When my wife, Priscilla, and I return to Germany for research, we stay at an apartment building in Munich that sits a stone’s throw from the famed English Garden, a magnificent mixture of streams and forest and fields.

Halfway to the English Garden, we pause at the Geschwister-Scholl-Platz. Unremarkable by any measure, this small square sits in front of an immense and austere university building. It has few budding trees, none of the lavish flowers and hedges that can be found a 10-minute stroll away at the majestic Residenz. Beyond its unkempt fountain surrounded by ordinary paving stones, though, the Geschwister-Scholl-Platz harbors the profound story of Hans and Sophie Scholl.

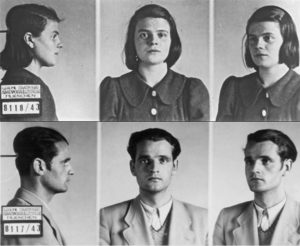

Mug shots of Sophie and Hans Scholl after their arrest by the Gestapo on Feb. 18, 1943. (Photo: National World War II Museum)

Brother and sister, Sophie and Hans were students at Ludwig Maximilians Universität, where Priscilla and I work in Munich. They led a nonviolent movement called the White Rose. In the summer of 1942, they and some friends published six leaflets urging Germans to engage in nonviolent resistance against the Nazis. They covertly distributed these leaflets in their own university. Various doctors, scholars and pub owners received them, as well.

One day, a custodian caught them tossing leaflets in the main atrium of the university. They were arrested by the Gestapo, tried for treason, found guilty and executed on Feb. 22, 1943. “Executed” is a euphemism. They were beheaded in Munich’s Stadelheim Prison. I suppose their lively, curious brains were a threat to the Nazis. It was a telling way to die.

And only for a commitment to peaceful protest. Leaflets, not rifles. Words, not pistols. Ideas, not tear gas.

I am troubled now by images of our own world. Peaceful protesters around our country and around the globe are routinely attacked, teargassed and sometimes apprehended by unidentifiable agents. In U.S. streets, we’ve witnessed shooting deaths that victimized protesters from all points on the political spectrum. In this charged and polarized modern atmosphere, civility has surrendered, too often allowing violent responses to nonviolent resistance.

But such responses are not — must not be — the final word. And that is why, before my early morning walks in the English Garden, I pause at the Geschwister-Scholl-Platz. I remember first the tragedy. Hans and Sophie were arrested, tried and murdered for dropping a few hundred leaflets in a university atrium. In another era, it would have been just another harmless expression of hope.

But such responses are not — must not be — the final word. And that is why, before my early morning walks in the English Garden, I pause at the Geschwister-Scholl-Platz. I remember first the tragedy. Hans and Sophie were arrested, tried and murdered for dropping a few hundred leaflets in a university atrium. In another era, it would have been just another harmless expression of hope.

But I remember, too, the triumph. Their sixth leaflet was smuggled out of Germany and, within a few months, dropped by the millions from Allied planes in special leaflet bombs. The “Manifesto of the Students of Munich,” as it was called, fell like Bavarian snow on a broken landscape. Germany was drenched in the urgency of peaceful protest.

This is what I ponder at the Geschwister-Scholl-Platz, where there is often a petal or two lying on the pavement alongside a few scattered leaflets in bronze. The residue of a white rose — a shy totem to the durable legacy of peaceful protest.

Jack Levison holds the W.J.A. Power Chair of Old Testament Interpretation and Biblical Hebrew at Perkins School of Theology at Southern Methodist University. He is known for his groundbreaking work on the Holy Spirit and topics both biblical and theological.