Another new year has come, and I have a new year’s resolution — actually a rerun of 2020 that never clicked. Clean out a stack, or two, of “When I get a moment, I want to read this” newspapers, journals and magazine articles.

More than once, I have been embarrassed by noticing stacks of articles and spotting the date of publication. And during end-of-the year file sorting, more than one yellowed newspaper article has snarled, “Hey, what about me?”

Harold Ivan Smith

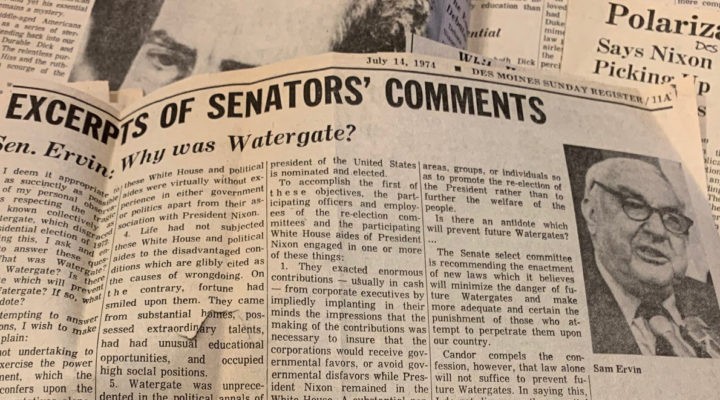

Although I have plenty of my own “to read” articles, during the holidays a friend, after sorting through her stack, mailed me yellowed articles from the Des Moines Register — from 1969 to 1974. Do the math: 51 years ago.

Ah, just what I wanted. Nevertheless, I created another “to be read in 2021” stack for when I get a minute or an hour.

On the first Sunday morning of 2021, I decided, over breakfast, to glance through the yellowed newspapers. I quickly discovered the articles were primarily focused on the Nixon-Agnew-Watergate years. Well, I have books on that era written by prominent historians. No need to save these. But since my friend had made the effort to mail the newspapers, I thought I should at least give a more thorough perusal, dispose of them and get on with the morning’s New York Times.

I made quick work until I hit the section on the Watergate principals, which had a strange affinity to events of the past year, the past week.

The televised Watergate hearings brought to the country’s attention two “gotcha” questions: “What did you know? And when did you know it?” Two questions that have, over the years, been useful in clarifying no few “situations.”

The televised Watergate hearings brought to the country’s attention two “gotcha” questions: “What did you know? And when did you know it?” Two questions that have, over the years, been useful in clarifying no few “situations.”

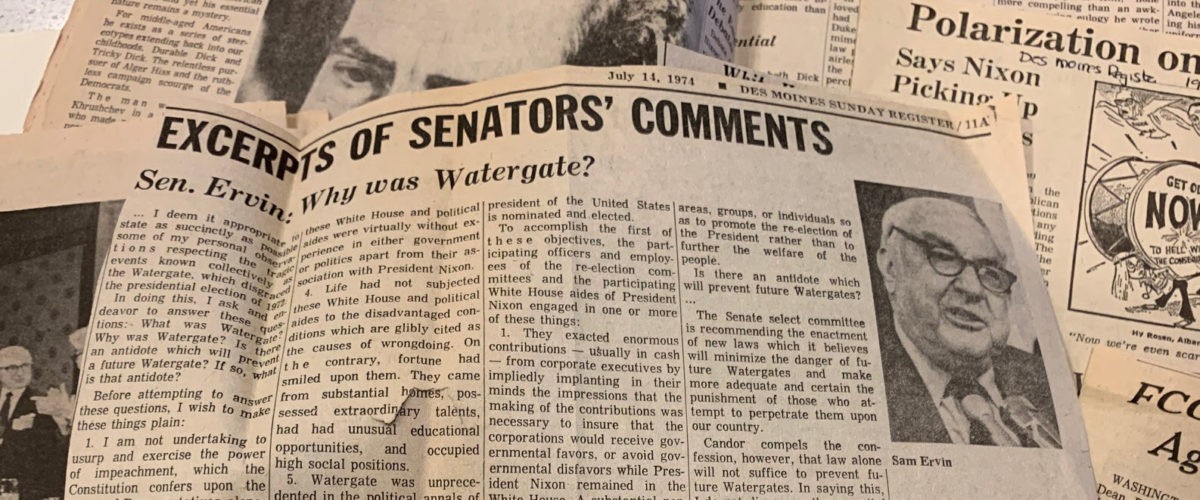

During that summer of 1974, I loved to watch Sen. Sam Ervin commandingly chair hearings of the Senate Select Committee on Presidential Campaign Activities — the Watergate Committee. The aged North Carolinian quoted the Bible and Shakespeare and became something of a fountain of wisdom. He portrayed the perfect image of the Southern gentleman storyteller complete with pauses, voice inflictions and flicks of his head.

Toward the end of the hearings, the Des Moines Register asked the noted “country lawyer” to offer suggestions on how future Watergates could be avoided.

Ervin presented his observations like a seasoned attorney who knew how to “win over” a jury. Because he had been, in his own description, “a country lawyer” who had graduated from Harvard.

As I read the article in my kitchen, I almost could hear Senator Sam’s voice in my head, enunciating his opinions in a beautiful Southern cadence: “No man is fit to participate in politics or to seek or hold public office unless he has two characteristics.” Taking Ervin’s bait, I wondered what the characteristics were.

Senator Sam said: “The first of these is that he must understand and be dedicated to the true purpose of government, which is to promote the good of the people and entertain the abiding conviction that a public office is a public trust, which must never be abused to secure private advantage.”

Why had no one launched a Google search to come up with poignant soundbites from Erwin? I long have admired the clever persistent researcher who has sorted through old videos to find a clip uttered by a politician years ago that directly contradicts a current, politically convenient stance. Oh, so you want to add a justice to the Supreme Court weeks before an election. Given my current political point of view — during a re-election campaign against a tough opponent — “I think it is imperative to get one of ‘our’ judges speedily confirmed.” Then, thanks to the researcher, that politician is confronted with an inconvenient “Oops, I said that?” film clip. “Well, you see, at that time, I may have said that, or believed that, but you have to understand, given the critical need of this hour … surely, you won’t hold me to that opinion.”

To offer another example, “Oh, no, I had said to my broker long before I heard testimony about a potential pandemic … . Why, no, I would never seek to secure personal financial advantage from information I learned in a Congressional hearing. Why it’s despicable that my opponent would try to use this pandemic to his advantage. Besides, I am always trading stocks … .” (What goes unsaid: Surely you don’t think I can live on a United States senator’s salary.)

We have grown immune to the tagline: “I am so-and-so and I approve this message.” Un-huh. So then, will you distance yourself from this latest spun position?

“He must possess that intellectual and moral integrity, which is the priceless ingredient in good character.”

I moved on to Sen. Ervin’s second characteristic (add one more and a poem and you’ve got a sermon outline): “The second characteristic is that he must possess that intellectual and moral integrity, which is the priceless ingredient in good character.”

Some former friends of mine would challenge: “Well, standards have changed since back then. We need someone who can deliver.” Or as one pastor of a tall-steeple church explained after endorsing a particular candidate with moral baggage, “I want the meanest, toughest S.O.B. to protect this nation.”

Surely, if Sen. Ervin were alive today, he would acknowledge what we all know: Politics is about winning and re-winning whether the office sought is dogcatcher, councilman, state senator, governor or president. Besides, “that ‘situation’ was then, this is now. We are all sinners but for the grace of God. Can I get an amen?”

Today, “moral integrity” is, I fear, viewed on a sliding scale of 1 to 10 for too many pew-sitters and Bible-totters-and-quoters. Mortal integrity is “in the eye of the beholder.”

“Well, he’s not nearly as bad as his opponent … . Why, I read on the internet … Everyone knows that she … .”

“Is it reasonable in 2021 to expect higher moral integrity for the candidate than for the voter?”

Is it reasonable in 2021 to expect higher moral integrity for the candidate than for the voter? And does a voter — for the sake of the country — have a right to ignore the eighth commandment: “Thou shall not bear false witness” because, factually, the candidate is really not “my neighbor.”

“For God’s sake, man, we’ve got to hold back the forces of darkness that are perched off our shorelines.” And especially when we believe that this election is the most important in the nation’s history.

Senator Sam offered two creditable characteristics, then concluded with a poem. A candidate reciting a good poem is a lost art in our political climate. Candidates are more likely to dispense zingers or well-rehearsed soundbites.

Sen. Ervin closed: “When all is said, the only sure antidote for future Watergates is understanding the fundamental principles and intellectual and moral integrity in the men and women who achieve or are entrusted with governmental or political power.”

Still, might Senator Sam, as a wise politician, have conceded that in the heat of political campaigns, there are “well, just this once” moments or “the stakes are so high” instances? I do not think so.

Actually, it is the poem the senator cited that moved me. Ervin was from that generation of politicians who as children had been forced — or at least urged — to memorize poems or slices of poems. Some politicians recited particular lines so frequently, smoothly and meaningfully that it sounded like it had become part of their deepest thinking.

Senator Sam set up the poem by crediting the author, Josiah Gilbert Holland, admittedly, “a poet of a bygone generation,” who had described the timeliness of “moral integrity” in an era when you either had it or didn’t. Moral integrity could not just be dragged out of the closet for particular moments.

Harry Truman once said that “moral integrity” is when you do what is right when no one is watching. Although Holland titled his poem, “The Day’s Demand,” Ervin said he preferred to call it, “America’s Prayer.”

God give us men! A time like this demands

Strong minds, great hearts, true faith and ready hands;

Men whom the spoils of office does not kill;

Men whom the spoils of office cannot buy;

Men who possess opinions and a will;

Men who have honor — men who will not lie;

Men who can stand before a demagogue

And damn his treacherous flatteries without winking.

Tall men, sun-crowned, who live above the fog

In public duty, and in private thinking.

As I read the poem a second time, aloud, I thought of the words of Hebrews 11:4, “Abel still speaks, even though he is dead.” (Or as I memorized the verse as a child: “he being dead, yet speaketh.”) Sam Erwin and Joshua Gilbert Holland, though dead, speak poignantly to our day’s political cauldron.

Indeed, the “greats” recognized by the author of Hebrews in public duty and in private thinking acted with moral integrity.

I concede, before readers remind me, that Sen. Ervin did not understand civil rights and gender and race relations with today’s sensitivities. Yet who would have thought that a folksy Southern senator, who quoted Shakespeare and the Bible generously, still recognized by the United States Senate as one of that body’s foremost constitutional authorities, would have something to say to our nation’s fragile and thin bench of potential office holders and those who vote for these individuals?

And who would have thought that a stack of yellowed newspapers could have become holy ground on a Sunday morning?

So, despite your good resolutions to eliminate your stacks, maybe give those stacks of “when I get time” articles a reprieve. I am so glad my friend did not toss that stack years ago. I made time for them to speak to me.

Harold Ivan Smith is thanatologist and independent scholar whose research focuses on the grief of U.S. presidents and first ladies. For 18 years he served on the teaching faculty of Saint Luke’s Hospital in Kansas City, Mo. He earned graduate degrees from Scarritt College, Vanderbilt University, and a doctor of ministry degree from Asbury Theological Seminary. His writings include A Decembered Grief, On Grieving the Death of a Father; Grieving the Death of a Mother; When You Don’t Know What to Say; When a Child You Know Is Grieving, When Your People Are Grieving: Leading in Times of Loss.