As Americans debate and fret over how — or whether — they will have health insurance in the days ahead, might they once again look to Baptists for a solution?

The creator of modern health insurance was a Baptist layman in Dallas. And the first health insurance plan was created at a Baptist hospital.

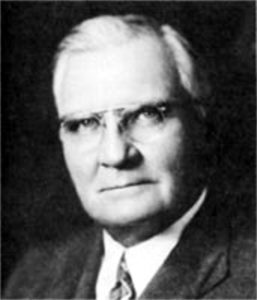

Justin Ford Kimball

In 1929, Baylor Hospital in Dallas had a problem: It was weeks away from insolvency. And teachers in Dallas also had a problem: They couldn’t afford to take time off when they got sick. Fortunately, an unlikely hero in the form of businessman and educator Justin Ford Kimball found a deceptively simple way to alleviate both problems — and gave birth to the health insurance industry in the process.

Kimball, a no-nonsense guy with a penchant for coming up with innovative solutions, left his teaching career in 1929 to take an executive position within the Baylor University system, according to Lone Star Legacy: The Birth of Group Hospitalization and the Story of Blue Cross and Blue Shield in Texas.

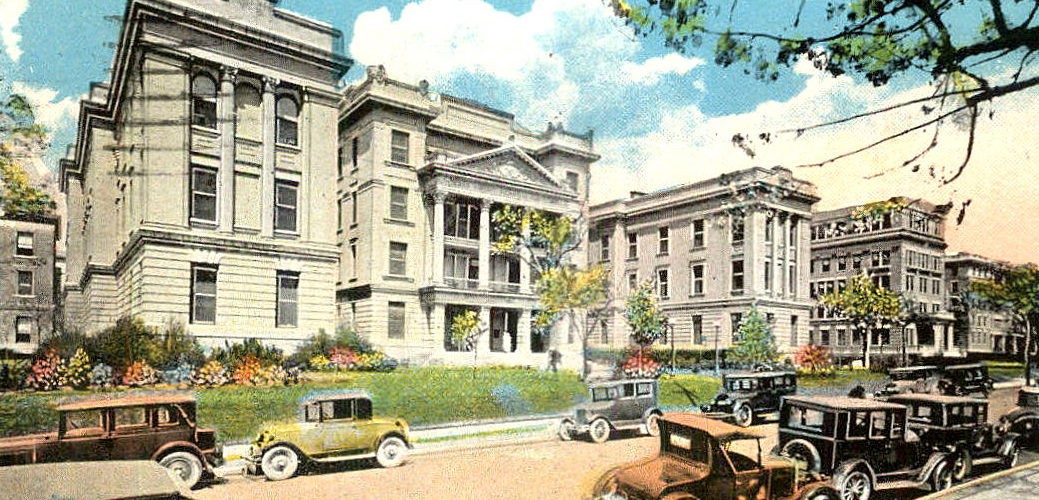

At the time, the Baylor system consisted of institutions in Waco and in Dallas. Kimball was hired to run the “Baylor-in-Dallas” institutions, which included Baylor Hospital and the Baylor colleges of nursing, dentistry, pharmacy and medicine. Chief among Kimball’s responsibilities was to improve the financial situation of Baylor Hospital, which was dire: Its receipts had dropped from $236 to $59 per patient, and occupancy dropped from 70% to 60%.

Baylor, like hospitals across the country, was trying to adapt to serious disruptions to its business model. Up to this point in history, hospitals primarily were financed by churches and other charitable institutions, serving as a last resort for societal outcasts, such as the poor, seriously ill and disabled. As such, doctors rarely visited patients in hospitals, preferring to make house calls instead.

“Up until the 19th century, hospitals were a place you went to die,” said Samuel Schaal, author of Lone Star Legacy. “Most health care was rendered at home by physicians. By the 1920s, it was the early emergence of the hospital industrial complex.”

Evolution of hospitals

A number of factors led to the evolution of hospitals from providers of last resort to providing health care for anyone who needed it, according to Schaal’s book. First, nursing evolved into a true profession, and health care advancements in the mid- to late-1800s, such as anesthesia, antiseptic treatments and X-rays, made surgeries both safer and more common. Additionally, the ranks of the middle class were growing, and more people were moving from rural areas to urban settings, where they relied more heavily on professionals in a variety of fields, including health care.

All these trends created financial challenges for hospitals by the 1920s. Technological advancements made hospitals more expensive to run, and the old financial model where hospitals were supported by churches and other charitable organizations was becoming less viable. Instead, hospitals had to operate less like charities and more like businesses, relying more heavily on payments from patients.

But the rising cost of health care meant many patients were deferring medical care because they simply couldn’t afford to pay.

To tackle the problem, Kimball drew on his decade-long tenure as superintendent of Dallas schools, where, among other things, he created the Sick Benefit Fund in 1921, in the aftermath of the so-called Spanish flu pandemic that began three years earlier.

To tackle the problem, Kimball drew on his decade-long tenure as superintendent of Dallas schools, where, among other things, he created the Sick Benefit Fund in 1921, in the aftermath of the so-called Spanish flu pandemic that began three years earlier.

Similar to the situation today, the 1918 pandemic took an extensive toll on teachers, in part because they weren’t paid well and in part because they weren’t allowed much sick leave. Kimball’s idea was to ask teachers to pay $1 per month into the fund, which would then pay sick teachers $5 for each day of lost pay due to serious illness. The idea was a success, with about 800 teachers signing up to participate. At the end of the year, the fund had a surplus of more than $1,000.

Adapting the model

Fast forward to 1929, and Kimball began to wonder if he could adapt the model he had used to provide teachers with sick pay to address some of the financial strife at Baylor Hospital. The idea of health insurance was not a new one, but it was one that had stumped insurers for decades, according to Lone Star Legacy.

Sam Schaal

It was easy to assess the risk associated with other types of insurance, such as life insurance: A person only died once, and an underwriter could evaluate statistics about a given demographic and predict with reasonable certainty their likelihood of dying within a certain period. It was much more difficult to predict how likely it might be for a certain individual to become sick or injured. For this reason, health insurance companies had started up but gone bankrupt, and other attempts to provide financial protection against illness or injury had not worked well. In short, companies couldn’t predict instances of injury or illness and so could not provide a rate for covering those episodes.

Outside of the insurers, some industries, such as lumber and logging, had tried to provide health care for their employees, with some companies offering on-site doctors. In the late 1910s, a group of textile and paper mills in North Carolina built a hospital for its employees, and a hospital in Iowa developed a plan similar to the one Kimball was contemplating, but it never was adopted widely, as it pre-dated the hospitals’ financing crisis.

The Baylor Plan

Determined to find a solution to alleviate Baylor’s financial woes, Kimball turned to the data he did have — from the participants in the Sick Benefit Fund. In reviewing these records, he found that teachers spent about 15 cents per teacher per month on hospitalizations. With hospital utilization on the rise, Kimball decided to assume that teachers would use triple that amount; then, to be safe, he rounded up, to 50 cents per month.

Justin Ford Kimball poses with a group of educators to promote enlistment for the health care plan.

“The Baylor Plan,” as it came to be known, was extremely simple as compared to the complex medical plans of today. It provided 21 days of hospital care at Baylor Hospital, which included labs, operating room and anesthesia charges. In the event that the hospital was unable to provide services due to overcrowding or any other reason, the plan would pay the member twice the amount of premiums that already had been paid.

The plan was popular from the start, with nearly three-fourths of the district’s teachers enrolling in it — more than 1,300 teachers in all.

“In many respects it was the first health co-op,” said Alan Lefever, director of the Texas Baptist Historical Collection and an adjunct professor at Truett Seminary in Waco, Texas. “Everyone pays in, and from the money they pay in, the plan pays out.”

With a financial model worked out, Kimball now needed people to participate in it. He met with school principals, who were open to the concept of the plan, and then wrote a letter to teachers, explaining that the 50 cents monthly payment was so small that it wouldn’t be missed, and would be well worth it if a person did require hospital care.

Bryce Twitty with Justin Ford Kimball

Brutal winter

The Baylor Plan was adopted against the backdrop of one of the most brutal winters in Dallas history — a fact that quickly put the new plan to the test. The same week the plan was enacted, in December 1929, a Dallas teacher named Alma Dickson slipped and fell on some ice, badly hurting her ankle. Having just signed up for Kimball’s Baylor Plan, she became the first patient hospitalized under the plan. News traveled quickly that the plan paid for Dickson’s hospital stay, helping to popularize it even further.

The work of marketing the Baylor Plan, however, was far from over. That was a job Kimball was all too happy to hand over to a man named Bryce Twitty, whom Kimball had hired as business manager of Baylor Hospital and who had since become superintendent. Twitty met with George Dealey, publisher of the Dallas Morning News, who agreed to let Twitty sell the plan to the newspaper’s employees.

Converting skeptics

Marian Snyder Green (circled in yellow) posing with the staff of the Dallas Morning News. (Dallas Morning News archives photo)

Many were skeptical, much more so than the teachers had been, but one woman, Marian Snyder Green, signed up, not knowing that she would need to be hospitalized just four hours later with a bout of appendicitis. During her hospital stay, Green developed malaria, extending her hospital stay further. Her hospital bill totaled $150 — a hefty sum in those days — but, because she had enrolled in the Baylor Plan, her cost was just the monthly premium of 50 cents.

Hearing Green’s story was enough to convince many Dallas Morning News employees to enroll in the plan, too. From there, Twitty was able to get more companies on board, including General Electric, Republic National Bank and the Daily Times Herald newspaper.

Alan Lefever

“Doctors loved it because they were hurting too; no one was paying their bills,” Lefever said. “This was right at the beginning of the Great Depression, so people were out of money. So there was this group that was going to pay their bills, and they were definitely behind that.”

Significantly, this operating model, where the plan covered hospital charges no matter how high they were, set a precedent that is one factor in the rising cost of health care. Today, the U.S. spends more than $3.6 trillion annually on health care — and the costs keep rising.

The new plan had another drawback: Because the members of the Baylor Plan only went to Baylor Hospital for care, rather than other surrounding hospitals, that limited the number of participants the plan could accept.

“They needed to make sure they didn’t overwhelm the hospital,” Lefever said.

With this limitation in mind, Kimball set a maximum of 34,000 members, and by the end of 1934, the Baylor Plan reached that cap but continued offering services to its existing members for the next decade.

Long-lasting effects

Although the Baylor Plan itself had a relatively short lifespan, the idea soon caught on in various forms across the country, with the Baylor Plan itself evolving into Blue Cross Blue Shield and other plans offering features such as family coverage and benefits at more than one hospital.

Although the Baylor Plan itself had a relatively short lifespan, the idea soon caught on in various forms across the country, with the Baylor Plan itself evolving into Blue Cross Blue Shield and other plans offering features such as family coverage and benefits at more than one hospital.

The concept further expanded during World War II, when employers, faced with wage controls and a tight labor market, offered health insurance coverage to workers in lieu of competitive pay. By 1958, three out of four Americans had health insurance, and by 1960, more than 142 million people were covered.

“Baptists created insurance because there was a need,” Lefever said. “And no matter what, we should never forget that the need for health care and people having access to it hasn’t stopped.”

He added: “Christians have a responsibility to live by the Golden Rule and to look after each other in all aspects of life. In the late 1920s, to do that, Baptists created health insurance.”

This article was made possible by gifts to the Mark Wingfield Fund for Interpretive Journalism.