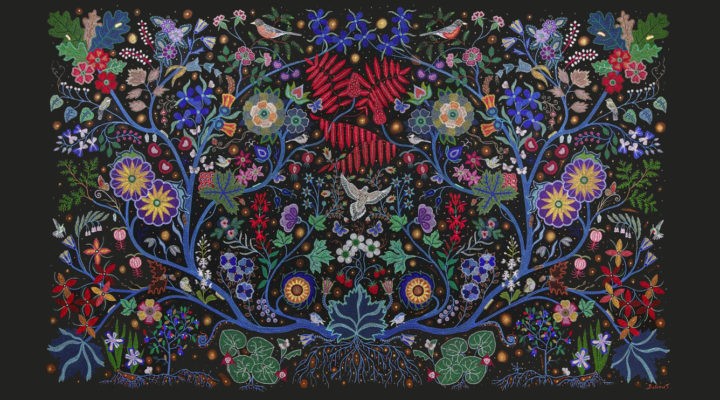

In our world of ecological precarity, I’ve been exploring what it would mean to move beyond doing environmental justice, to living in a different relationship with beings beyond the human.

I think about this relationship both with those beings we consider biotic forms of life, like animals and trees, and those we might normally consider abiotic, inert or “lifeless,” like mountains and bodies of water and weather.

An important part of this work is attending to how language shapes our relationship to everything we talk about in ways both subtle and overt. How we speak, the language we use, the stories well tell, constructs our realities, directs our attention, and helps us know who we are in the world in relation to others. And in my developing relationship with the web of life, terms like “non-human” and even “nature” fail to describe the relationship I am striving to cultivate.

An important part of this work is attending to how language shapes our relationship to everything we talk about in ways both subtle and overt. How we speak, the language we use, the stories well tell, constructs our realities, directs our attention, and helps us know who we are in the world in relation to others. And in my developing relationship with the web of life, terms like “non-human” and even “nature” fail to describe the relationship I am striving to cultivate.

“More-than-human” is a term coined by David Abram that I’ve started to use in place of “non-human” or even “nature.” The term “non-human” rhetorically positions the human in a special and separate category of supremacy over everything else. By using “more-than-human” rather than “non-human,” I’m attempting a way of speaking about a non-hierarchical and non-dichotomous understanding of humanity’s relation to other beings in the universe, decentering the human from a privileged category of existence.

The “more-than-human” invites imaging human life entangled within a larger web of ecological relation that doesn’t privilege the supremacy or exceptionalism of humans, instead situating humans within that larger web on earthly and cosmic scales.

“I like the term because people don’t immediately get it.”

I like the term because people don’t immediately get it. They have to think about what it means. They may be a little afraid of it, even. People are sometimes concerned that it places other beings in positions of supremacy over the human. They’re worried that this sort of elevation of attention to what is other-than-human will mean we’ll run out of attention to give to the humans in the world who are marginalized, victimized and treated with violence and abject disregard.

Importantly, the term — and our discomfort with it — reveals the very roots of injustice and violence against the many humans whose lives must be “reduced” to the status of “nature” in order to be treated as dehumanized beings (like the rest of “nature”).

For one example among so many, the philosopher Georg Hegel (1770-1831) wrote disparagingly about Africans in The Philosophy of History, saying they were “still involved in the conditions of mere nature.” This form of dehumanization, and the racial violence and colonization that results, is made thinkable by drawing upon the ideology of human supremacy over against “nature” and then dehumanizing some to the status of the natural, wild and untamed, so defined by Eurocentric culture or law or Christocentric religion. (Women and LGBTQ people also experience the violence that results from a too-close relationship with “nature,” but that’s another article.)

In response, we want to elevate all people into the same shared category of being human, an appropriate desire, but all the while refusing to dismantle the ideologies of supremacy that allowed for some to be defined out of humanity by relating them to the subjugated and lesser status of “nature” in the first place.

“’More-than-human’ is about refusing to reduce the world and everything in it to a small orbit around the centrality of humanity.”

Injustice and violence, colonization and ecological degradation, may seem like so much more than language, and they are. But they have everything to do with how we name and narrate our relationship with others, human and other-than-human.

So, I am experimenting with language of the “more-than-human.”

The “more-than-human” is about the work of subverting human mastery over everything else in the world that we have decided isn’t “us.”

“More-than-human” is about refusing to reduce the world and everything in it to a small orbit around the centrality of humanity.

From a perspective of biblical creation, it points to the cosmos and the complex web of life on earth taking six days of God’s creativity and the lives of humans only part of one.

It is a term that refuses to let us define every other being from within human-centric categories.

We have for too long spoken of everything “not us” as if it were less than us, there for the taking, for extraction, for destruction, to use as “resources” to benefit us. It’s time to put ourselves in our place — not at the top of a great chain of being, but entangled in a vast web of creativity and creation.

“From a perspective of biblical creation, it points to the cosmos and the complex web of life on earth taking six days of God’s creativity and the lives of humans only part of one.”

Tepid ways of naming the importance of “nature” and the “earth” and even “creation” will not discursively dislodge our felt and imagined supremacy over all that we have imagined and named and narrated as “not us.”

So let’s experiment with the notion of “more than,” because we are entirely interdependent with and, in many ways, entirely dependent upon the “everything else” to live, from the health of our vast lands and oceans and skies all the way down to our human microbiome and the hundreds of trillions of microbes that outnumber human cells in our body 10 to one. We would not be human without the more–than-human.

It is time to develop richer language that identifies our commitment to take seriously and with great care just who we think we are if not the “masters” over all that we so carefully define out of the category of being and belonging to a “human” us over against a “non-human” them.

If you want to try the term for yourself and see what it does for you, don’t try it at your desk or in your living room or even in your church sanctuary. Try it as you sit under the night sky filled with stars. Try it while you are ensconced in a forest of tall, old trees. Try it as you sit on the shore of the ocean with birds overhead and the waves lapping at the shore. Try it as you face the ancient solidity of mountains on the horizon.

Then look at all that surrounds you and say, “What incredible nonhuman things!” See how that feels first.

Then take another long look and say, “There is more. More than me. More than human.” And see how your relationship begins to shift with your language.

Cody Sanders serves as pastor of Old Cambridge Baptist Church in Harvard Square, the American Baptist Chaplain to Harvard University, and the advisor for LGBTQ+ Affairs in the Office of Religious, Spiritual and Ethical Life at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. He is the author and editor of several books on religion and ministry.