As news of Mary Oliver’s death on Jan. 17 began to circulate on social media, my Facebook newsfeed changed. Favorite quotes from the Pulitzer Prize-winning poet kept appearing. Friends posted Oliver’s celebrated questions and described what her one wild and precious life meant to them. Some friends, who would never have pressed “like” on the same Facebook post liked by certain other friends, now found themselves equally struck by the same poem’s truth. Like bouquets brought to a visitation, we marked her departure with those words we found most lovely. We acknowledged our communal sense of loss and gave thanks for her devoted life.

As news of Mary Oliver’s death on Jan. 17 began to circulate on social media, my Facebook newsfeed changed. Favorite quotes from the Pulitzer Prize-winning poet kept appearing. Friends posted Oliver’s celebrated questions and described what her one wild and precious life meant to them. Some friends, who would never have pressed “like” on the same Facebook post liked by certain other friends, now found themselves equally struck by the same poem’s truth. Like bouquets brought to a visitation, we marked her departure with those words we found most lovely. We acknowledged our communal sense of loss and gave thanks for her devoted life.

My newsfeed became a new gift from the poet. Oliver showed once again what words that rise out of wonder could do. “For poems are not words, after all, but fires for the cold, ropes let down to the lost, something as necessary as bread in the pockets of the hungry,” she told us.

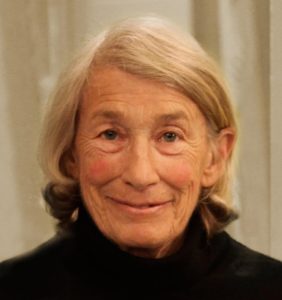

Mary Oliver (Facebook profile)

Oliver became a friend I never met in the middle of a sleepless night when I reached for Upstream, a book of essays. I had admired her poetry, of course, but when I read the essay, “Of Power and Time,” the room spun a bit. It sounded like a personal letter from someone who cared enough to bluntly warn: “The most regretful people on earth are those who felt the call to creative work, who felt their own creative power restive and uprising and gave to it neither power nor time.” Every thrilling project idea I’d ever had, only to be added to a pile of good intentions, suddenly re-introduced itself, making the case that I was a candidate for future regret.

Oliver’s words showed me the gap in which I stood – somewhere between the joy in which I reveled when my faith began and the appealing temptation to make faith more manageable but less vibrant, with less leaping going on. The poet understood: “With growth into adulthood, responsibilities claimed me, so many heavy coats. I didn’t choose them, I don’t fault them, but it took time to reject them.”

Then she pictured more hopeful possibilities: “Now in the spring I kneel, I put my face into the packets of violets, the dampness, the freshness, the sense of ever-ness. Something is wrong, I know it, if I don’t keep my attention on eternity. May I be the tiniest nail in the house of the universe, tiny but useful. May I stay forever in the stream.”

“She didn’t merely leave us warnings; she pointed out trails that could lead us through the woods.”

We read her words and realize what others see in her work: Her “I” includes all of us. She invites us to pray with her for vibrantly eternal lives that begin now.

Oliver befriended us. She didn’t merely leave us warnings; she pointed out trails that could lead us through the woods. In “Sometimes” she offers this path:

Instructions for living a life.

Pay attention.

Be astonished.

Tell about it.

The Church’s work is steeped in words. We’re tempted to skip to the third sentence before experiencing the first two. In my work of editing devotional writing I can tell when a writer has waited until the words were steeped in astonishment. Without ongoing experiences of Grace, we grow opinion heavy. Clichés are never as interesting or illuminating as letting the genuine speak for itself. When our words are born out of an astonished gasp, they start to sing. They gather a wider audience.

“She invites us to pray with her for vibrantly eternal lives that begin now.”

“I did not think of language as the means to self-description,” Oliver told us. “I thought of it as the door – a thousand opening doors – past myself. I thought of it as the means to notice, to contemplate, to praise, and, thus, to come into power.”

In “Praying” she told us more:

It doesn’t have to be

the blue iris, it could be

weeds in a vacant lot, or a few

small stones; just pay attention, then patch

a few words together and don’t try

to make them elaborate, this isn’t

a contest but the doorway

into thanks, and a silence in which

another voice may speak.

What lines would the Church write if we approached Scripture – and our world – with the holy curiosity and expectancy Oliver did when she went to the woods and to the shore? When we stand on the well-worn paths until we hear something fresh, unexpected sounds do grow louder than the thoughts that first brought us there. Words previously unnoticed will catch our gaze and lead us farther than we have walked before.

Oliver hid pencils in the woods near her home so that when poems came to her during her long walks in the woods, as they often did, she always had a way to write them. I think those trees with hidden pencils are a final writing prompt she has left the Church. The joyful work of sharing an astonishing Grace often takes a pencil.