Suzanne and Alan Robertson and their daughters found grace, compassion and hope in one of the last places most people would think to look: Death Row.

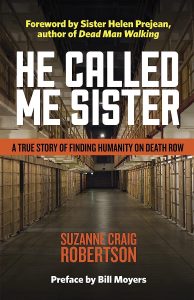

Suzanne Craig Robertson recounts their discovery — and how it touched their lives — in He Called Me Sister: A True Story of Finding Humanity on Death Row. It’s the tale of their 15-year friendship with Cecil Johnson, executed for murder by the state of Tennessee Dec. 2, 2009.

Suzanne Craig Robertson

To be fair, Robertson didn’t go looking for grace, compassion and hope. She found it only reluctantly and understood it more in hindsight than in the moment.

“No, I did not mean to get involved with Cecil,” she confesses. “Yuck. Surely, Jesus didn’t mean for me to dirty my hands with this.”

But her husband stepped up when representatives of Southern Prison Ministry visited Glendale Baptist Church in Nashville, recruiting volunteers to visit Death Row inmates.

Robertson resisted so strongly, she hung up on Johnson the first Thursday night he called to verify his visit with her husband the following day. But she started answering those calls and realized how much she had in common with a convicted murderer — from devotion to their daughters, to joy in cooking, to love of poetry, as well as faith in Christ.

Even then, she couldn’t bring herself to visit Johnson in prison. The night her husband took their 4-year-old daughter, Anne Grace, to see Johnson, she asked herself: “What kind of a mother lets her baby go visit someone on Death Row when she herself won’t even go?”

“A Black Death Row inmate doesn’t call a white suburban woman ‘sister’ without cause.”

As the title of the book indicates, the arc of the Robertson family’s relationship with Johnson curved ever closer across a decade and a half. Even as a Christian, a Black Death Row inmate doesn’t call a white suburban woman “sister” without cause.

Without self-congratulation — Robertson repeatedly notes Johnson gave her family far more than they ever could give him — she describes the bonds that developed between bound inmate and free family: Johnson’s deep affection for Anne Grace and her little sister, Allie. Family game nights in the Death Row visiting room. Shopping quests to find items on Johnson’s wish list, from blue-tinted eyeglasses to frozen cherry cheesecake. The most precious gifts an unfree man could give to beloved friends — free-verse poetry written especially for them.

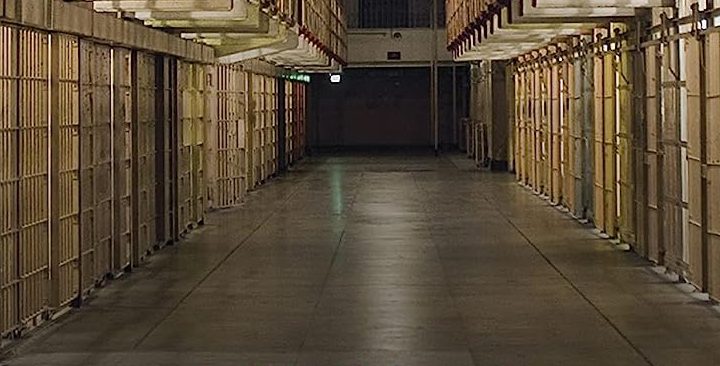

He Called Me Sister tells a tight tale of intimate bonds. It explains how this “chosen” family — an inmate connected to a mom, dad and two daughters who share not a strand of his DNA — celebrated special occasions and deepened their love in prison week after week, year after year. It also describes their mounting grief and dread as legal options dwindled and days leading up to his execution evaporated.

But the book also describes the specific life of a unique man whose story echoes many others’. Johnson typed his memoir on 50-plus single-spaced pages, which he mailed to Robertson. She shares excerpts from that memoir, along with his poetry and letters to her family, to describe that life.

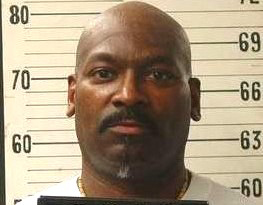

Cecil C. Johnson II

Cecil C. Johnson II was born Aug. 29, 1956, in Columbia, Tenn. He had five sisters and one brother. His father and mother fought, especially when they got drunk. On the day his mother left to escape the abuse, she told her son, “I wish you were dead.”

“On the day his mother left to escape the abuse, she told her son, ‘I wish you were dead.’”

Growing up, he and his younger brother lived with various combinations of family members and sometimes on their own. When his mother finally returned, she came back only to get her daughters. Once, when his father was “punishing” him, the boy pleaded for the man to go ahead and kill him.

As a teen, Johnson learned the value of hard work, whether in low-wage jobs or in higher-wage crime. His big shot at redemption — induction into the U.S. Army — ended after a brawl, long-term confinement and a best-of-bad-options medical discharge. That failure turned him back to a series of legitimate and illegitimate jobs.

Johnson’s background looked ripe for profiling when police sought the person who killed two men and a 12-year-old boy in a Nashville convenience store in July 1980. A Tennessee jury convicted him of murder, assault and armed robbery and sentenced him to death and four consecutive life terms.

But that jury authorized the state to take Johnson’s life despite shaky evidence and misconduct by the prosecutors.

- From the start, he had an alibi and a witness. He was not in Nashville, but about 20 miles south in Franklin, with his friend Victor Davis, looking for women and dice games.

- One witness at the scene initially told police he did not see the murder’s face, and he later chose two other Black men from lineup photos. Then, when he did pick Johnson out of a lineup, he acknowledged he already had seen Johnson’s face on TV in reports connected with the arrest.

- Another witness said the attacker had no facial hair, but Johnson’s mug shot taken several hours later showed he had a fully grown mustache and goatee.

- At the last minute, Davis flipped from being an alibi witness in favor of Johnson to a state’s witness against him — after receiving immunity from prosecution for another crime.

- No physical evidence linked Johnson to the scene, and police never found the money taken in the robbery or the murder weapon.

- In 1992 — more than a decade after Johnson’s trial — the state admitted prosecutors withheld evidence that would have discredited the testimonies of the eyewitnesses to the crime.

Still, a federal appeals court ruled 2-1 the mistakes made in Johnson’s trial did not affect its outcome. Judge R. Guy Cole Jr. cast the lone vote in Johnson’s favor. The jury “saw a markedly different trial than it would have” if the prosecutors had not withheld evidence, Cole wrote. “Because ‘fairness’ cannot be stretched to the point of calling this a fair trial, I dissent.”

With Johnson’s options for other outcomes exhausted, the state executed Robertson’s friend and brother in Christ.

With Johnson’s options for other outcomes exhausted, the state executed Robertson’s friend and brother in Christ.

“You would think that even the slightest bit of room for doubt would keep the government from ending someone’s life, but that is not true,” she observes.

While Johnson maintained his innocence, “I never asked Cecil, ‘Did you do it?’” she notes. “I had plenty of opportunities but never asked. … It would’ve felt harsh and wrong to ask such a thing. You don’t question your friends like that.”

In the end — and long after Johnson’s passing — establishing or believing in his guilt or innocence wasn’t the point of their relationship.

“We started out with the uncomplicated belief that a person’s humanity should be valued, and that person — guilty or innocent, incarcerated or not — deserved compassion,” she says. “Then, as we got to know Cecil as he maintained his innocence, we began to believe him and were eventually convinced.”

According to the Death Penalty Information Center, at least 190 people who had been wrongfully convicted and sentenced to death in the United States have been exonerated since 1973.

Related articles:

One of my pastors is serving life in prison | Opinion by Brad Bull

Opposition to death penalty gaining steam through broad coalition

These Christians are praying for an end to the death penalty

He was wrongly put on Death Row and believes you could be too

Her ‘Damascus Road’ led to campaign against the death penalty

How I came to oppose the death penalty | Opinion by Stephen Reeves