Scott, a 63-year-old former chef and factory worker, was trudging toward the tent encampment where he lived on the outskirts of Richmond, Va., when he found fellow camper Ed sprawled on the path, unconscious.

“It scared the hootenannies out of me,” Scott admits. Turns out Ed had collapsed from heat exhaustion; high summer in Richmond usually features blistering heat and swamp humidity — especially this year. It could have been much worse. Ed, 57, has serious heart trouble and back issues, among other health problems.

“I can’t sit or stand very long,” Ed says. “When I lie down it feels better, but when you’re lying on the ground … .”

Other members of the camp group included Ed’s wife, Lisa, also in her late 50s, 63-year-old Denise and 64-year-old Mickey. They found the campsite, in a wooded area behind a grocery store on Richmond’s far eastern edge, after being evicted on 24 hour notice — twice — from more visible tent encampments downtown.

One cop told them the reason for the eviction: “If you’re out of sight, you’re out of mind.”

Richmond, like many urban areas, is quickly sprouting high-rent apartments and condos, restaurants and entertainment venues in the race with other cities to attract affluent young workers and new businesses. It’s become a mecca for hipsters, foodies and indie music.

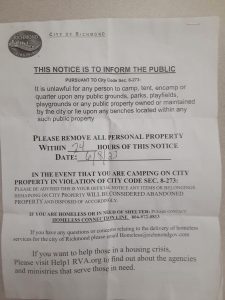

Tent encampments detract from the cool vibe. The unhoused are given a list of emergency numbers to call, along with the city eviction notice posted on their tents. The message: Just be out by tomorrow. Tents and belongings not removed are cleared away and destroyed.

Tent encampments detract from the cool vibe. The unhoused are given a list of emergency numbers to call, along with the city eviction notice posted on their tents. The message: Just be out by tomorrow. Tents and belongings not removed are cleared away and destroyed.

The wooded campsite wasn’t too bad the summer morning I visited, besides the heat and the sodden aftermath of an overnight thunderstorm. Four tents surrounded a community area with several coolers, a small grill and some 5-gallon buckets to sit on for meals and conversation. Extra amenities: a boombox and a few battery-powered lights and mini-fans. Black tarps hanging over clotheslines walled off the “women’s bathroom” (another five-gallon bucket) adjacent to the site. The men found spots to relieve themselves in the woods. My new friends claimed more than 200 other homeless people were camping in the area, including young parents with infants.

Ed and Lisa are from Boston. They lived fairly normal lives there before following their only daughter to Virginia Beach, then to Richmond, where she was attending college. “It went south from there,” Ed says, without going into detail. They soon found themselves homeless.

“The streets are not a place to be when you’re older and you have medical issues,” he adds. “It’s not a place to be when you’re younger, either, but definitely not when you’re in your 50s and 60s.”

He can’t work until he deals with his heart and back troubles. Even if he could work, “you need housing to get a job, but you need a job to get housing. The system is broken.”

Denise and Mickey are more experienced residents of the land of homelessness. That doesn’t mean they like it.

“I’m 63 and I’m out here in a f—— tent,” says Denise, sporting a pink half-top and neon green yoga pants over her stick-thin frame. She’s lost several teeth.

Denise is from Chicago originally. Her husband is in jail. She hasn’t talked to her kids in years. She insists she was paid up on her rent at the apartment where she was living in nearby Petersburg. The landlord kicked her out anyway — maybe to rent to someone willing to pay more.

Mickey hails from a tough Boston neighborhood. He’s weathered, wiry and watchful behind a cheerful Irish bonhomie. He did a long stretch in prison decades ago for murder, but says he learned master carpentry behind bars and also has worked as an electrician and truck driver. He wants to get back to work, but he’s dealing with more health issues than Ed: cancer, hepatitis C, a hernia he can pop in and out at will.

Ed (pictured) and his wife, Lisa, are living in a car owned by their homeless friend, Scott. “The streets are not a place to be when you’re older and you have medical issues,” says Ed, 57. He can’t work until he deals with his heart and back troubles. Even if he could work, “You need housing to get a job, but you need a job to get housing. The system is broken.”

Still, he declares with a grin, “You’re not old if you’re not cold” — meaning dead.

Scott, who flashes a Hollywood smile and a relentlessly positive attitude (considering his circumstances), is from New York. He’s in the best shape of the group, physically and financially. He lost his long-term job back home when his company relocated out of state, then he ran out of money and lost his home. However, he now collects Social Security benefits and a pension (he’s living on the former and saving the latter). He even bought a used car recently.

But he can’t afford even a one-bedroom apartment in Richmond, at least not yet. Rents now average $1,500 and above, if you pass the credit check and have a job. Subsidized housing? Get in line.

I met these folks at the food pantry-clothes closet-shower ministry where I volunteer at Richmond’s First Baptist Church. We’re one stop on a circuit in Richmond where they can find food, a place to clean up and a cool (or warm, depending on the season) room to relax for a few hours. These friends sat at the same table and called themselves “The Collective” — sharing food, supplies and roughly $2,000 in combined monthly benefits to make ends meet.

That was until they had a big argument over something or other at the camp a week after I visited. Denise and Mickey stayed in their tents. Scott invited Ed and Lisa to move into his car, a smallish four-door sedan. They park overnight in residential neighborhoods, sometimes near First Baptist. Scott and Ed sleep up front; Lisa lies down in back. They eat and drink out of a cooler in the trunk.

Scott lost his job and his home, but he now collects Social Security benefits and a pension. He even bought a used car recently, where he lives with his two homeless friends, Ed and Lisa. “They’re great people,” Scott says. “I can get by, but they truly need help. I couldn’t leave them. This is what I got.”

Recently, Scott began driving for Uber and paying for cheap hotel rooms where the three can sleep in actual beds. Ed was scheduled for back surgery in October, thanks to Medicaid coverage.

“They’re great people,” Scott says of Ed and Lisa. “I can get by, but they truly need help. I couldn’t leave them. This is what I got.”

The new (old) face of homelessness

Living on the street is a bitch. Doing it while you’re getting old is even worse.

I began noticing people with gray hair, or white hair, people hobbling with canes and pushing walkers, soon after I started volunteering in the ministry to homeless people at Richmond’s First Baptist last year.

There’s David, now 65, who struggled for months to get a new government I.D. so he could collect Social Security. And Jim, 71, a long-term street survivor who uses his walker as an all-purpose carrier for his few possessions. He sleeps outside with his cat, Fluffy.

“I just love Fluffy,” he told me one afternoon, over and over. Michael, 61 and homeless for three years, sports a Santa Claus beard. He got booted from a city shelter earlier this year when the weather warmed up and later from a tent camp.

You can die from summer heat almost as easily as from winter cold if your health is already compromised, but “inclement weather” shelters in Richmond close every spring until cold weather returns.

They’re part of a growing cohort: Nearly 250,000 people age 55 and over were homeless (or unsheltered, unhoused, experiencing homelessness, if you prefer those terms) in all or part of 2019, the most recent year for which federal data are available. That was 16.5% of the national homeless population of 1.45 million.

David, 65, has struggled for years living on the streets of Richmond, Atlanta and New York. He’s now renting a room in Richmond with his Social Security benefits, but he has medical problems with his leg and Crohn’s disease.

“It’s just a catastrophe,” Margaret Kushel, a professor of medicine and vulnerable populations researcher at the University of California in San Francisco, said in a May interview with the Washington Post. “This is the fastest-growing group of people who are homeless.”

Dennis Culhane, a professor and social science researcher at the University of Pennsylvania, predicted the number of homeless people age 65 and over will double or possibly triple from 2017 totals before peaking around 2030.

“It’s in crisis proportions. It’s in your face,” Culhane told the Post. “Average citizens can see people in wheelchairs, people in walkers, people with incontinence and colostomy bags making their living out of a tent.”

Causes and complexity

What’s going on? A lot.

The 70 million children of the Baby Boom are aging. The youngest Boomers turn 59 this year. About 10,000 Boomers turn 65 every day (I’m now one of those). America as a whole is getting older, on average, and will continue in that direction as long as we approach negative population growth (U.S. population grew a measly 0.38% from mid-2021 to mid-2022) and make it hard for immigrants — the primary source, at the moment, of babies and economic growth — to enter the country.

As Americans age, so will America’s homeless population. But the causes of aging on the street go deeper than demographics.

Steve Blanchard, minister of compassion at Richmond’s First Baptist Church, has assisted homeless people for more than 30 years. Finding more effective ways to do it is his current priority. “It’s hard just to get churches to work together,” he says. “It’d be nice if we could all set aside our own agendas and come up with one agenda that focuses on the needs.”

Drug and alcohol addiction and mental health issues continue to account for many broken lives. Young addicts become old addicts without treatment. The same goes for mental illness.

The Great Recession of 2008-2009, the worst economic downturn since the Depression of the 1930s, laid waste to millions of jobs and lives. It continues to reverberate more than a decade later. The COVID pandemic has caused enormous economic damage over the past three years. Boomers generally have failed to save for retirement or have been unable to do so because of the cost of day-to-day living.

Looming over everything else, housing costs — whether for mortgages or rents — have skyrocketed. Affordable housing no longer exists in many communities. Young professionals on the rise can’t afford to buy houses or rent decent apartments — much less aging working-class and poor people. COVID-era moratoriums on evictions have expired.

The nation’s health care system is not equipped to treat the poor or the homeless. Shelters and free clinics do their best, but a few volunteer doctors and nurses can’t handle the medical issues of aging Americans battered by life outdoors.

Call it “treat and street.” People get “pinballed” from the street to shelters to emergency rooms to short-term facilities — and back to the street. Next stop: early death.

A veteran ER nurse I know in Richmond tells me most of the 50-and-older homeless people she treats show symptoms of poor diet and malnutrition, high blood pressure or heart problems or all three.

The street itself ages you.

“I met a guy not long ago who was 43. He looked 70.”

“A lot of times people have been on the street for a long time, and they’re used to it; that’s their way of life,” says Steve Blanchard, minister of compassion at Richmond’s First Baptist, who has worked with homeless people for more than 30 years. “The thing about homelessness is, sometimes it’s hard to tell who’s older and who’s not. I met a guy not long ago who was 43. He looked 70.”

More often, however, a precipitating event — usually related to finances or social connections — starts a downward spiral for older people. A job is lost. A mortgage is foreclosed. An eviction occurs. A family member dies and their income disappears. A vital connection with family or some other support network is broken.

Kelly King Horne of Homeward

“For older adults, maybe it’s working a low-wage job, or dealing with disabilities. Maybe it’s a medical issue. Maybe it’s behavioral health,” says Kelly King Horne, executive director of Homeward, a nonprofit that works with other agencies, faith groups and government entities to battle homelessness in the greater Richmond area (the city and seven surrounding counties).

“Most homeless programs end up being work programs, where you increase your income to pay rent and get some short-term assistance for that,” she continues. “But for older adults (with declining earning potential), we don’t have a great model. Something happens, and that’s it. They’re facing homelessness.

“I remember a few years ago we had a call from an older couple. Their apartment was condemned because of mold issues. They couldn’t find anything else affordable. Then what?”

Down and out in Richmond

Calls to Homeward’s Homeless Connection Line from people age 60 and older have increased 127% over the past five years. Older adults assisted by homeless aid agencies in the area increased from 29% of total clients in 2018 to nearly 37% in 2021.

Homeward’s “point in time” survey of homelessness in greater Richmond last year counted about 700 people on the streets or in short-term shelters and hotels, 214 of whom were age 55 and older. Both counts almost certainly fell far below the actual numbers. Double them and they still sound like manageable totals compared to the tens of thousands of unsheltered people swarming the streets of New York, Los Angeles and San Francisco.

In theory, yes. But current reality says otherwise — in Richmond and many other small- to mid-size cities with growing homeless populations.

Richmond has spent millions of dollars putting homeless people up in hotels, but it doesn’t have a single city-run, year-round shelter.

Richmond has spent millions of dollars putting homeless people up in hotels, but it doesn’t have a single city-run, year-round shelter. It contracts with private agencies to operate seasonal shelters, which have been plagued with problems. Nonprofits operate other area shelters, which cover only a fraction of the need. Many homeless people loathe short-term shelters, anyway, fearing contagious illnesses, harassment from other clients and theft of their belongings.

Compared to the general need for low-income residents, Richmond has a shortage of more than 23,000 affordable housing units for sale or rent. The city declared a “crisis in affordable housing” this year and declared a goal of creating 1,000 such units annually.

Meanwhile, high-cost apartments and condominiums built by developers from the ground up or from the renovation of former office buildings and warehouses appear almost weekly. They’ve got paying customers.

“When we think about who we welcome as our neighbors, what does that mean?” Horne asks. “Because that’s often what affordable housing conversations come down to. People will say, ‘Well, of course we support affordable housing, just not in my neighborhood.’”

Where, then?

Housing first

There are solutions to the crisis of homelessness. Here are three: Stable, affordable housing. Stable, affordable housing. Stable, affordable housing.

Yes, there are folks out there who choose to live on the streets. I’ve made friends with some of them over the past year or so. But that doesn’t justify the many ways we push the rest out of sight — or look the other way. Most homeless people — particularly older homeless people — would dearly love to have a permanent roof over their heads. Emphasis on permanent.

“It’s tempting to think, ‘Oh, I got them into a shelter, so I’m done,’’’ Horne says. “But you’re not done. Where do they go after that? We always talk about permanent housing because it’s worth starting with that end in mind. It doesn’t happen without intentionality.”

Cities, nonprofits and faith groups around the country are experimenting with ways to make stable housing for the homeless happen. Hotels and empty warehouses can be turned into affordable apartments. Abandoned houses can be renovated and restored. Developers can be required to rent a certain percentage of new apartments to low-income residents.

Eden Villages tiny home

David and Linda Brown, a retired Christian couple in Springfield, Mo., no longer could bear going home to their warm bed after watching homeless people walk into the dark and cold Missouri night from the church-based community center the Browns led. So they pioneered a visionary concept called “Eden Villages,” essentially gated communities for chronically homeless people.

Combining government grants and private funds, they acquire and develop building sites, usually former trailer parks, placing 30 or more tiny homes (400 square feet) beside each other on small, landscaped lots. They build community centers with medical and social services and provide fencing around the site and 24/7 security. Eligible residents are local people who have been homeless for at least a year, with a documented physical or mental disability and the means to pay $300 a month in rent and utilities. Residents can stay for the rest of their lives if they want, or they can leave when they feel ready. They have not only a home, but a community.

The Browns’ original goal was to provide a home for every chronically homeless person in Springfield, and they’re still working on it. But the Eden Village concept is spreading via a franchise model to other cities, including Kansas City, Louisville, Wilmington, Tulsa and Richmond.

Cathy Ritter, a Christian woman in the Richmond area who has served homeless people for many years, is raising money to purchase a former trailer park property and begin construction of an Eden Home site. It will cost millions of dollars in public and private dollars, but she’s determined to enlist hundreds of churches and individuals to help it become a reality.

The Houston model

One of the most successful comprehensive models to end homelessness can be found in Houston, the fifth-largest metro area in the United States with more than 7.3 million people.

Eleven years ago, Houston counted at least 8,500 people on the streets on any given night — one of the largest urban homeless populations in the country. In the years since, more than 28,000 people experiencing homelessness in the metro area have been housed, a 60% decrease in overall homeless numbers. Crucially, 90% of them did not fall back into the street for at least two years.

Marc Eichenbaum

“So, what changed?” asked Marc Eichenbaum, special assistant to Houston Mayor Sylvester Turner for homeless initiatives, and Michael Nichols, president of the Coalition for the Homeless of Houston/Harris County, in a June op-ed for CNN. Here’s the gist of their strategy:

“First, we decided to work together as a collaborative system, aligned around a standardized set of goals, processes and strategies, rather than as individual organizations and government entities each trying to chip away at the problem. Today, more than 100 entities in the Houston area are working together and combining their efforts and resources to move the needle on reducing homelessness. …

“Second, we embraced the data-proven best practices of Housing First, a strategy focused on getting individuals and families out of homelessness and into permanent housing before helping them address any other problems. We do this via voluntary wraparound support services, e.g., mental health or substance abuse counseling, health care, job training and so on. The services help keep the person housed, and the housing is what makes the services effective.

“Third, we housed the most vulnerable people first. When the average person sees someone experiencing homelessness and struggling with mental illness, they assume that individual is dangerous or needs hospitalization. Our experience is that most of these folks stabilize in housing with the appropriate level of services.

“Moreover, we have found that most people fall into homelessness because of rapid and unexpected financial losses — those that needn’t result in catastrophe, if only we had the right policies in place — and that homelessness often exacerbates mental health deterioration and the need to self-medicate. In other words, mental illness is not the driver of homelessness in most cases.”

Bottom line: Collaboration, housing first, followed by wraparound services to prevent a return to the streets. Is it cheap? No. But it’s cheaper than 100 different groups following 100 different strategies.

Power of community

The Houston model is becoming a beacon for many other American cities. Maybe it could work in Richmond. Maybe it could work in your city.

“We’re doing many of the same things,” says Kelly King Horne of Homeward. She’s also on the leadership council of the National Alliance to End Homelessness.

“It’s a smaller-scale problem (in Richmond), thankfully, but we have smaller resources, too. But there’s an incredible power in communities coming together to say, ‘This could be different. It doesn’t have to be like this.’ I know 200 people working today. Some of them are out in the woods (with homeless people) right now. Some of them are working in shelters. Some of them are talking to landlords. Everyone’s bringing their bit to the table. It’s incredibly inspiring.”

We’ll get farther, faster, if we come together to figure out what works. Steve Blanchard at Richmond’s First Baptist is studying homeless programs around the country and meeting regularly with other faith groups and community service providers in Richmond to become more effective.

“It’s hard,” he admits. “I mean, it’s hard just to get churches to work together. It’d be nice if we could all set aside our own agendas and come up with one agenda that focuses on the needs.”