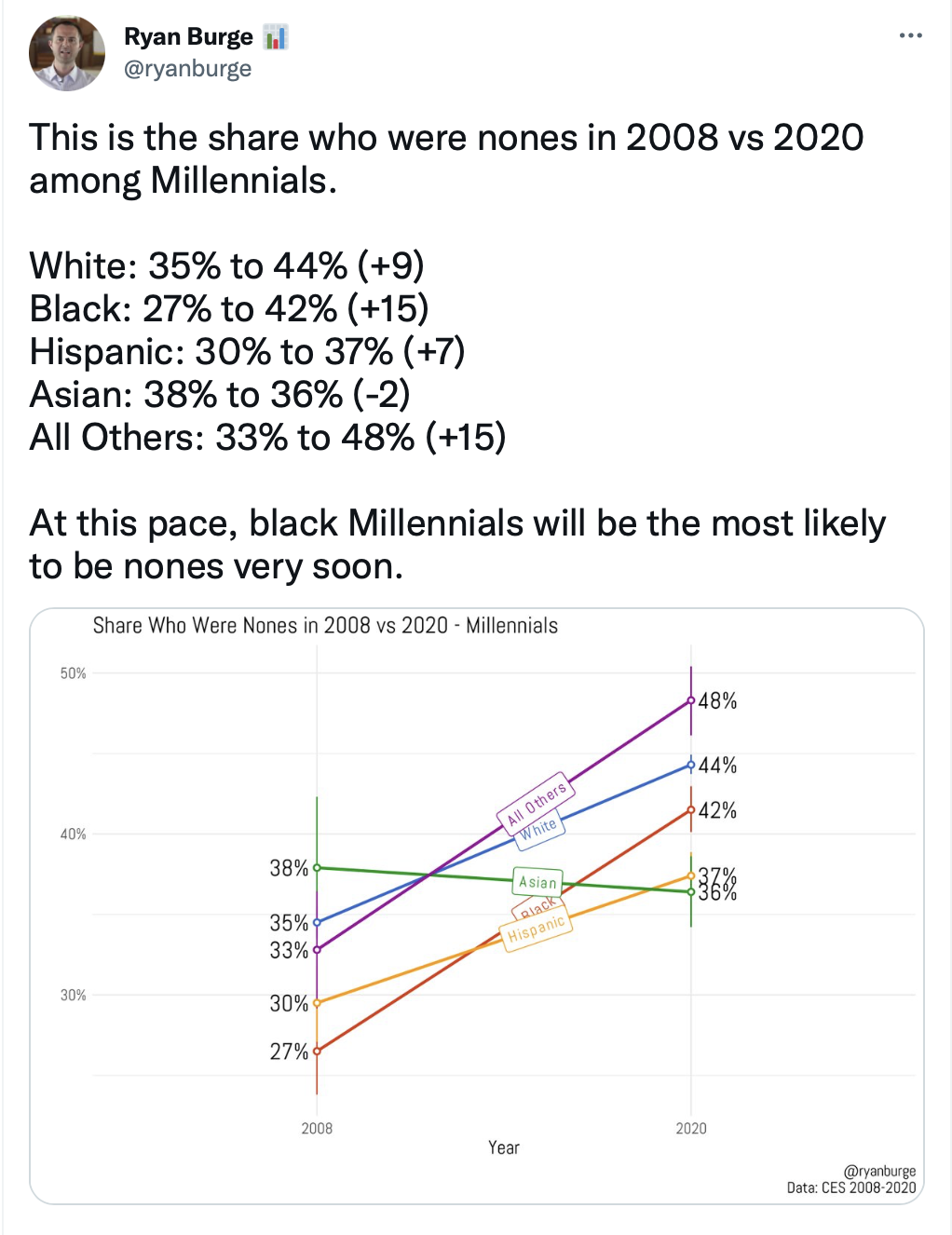

Ryan Burge, an American Baptist pastor and religion researcher, has written a book specifically on the nones and tracks their data weekly through posts on Twitter. He recently posted a graph showing the sharp uptick from 2008 to 2020 among Millennials by race. He points out that Black Millennials could outpace white Millennials in the share of nones.

Ryan Burge, an American Baptist pastor and religion researcher, has written a book specifically on the nones and tracks their data weekly through posts on Twitter. He recently posted a graph showing the sharp uptick from 2008 to 2020 among Millennials by race. He points out that Black Millennials could outpace white Millennials in the share of nones.

The one undeniable reality is that there are many more nones today than even 10, 15 or 30 year ago.

“There were virtually no nones in the 1950s when Gallup began asking the question,” Newport said. “Religious identity at that point was more like an ascribed characteristic — something immutable like race or ethnic identity. In recent decades, religious identity appears to have become a more fluid, achieved characteristic — moving from a rigid identity to an individual choice variable.

It is not inevitable that the share of Americans who identify as religious nones will continue to grow year after year, he said. “History tells us that the only constant when it comes to American religion is change.”

Related articles:

Ryan Burge sifts the data to paint an evolving portrait of the ‘nones’

What to do with the nones? | Opinion by Bill Wilson