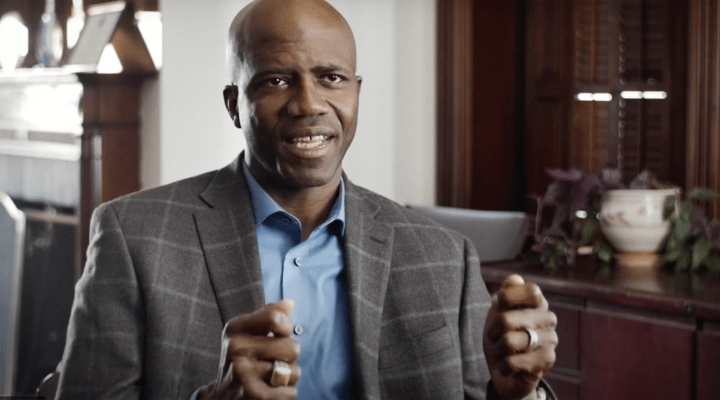

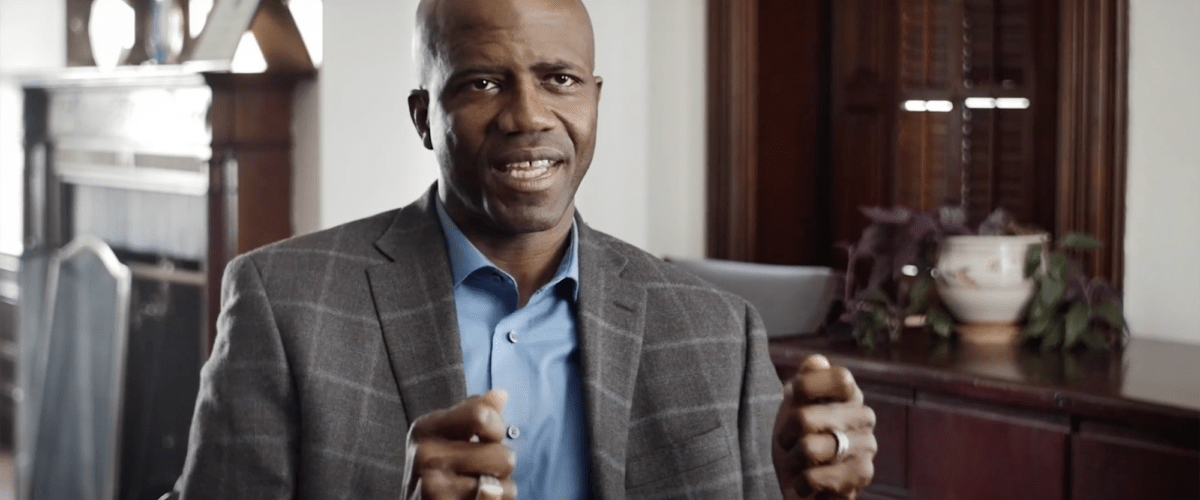

Gary Ivory’s work is to “change the biographies” of at-risk and high-risk youth in 30 states.

“We are not interested in just changing behaviors but the whole trajectory of their lives,” said Ivory, new president of Youth Advocate Programs, a nonprofit that offers mentoring, development and family support services. “We build relationships with young people who are considered at-risk or high-risk, which provides an opportunity to effect deep change instead of arresting our way out of these problems.”

YAP has found that up to 90% of participants successfully complete its six-month program and 85% have not committed new violations up to a year later.

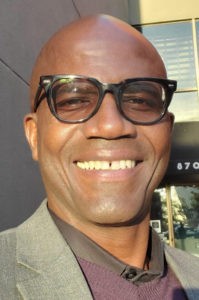

Gary Ivory

Raised in severe poverty in East Texas, he would have been considered “at-risk” himself. Yet he found his way to Austin College in Sherman, Texas, where he earned an undergraduate degree, and then Princeton Theological Seminary, where he earned a master of divinity degree.

Ivory grew up in an East Texas family of 14 children that was so poor its members often had to live off the land. “We had to fish and hunt sometimes when food stamps ran out,” he explained.

Three of his brothers have served prison time, including one who served a multi-year stretch for violently protecting his mother from a white overseer while picking cotton.

“They endured experiences I didn’t have. In many ways I think their traumas were much more severe than mine,” Ivory said.

But he had plenty of pain and grief to deal with himself, and for that he found solace in the church — specifically Spring Hill Missionary Baptist Church in Pittsburg, Texas.

“Early on in my childhood, I lost my father. In fact, I experienced a lot of loss early on, and the church became the place I went to process a lot of this,” he said. A Sunday school teacher took a keen interest in his well-being, and it seemed to him the entire congregation wrapped its arms around him.

He became heavily involved in National Baptist Convention life, and his gifts for speaking and teaching were noticed. “My pastor said, ‘You have a calling to ministry,’ and before that I had a lot of people nudging me along the way,” said Ivory, who was ordained as a Baptist minister at age 16.

“I had all these people loving me unconditionally, and I think that is what made all the difference in my life.”

The all-encompassing care he received from the church and from schoolteachers influenced the trajectory of his vocational calling, he added. “I had all these people loving me unconditionally, and I think that is what made all the difference in my life.”

While in school, he served as a chaplain in hospice care and in a maximum-security prison. He knew already he wasn’t going to become a pastor in the traditional sense of the word. “I wanted to do God’s work in another setting.”

While YAP is not a faith-based organization, his work is definitely faith-based. “I do this work simply because I want to help other people not to experience what I experienced in terms of poverty and to be a part in helping solve some of these systemic family problems,” he said. “I think it’s a blessing that I get a chance to support 20,000 families a year.”

He began working at YAP as a front-line youth advocate three decades ago and has continued to accept new responsibilities ever since. “My calling has always been kind of organic, and it merged into something I care about greatly, which is serving in a way that I can exercise my faith to help people who are struggling.”

Those he and YAP serve are tens of thousands of youth and their families. The organization contracts with law enforcement agencies, judiciaries, correctional and other detention facilities to develop home- and community-based mentoring for young people trapped in addiction, violence, gangs and dysfunctional domestic situations.

Each youth and their family are assigned a paid advocate who coordinates with them to develop individualized service plans aimed at not only avoiding incarceration and recidivism, but to steer their lives in positive directions.

This is the work he calls “changing biographies.”

YAP also works directly with police, housing developments and other community stakeholders through its “violence interruption plan” to preempt gang, retaliatory and other forms of violent crime.

This is possible because local governments and law enforcement have signaled a desire to change their approaches to community policing.

This is possible because local governments and law enforcement have signaled a desire to change their approaches to community policing, Ivory said. “Since the summer of racial injustice last year, a lot of cities and counties are trying approaches that do not rely solely on police response. It’s all about trying to reform the public safety apparatus — how do we respond to at-risk young people, ages 14 to 25, not just with detention or force?”

That takes him back to trying to change biographies.

Such was the outcome for a Philadelphia woman who overcame life on the street by completing YAP’s family focused program.

“Through my YAP experience, I began to see my resilience, which I leaned on during a time after high school when I was temporarily homeless,” Ellana said in comments provided by the organization. “Now I’m totally independent and will be applying to a historically Black college to purse a bachelor’s in criminology.”

Ivory said he wonders what his siblings’ childhoods would have been like if they had benefitted from such program. “As I think back, if we had YAP coming into the home and doing positive activities, I think we would have been much better off.”