I’m not a person who lives with classic depression, but there have been several times in the last few years where I truly didn’t care whether I lived or died. The most recent episode lasted nearly two years.

I chalked it up to the pandemic and the concurrent state of the nation — both of which seemed so out of control that I felt helpless to make a difference. And I suspect I’m far from alone in despairing so much about the present that I gave up dreaming of the future.

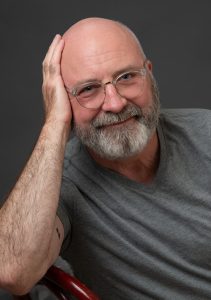

Mark Wingfield

Add to that a major career change in the midst of a pandemic, learning to work from home, and suddenly not being around 30 or 40 people every workday, not making hospital visits, not being engaged in committee meetings (yes, they may be dreadful at the time, but they’re more engaging than you may understand). Imagine an extrovert suddenly sitting at home all day working on a laptop computer.

With the help of a good therapist, there are several things I’ve realized:

- It’s possible to be significantly depressed and still present yourself as a happy person to most everyone around you.

- It’s possible to be significantly depressed and not recognize that you are depressed.

- It’s possible to be significantly depressed and remain highly productive.

- Church staff work can be a joyous hell.

- All of us have a shadow self battling within us for control.

This week, I talked with a Southern Baptist pastor who had just come from seeing his therapist, and he was surprised to learn he could be considered a trauma victim. He had not stopped to think about the battering he’s taken in a fairly high-profile denominational life where critics have come after him on social media and personal messaging for several years.

I reminded him that just the plain-old life of a pastor can be traumatizing on its own. The expectations, the criticism, the constant public presence, and absorbing the pain of those who come to you in need — all these things add up over time. Then toss in some special cause or event, some denominational fight, some family conflict, some financial strain, and you have a recipe for a traumatized pastor.

I didn’t really understand this until about two years ago. I thought I was above all such challenges. I thought I was emotionally healthy. I thought I had tough skin. And I was indeed all those things — until suddenly I wasn’t.

“It’s not enough to refer others to therapy and not practice what you preach.”

Dear pastor friends: If you’re not seeing a therapist, get yourself there right away. It’s not enough to refer others to therapy and not practice what you preach. The work of the church is blessed and beautiful and rewarding, but it’s also draining and demanding and soul-sucking. We all need help.

And dear church personnel committee members: Help your pastors get engaged in ongoing therapy. Reading the Bible three times every day and praying morning, noon and night will not be enough to sustain them in their vital work. The pastor has no one else who is safe to talk to, to spill the beans, to cry with.

On the second visit to my therapist, he said to me: “Thank you for coming back. Most people who are as vulnerable as you were last session are too embarrassed to come back and see me.” That was three years ago, and I’m still showing up.

Many of you reading this column read most everything I write. Some of you tell me you’ve followed my journalism career for decades. You sometimes remind me of things I wrote 30 years ago that I had long forgotten. I am humbled by your kindness.

But deep down inside, I carry the same fear most all of us bear: If they knew who I am on my worst days, if they could see inside my busy mind and read my unfiltered thoughts, they’d never listen to me again.

One of the things I’m learning in therapy is that who we are today does not have to define who we will be tomorrow. I’ve counseled others with that sage advice many times, but I have trouble believing it for myself.

Right here is where in a normal column I would turn to a clever spiritual application of universal value. But I can’t do that this time. This is a story still being written, and I don’t know the ending. I don’t even know the next chapter. Nor do I know how many chapters there will be.

“This is a story still being written, and I don’t know the ending.”

I’ve previously written about the tattoo on my right inner bicep. It’s a semicolon, inspired by a national suicide prevention movement called Project Semicolon. It’s a reminder that when you think your story has hit the end, you should imagine a semicolon rather than a period. The movement’s motto is, “Your story isn’t over.”

I need that reminder every day. And maybe you do too.

For now, I’ve decided there’s more joy in living than I realized — even if the times are scary as hell. I want to know what’s next. I want to experience the next chapter, because I’m regaining the ability to reimagine the good. I’m learning to open myself to a healthy curiosity about what might be, not just what is or has been.

Four years ago, when I first got the semicolon tattoo, I wrote for BNG: “What injury and illness and depression steal from you most of all is perspective — the ability to understand that there’s more to be written in your story.”

That’s as true today as it was several chapters ago. Our stories are still being written.

Mark Wingfield serves as executive director and publisher of Baptist News Global.

Related articles:

A tattoo that says, ‘Your story is not over’ | Opinion by Mark Wingfield

Clergy mental health is a choice between life and death | Opinion by Jakob Topper