One of the tasks and joys of my ministry in the last year has been to build relationships with young adults in our community and respond to their needs. Recently, that work brought me out from the walls of the church and into the world of the University of Texas at Arlington’s campus, where I went to visit a peaceful pro-Palestinian protest to listen and to learn.

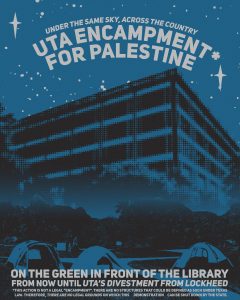

I found out through social media and through my relationships with UTA students that the Progressive Student Union had organized and demanded, like so many others have, that their school divest from companies providing services to the Israeli government or profiting from Israel’s assault on Gaza.

Madison Boboltz

They believe the Israeli occupation of Palestine is oppressive and the unreserved escalation of violence against innocent civilians since Hamas’ terrorist attack Oct. 7 has been catastrophic. They want no part in Israel’s military campaign, which in their view has been much more effective in killing children, destroying hospitals, causing a famine, making the land uninhabitable and causing a refugee crisis than it has been in targeting Hamas and rescuing hostages.

Students want to hold their institutions and government accountable for their part in this, and most importantly, they want to turn the public’s attention to Rafah, where more than a million Palestinians are stuck with not nearly enough resources and aid to survive.

What’s more, Israel is now invading Rafah and has not given those trapped there a realistic or sufficient path out. They are under attack with no way of defending themselves. For these reasons, students urgently raise their voices in favor of an immediate and permanent ceasefire.

The story of Saul’s sons

One of my favorite stories in Scripture comes from 2 Samuel 21. To satisfy the bloodguilt on Saul’s house, King David had Saul’s sons, two of whom were born to a woman named Rizpah, impaled. He left their bodies exposed instead of granting them a proper burial. To protest this injustice, Rizpah set up a one-woman encampment and stayed there for several months.

She “took sackcloth and spread it on a rock for herself, from the beginning of harvest until rain fell on them from the heavens; she did not allow the birds of the air to come on the bodies by day, or the wild animals by night” (2 Samuel 21:10).

Her protest worked. When David found out about what Rizpah had done, he gathered the bones of those who had been impaled and buried them. After that, God heeded supplications for the land.

I was interested to see if this protest would have a similar impact on UTA’s administration as Rizpah’s protest did on King David.

I stopped by UTA on Sunday, Tuesday and Wednesday. When I first approached the students on Sunday, they were gracious and invitational, offering me food, water and a spot in the shade. In my following visits, I watched Muslim students pray together on a specially designated mat laid out on the lawn. I watched students walk around with trash bags, ensuring they were tidy stewards of their campus. I was not present, but I watched highlights from their teach-in with a representative from the DFW chapter of Jewish Voice for Peace, who came to speak on the differences between anti-Zionism and antisemitism.

During one of my conversations with students, we discussed the importance of self-care. I offered some advice on how, as they keep up to date with what is happening, they can avoid the harmful effects of doom-scrolling.

‘A very positive environment’

Sit-in at UTA. (Facebook/Progressive Student Union)

Some students gathered around for these teach-ins. Some studied for finals. Some led “Free Palestine” chants and played on drums. Some passed time by just talking with friends. Through it all, they offered one another moral support, naming all the ways this has taken a toll on their bodies and mental health, but maintaining that their struggles are minimal compared to the dangerous and desperate conditions Palestinians are suffering.

It was overall a very positive environment. The greatest source of anxiety came from the surveillance cameras and police presence, which did not surprise me, but did concern me.

This group was much smaller than those at other universities, and it was beautifully diverse. Among them were Muslims, Black and indigenous people of color and queer students. I immediately worried the police presence was perpetuating a stereotype to folks who might have been interested in joining the protest that associating with students such as these posed a threat to their safety or made them suspect of crimes.

It also felt unnecessary given that these students exercised a willingness to abide by all the university’s standards and protocols — laying out tarps instead of setting up tents and making sure nobody fell asleep — amendments to UTA’s camping policy that have only been in effect since April 24.

Those of you who live in Texas know the last few weeks have been filled with intermittent rain and thunderstorms. These students stayed out there all day and all night, in the storms, completely exposed. Upon receiving the administration’s first response indicating why their demands could not be met in full (you always start off negotiating by asking for the impossible), they revised their demands, clearly indicating they were not out there for the sake of making a scene, but to negotiate for the sake of justice. They gave the administration little reason to challenge their genuine intentions, and they gave the police no reason to arrest them.

Administration intimidation

Even so, administrators accompanied by the police confronted them multiple times to argue that they were out of compliance for storing personal belongings. Members of the community donated food, water, blankets, medicine, etc., which the students stored neatly in totes. They were told that unless they were actively using the donated materials or occupying every lawn chair that was out there, they could not stay.

Students insisted these items had constantly been attended by their group — they had not left anything lying around. In one video from the PSU’s Instagram page, one of the organizers asked what they would have to do to remain in compliance, and the university employee responded that he could not “pre-describe something like that.” In other words, “you can’t” or “you can, but I will not tell you how.”

If you want to give students around the country a lecture that “throwing a fit won’t get you what you want,” then I would challenge you to look at this particular situation on UTA’s campus and ask yourself which party has been most unreasonable.

“The tactics of the police and administrators, as has been the case on many campuses, is to create unfollowable rules that once breached can be used as a way of dismissing and defaming the group.”

The tactics of the police and administrators, as has been the case on many campuses, is to create unfollowable rules that once breached can be used as a way of dismissing and defaming the group. The willfully unclear expectations and enforcement of policies make it impossible for students to be in compliance.

Imagine someone so desperately trying to stop you from getting where you are going that they revoke your driver’s license for speeding in an area where they have the power to actively change the speed limit with little to no notice. Imagine that they make efforts to intentionally block the sign. Imagine they claim you are a threat to the community’s safety when you know that, at the very worst, you were only a few miles per hour over the recently imposed limit.

In addition to problems with the administration, students claimed that in the late hours, they suffered harassment from officers who invaded their personal space and shined flashlights in their faces trying to catch them sleeping.

Obviously, students grew frustrated and angry. They did everything peacefully and cooperatively, and the school still worked to undermine and disband their protest over the collection of essential items such as water and a few empty chairs. I never talked with officers or administrators, although what I gathered during my time out there was that instead of putting energy into meaningful dialogue, they just kept a watchful eye, waiting for the students to be out of compliance with unclear and shifting protocols so they would have a reason to shut them down.

Obviously, students grew frustrated and angry. They did everything peacefully and cooperatively, and the school still worked to undermine and disband their protest over the collection of essential items such as water and a few empty chairs. I never talked with officers or administrators, although what I gathered during my time out there was that instead of putting energy into meaningful dialogue, they just kept a watchful eye, waiting for the students to be out of compliance with unclear and shifting protocols so they would have a reason to shut them down.

I cannot help but remember how, in the Gospels, the scribes and Pharisees became hostile to Jesus and began to interrogate him about many things, lying in wait for him, to catch him in something he might say.

A lesson from Howard Thurman

The police presence and administration’s actions also caused me to remember a moment from Howard Thurman’s autobiography, in which he had to explain to his two daughters why they were not allowed to play on swings at a park: “It is against the law for us to use those swings, even though it is a public school. At present, only white children can play there. But it takes the state legislature, the courts, the sheriffs and policemen, the white churches, the mayors, the banks and business, and the majority of white people in the state of Florida — it takes all these to keep two little Black girls from swinging in those swings. That is how important you are! Never forget, the estimate of your own importance and self-worth can be judged by how many weapons and how much power people are willing to use to control you and keep you in the place they have assigned you.”

“The administration, at the end of the day, cares more about protecting itself and its interests than protecting its students.”

I cannot say I have ever suffered such repression or discrimination, although my own experience of Title IX and LGBTQ advocacy work as a college student exposed me to this difficult truth: The administration, at the end of the day, cares more about protecting itself and its interests than protecting its students. For some, this is common sense; it’s not personal, it’s business. For people like me, who loved that place and thought it would love me back, it was crushing.

I watched these students learn this lesson before my eyes, if they hadn’t already. Like Judas who betrayed his friend with a kiss for 30 pieces of silver, our institutions have betrayed our students, handing them over with little care for their future or the future they are fighting for.

What is so dangerous about two Black girls playing on a swing set? What is so dangerous about students calling for their schools to divest? What is so dangerous about a man from Nazareth criticizing his peers for their neglect of justice and love?

When the high priests went to arrest Jesus, they were accompanied by soldiers with lanterns, torches and weapons. Jesus exclaimed, “Have you come out with swords and clubs as if I were a bandit?” His question bears similarities to those of the protesters around the country: Why do you come at us like you are going to war?

“These absurd and intimidating tactics are how and why protests escalate.”

These absurd and intimidating tactics are how and why protests escalate, first into acts of civil disobedience (a refusal to comply) and then arrests, and sometimes violence. When authorities arrive with a show of force, then like the disciple who raised his sword to strike the ear of the high priest, these students fight back.

Name-calling

On Wednesday, I heard the students call the authorities and administrators names, and I heard them attack their character. They called the police “piggies” and yelled “shame” when administrators were named. As someone who usually finds name-calling and character attacks harmful and unhelpful, it was not easy to hear.

I try to believe that none of the administrators or officers chose these careers because they wanted to silence and threaten college students for their life-saving efforts. I try to believe it weighs on their conscience at least a little bit, and that they are acting on orders or under pressure from their superiors.

I even squirm at Jesus’ occasional public shaming tactics and those instances where he levies personal attacks against the Pharisees, calling them hypocrites and children of hell. Instead of joining these students in the shaming and name calling, I am much more likely to respond to them like Jesus does in the story of his arrest, in which he turns to his well-meaning yet misguided disciple who raised his sword and says, “That’s enough.”

Studenbt protesters at UTA. (Facebook/Progressive Student Union)

My advice to the students in this case, had I offered it in the moment, would have been: “Focus on working the system rather than expressing a blatant desire to have it completely dismantled. For the sake of Palestinians whose lives are on the line right now, save that battle for another day. If you want your demands met, these are the people who, for better or for worse, will play a role in making it happen. They have positioned you as their bitter adversaries; do not give them the satisfaction of proving them right. Calling officers ‘pigs’ is itself a form of dehumanization, which will not help your case.”

There is no way to know if my approach would have been more or less effective. My polite and diplomatic approach to advocacy work in college did not get me very far; the only thing that ever gave me an inch was publishing my thoughts online.

Unless it was coming from a major player, administrators did not exercise true care about student or alumni opposition to their actions until they feared it might mean bad press, and even then they did not budge — they just released more statements insisting they were acting in everyone’s best interests.

Perhaps these students knew that no matter their demeanor, they would face resistance. Regardless of their strategy, I understood the impulse for them to resort to such language. They know what is at stake, and they were exercising holy rage.

Jesus healed the high priest’s ear. Hurt feelings can be mended. As we have seen at other universities, property damage can be repaired. Classes can be held online. Graduating students can find other ways of celebrating their achievements. On the other hand, Israel’s human rights violations and unlawful attacks against civilians, journalists and aid workers are irreversible.

Forcible end to encampment

Thursday, before I was getting ready to head over to UTA, I found out the student protest was forcibly put to an end. The students did not physically resist, and there were no arrests. UTA President Jennifer Crowley wrote, “In consideration of our academic mission, I allowed adequate time for participating students to complete their final exams and to reflect on the potential consequences of their continued activity.” I take this to mean she was waiting for the intimidation to work.

She continued to write that “with the students’ behavior unchanged and final exams concluded, I determined that it was time to end the violations of our encampment policy.” This indicates again she did not take these students or their protest seriously and instead exercised the authority of a parent whose defense to shutting their kid up and putting them in time-out is “because I said so.”

Adults paying tuition deserve more than that.

Perhaps there is more to it. If the administration happens to care about what a community member like me thinks, I would be happy to dialogue and, if convinced, retract these insinuations. As of right now, I am suspicious of their intentions and disappointed by their actions.

Pentecost Sunday

We in the church are coming up on Pentecost Sunday, although as you have probably caught on by now, I cannot help but feel what I have followed and witnessed on UTA’s campus is more like Holy Week.

“They have stayed awake, not for their friends, but for complete strangers on the other side of the world.”

Jesus asked his disciples in the Garden of Gethsemane to “stay awake and pray.” They fell asleep. In their friend’s greatest time of need, they could not even last an hour.

These students have not fallen asleep. Literally and figuratively, they have stayed awake, not for their friends, but for complete strangers on the other side of the world. Trust me, they are exhausted, but no matter how much resistance they encounter, they will keep watch and pray for as long as possible. And I reckon that, as Israel continues its assault on Rafah, they will exemplify the courage of the women who stayed with Jesus until the end. They will not abandon this cause, no matter how hopeless it gets.

While so many of us in the church follow in Peter’s footsteps and deny our Christian calling out of fear — “Hey, aren’t you supposed to be with that Jesus guy who defended the cause of the poor and the oppressed? What are you doing here? Why have you abandoned him?” — these students will be there, weeping at the foot of the Cross, knowing at least they tried.

But they will not be weeping for their innocent adult Savior who willingly bore the cup of suffering and rose from the dead just days later. They will be weeping for the innocent Palestinians — children — who have been given no chance, who have and will continue to die brutal deaths, who won’t be coming back.

Is this the whole story? No. Are there more voices to consider? Yes.

These students, however, have struck a chord with me. I have been reckoning with the church’s response (or lack thereof) to the situation in Israel and Palestine. Even though there is denominational precedent for The United Methodist Church to oppose the Israeli occupation of Palestine, condemn their dehumanizing mistreatment of Palestians and urge the U.S. government to end all military aid to the region, there has been little mobilization among congregations or church leaders to provide aid (acts of mercy) or hold our government accountable (acts of justice).

We have largely left this work to caucuses such as United Methodists for Kairos Response and movements among seminary students. In this crucial moment, our churches can and should do more to amplify these voices, utilize their educational, liturgical and action-oriented resources and support these movements financially. At the very least, we must model ways for our congregations to think about, learn about, pray about, talk about and act on these issues.

“We fear the same things these universities fear: disruption of the ‘peace’ and a loss of privilege and favor.”

But we fear the same things these universities fear: disruption of the “peace” and a loss of privilege and favor. We fear what speaking out will mean for our other ministries that depend on community support. We fear the inaccurate accusations that we sympathize with terrorists and hate Jewish people. We fear the work it will take to convince people otherwise, which will involve digging deep into our own histories of colonialism, nationalism, white supremacy and the weaponization of religious ideologies.

Years ago, we would have been the ones to tell those little girls they could not play on our swings; even if we felt compassion for them, it would have been too dangerous. And I guess the church believes itself too fragile for that.

But as Jesus himself suggested, the kingdom of God is inherently disruptive. True followers of Christ can handle a little discomfort, and division is not always a sign we are doing something wrong but a sign we are doing something right.

In his 1967 speech “A Time to Break Silence” addressed to clergy and laymen concerned about Vietnam, Martin Luther King Jr. said: “When the issues at hand seem as perplexed as they often do in the case of this dreadful conflict, we are always on the verge of being mesmerized by uncertainty; but we must move on. … This is the calling of the sons of God, and our brothers wait eagerly for our response. Shall we say the odds are too great? Shall we tell them the struggle is too hard? Will our message be that the forces of American life militate against their arrival as full men and we send our deepest regrets? Or will there be another message, of longing, of hope, of solidarity with their yearning, of commitment to their cause, whatever the cost? The choice is ours, and though we might prefer it otherwise we must choose in this crucial moment of human history.”

Perhaps my choice to even show up for these students and share these reflections suggests that I am beginning to feel some of that Pentecost spirit after all, for when the Holy Spirit came from heaven like a rush of violent wind and rested like flames upon the followers of Jesus, they began to speak.

Blessed are the peacemakers.

Madison Boboltz is a graduate of Hardin-Simmons University, where she studied religion and psychology, and Boston University School of Theology, where she earned a master of divinity degree in 2023. She serves as a pastor in The United Methodist Church, currently serving at First UMC Arlington, Texas, as associate pastor of adult formation.

Related articles:

We have a teachable moment, and we’re blowing it | Opinion by Susan Shaw

What is going on at America’s elite universities? | Opinion by Mark Wingfield

From the Protestant Reformation to Columbia University, some thoughts on protests | Opinion by Patrick Wilson