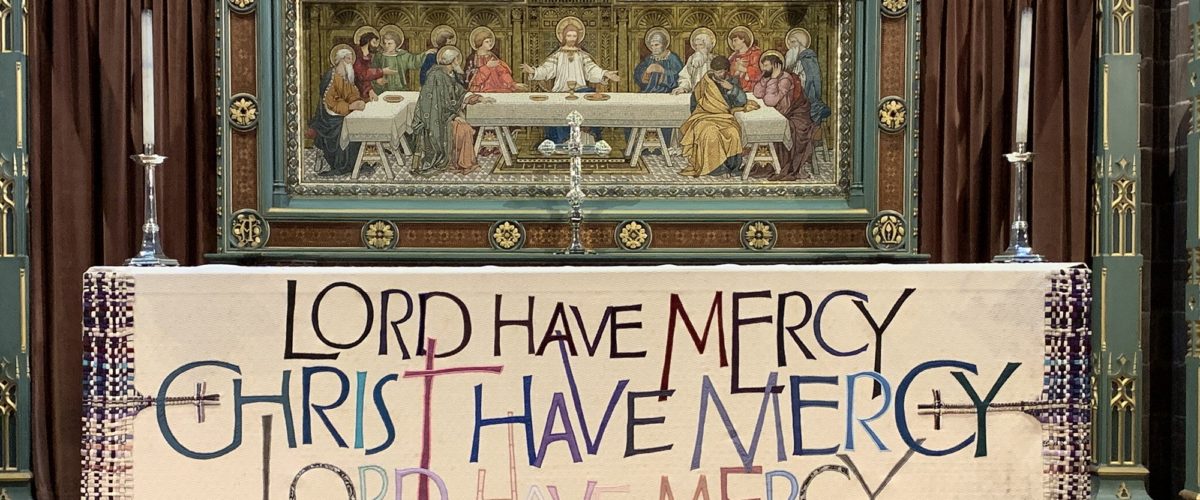

The scene looked the same, just as it does every Sunday: We thanked God for the gifts of the table. Together, we sang “The Sanctus,” and then the celebrant spoke of Scripture — when, at the Passover meal, Jesus takes the bread, blesses it and gives it to the disciples, saying, “Take, eat; this is my body,” then does the same with a cup, saying, “Drink of it, all of you” (Matthew 26:26-28).

When we began to sing “The Lord’s Prayer,” our voices rising to the heights of the cathedral’s arched pillars, it hit me: We sing the same song, even if our approach to the table differs.

Cara Meredith

As I sat in the 112-year-old English Gothic Revival-style building that morning, I reflected on the tradition I was raised in and the one I find a home in now. The granddaughter of a Baptist preacher, a small American Baptist church in Salem, Ore., became my first spiritual home. I was dunked in her baptismal waters and taken in by her Sunday school teachers, youth group leaders and choir directors alike. Her songs, her prayers and her ways of being a part of a church body still live in me, even if I now call the Episcopal Church home.

Of course, the migration from one tradition to another wasn’t something I planned for as a young child or even as a young adult. It just kind of happened. Throughout my twenties and thirties, in a myriad of different towns and cities, a number of denominations became home too. Nondenominational, Presbyterian and Covenant churches became a part of my story, part of a rhythm of finding God along the way.

It wasn’t until a final seminary class on Anglican theology found me Googling “Episcopal churches near me” in a Seattle Public Library one day that I showed up to a midweek lunchtime service and never left.

On each of our journeys, only one truth remains. Whether we crack open an old hymnal, follow along to a series of slides or close our eyes as a soloist sings from the front of the stage, the Baptists and the Episcopalians among us sing a song that honors the same central Christian prayer Jesus taught his disciples to pray.

“We sing to the same God, even if our approach to the Lord’s Supper, baptism and leadership differs wildly.”

We sing to the same God, even if our approach to the Lord’s Supper, baptism and leadership, among other things, differs wildly.

The Lord’s Supper

Growing up, Communion took place on the last Sunday of every month. When the ushers passed around the tray of bread and a second filled with tiny cups of grape juice, we participated as long as we followed in the ways of Jesus. Like most Baptists, we believed in open Communion, and as American Baptists, we believed the specific ordinance symbolized “the broken body and shed blood offered by Christ to recall God’s great love for us — just as they did for the disciples on the eve of Christ’s crucifixion.”

To one writer, however, “The Episcopal church holds the feast in a much higher regard than Baptists and other free church traditions.” Just as Southern Baptists view the Lord’s Supper as a “symbolic act of obedience,” Episcopalians view the Eucharist as one of reverent celebration, the weekly sacrament “the principal act of Christian worship.”

I’ll be honest: participating in Communion every week took some getting used to at first, but now, I can’t get enough of it. It’s the highlight of the service, the pinnacle to which every other element points. No longer is the sermon or the music the most important thing; instead, walking up to the table to receive the bread and drink the wine takes the cake. The crème de la crème of a church service, it truly is a feast.

This is not to say one tradition wins out over the other. Just as we differ in our origins, we differ in our approach to the table. But that doesn’t mean we can’t learn something from one another along the way.

“Participating in Communion every week took some getting used to at first, but now, I can’t get enough of it.”

Leadership

Woven into the fabric of every Baptist denomination is a tradition that highly values church autonomy. When it comes to organization, “Denominational and network leaders provide support and guidance for local churches, but the congregation has the final say on all significant matters.” Similar to a number of other Protestant denominations, whether a community votes quarterly, biannually or annually, Baptists “favor a congregational form of church government in which the members vote on key decisions for their church.”

In order to understand an Episcopal approach to church leadership, one must first start with the word “episcopal,” which comes from the Latin word for “bishop” and the Greek word for “overseer.” Episcopalians, as it goes, adhere to a form of church government that “locates ecclesiastical authority in the office of the bishop.” Unlike the church of my youth, the rules and regulations, the amendments and the resolutions come not from the bottom up but from the top down.

Perhaps it comes as no surprise that I struggled to understand this particular difference when I first started attending an Episcopal Church. If I wanted to start a ministry serving the homeless, why couldn’t I? If I wanted to preach in her pulpit, who’s to say I shouldn’t if I carried the necessary credentials?

So deeply ingrained were values of autonomy within the local body, I felt frustrated by a system so contrary to the way I knew and understood. As luck would have it, I changed my mind or, perhaps, God changed my mind. I began to understand why Episcopalians believe in such holy governance and, at least for me, that alone made all the difference.

Baptism

I’ll never forget the long walk down the red-carpeted aisle of the little Baptist church: Even though I’d knelt by the side of the bed and asked Jesus into my heart a couple years before, I hadn’t yet been dunked in holy waters. Because I was seen as “spiritually mature enough to understand its profound, symbolic significance,” Pastor Jack asked me a series of questions as the two of us stood in the lukewarm waters of the baptismal font. Then, lowering me down into the water, I rose again, resurrected to new life in Christ.

It’s no wonder Baptists are called “Baptists” because of a belief in the holy sacrament of baptism. To many, full immersion not only follows Jesus’ example in the New Testament, but “it also displays the rich symbolism of the gospel by picturing our union with Christ’s death, burial and resurrection.” Additionally, because baptism is seen as a public profession of faith, there is a level of consent that comes from the one who is being baptized.

On the other hand, Episcopalians see baptism as “the foundation for all future church participation and ministry.” It doesn’t matter whether this person is an infant or a grown adult, in every situation, “God adopts us, making us members of the church and inheritors of the kingdom.” Here, baptism happens by pouring and sprinkling (or affusion and aspersion, as the official name goes), instead of by full immersion.

To me, baptism is a powerful experience no matter its expression. Just as Pastor Jack dunked me in 1988, Bishop Gregory sprinkled water over me exactly 30 years later. Although naysayers may dispute the credibility of those on the other side of the theological pond, I can’t help but see the beauty of such an experience. Both were powerful, communal, holy endeavors into the family of God.

Hope aspiration

I return to a song sung in B Flat Major, a key characterized by Schubert as “hope aspiration for a better world.” Wherever we land on a Sunday morning — in Baptist or in Episcopal churches — the tune remains the same.

We sing a song of hope and joy and peace; this our collective desire for a better world. For our God remains the same, even if our approach to central elements differs from one another.

Cara Meredith was raised in the American Baptist Churches in the USA but currently worships as an Episcopalian. She is a freelance author based in the San Francisco Bay Area. Her books include The Color of Life and Church Camp: Bad Skits, Cry Night, and How White Evangelicalism Betrayed a Generation.