Spanning more than 6,000 years, from Neolithic stone circles to the early Christianity of Roman soldiers, from Medieval monasteries to Baptist beginnings, from Darwinism to the influx of immigrants from across the Commonwealth, the history of faith in the United Kingdom is a sprawling and complex subject. And now, for the first time, all that story is told under one roof.

The Faith Museum, which opened Oct. 7, is the nation’s first museum dedicated to preserving and celebrating the country’s diverse expressions of religious faith.

Jonathan Ruffer

Multimillionaire philanthropist Jonathan Ruffer credits his own faith for the founding of the Faith Museum. Ruffer, who became a Christian while at Cambridge University in the 1960s, was in Wales on an eight-day silent retreat organized by the Jesuits when he felt God calling him to do more for those in need.

“It was simply supposed to be a wash-and-brush-up, but when I was there, I was mugged (by God), challenged to turn my life into one that was working with the voiceless,” he later explained.

The former investment banker admits he began his mission sure of a call but unsure of the direction: “It was clear it was what I was called to do. The key was accepting what it was. I always define it as an Abrahamic call, in that I was clearly being sent on a journey, and, like Abraham, I wasn’t vouchsafed the destination.”

Regional renewal

Originally from the northeast of England, Ruffer sought ways to make a difference in an area of the country abandoned by the industries that once supported it. While economically impoverished, Durham County is rich in ecclesiastical history.

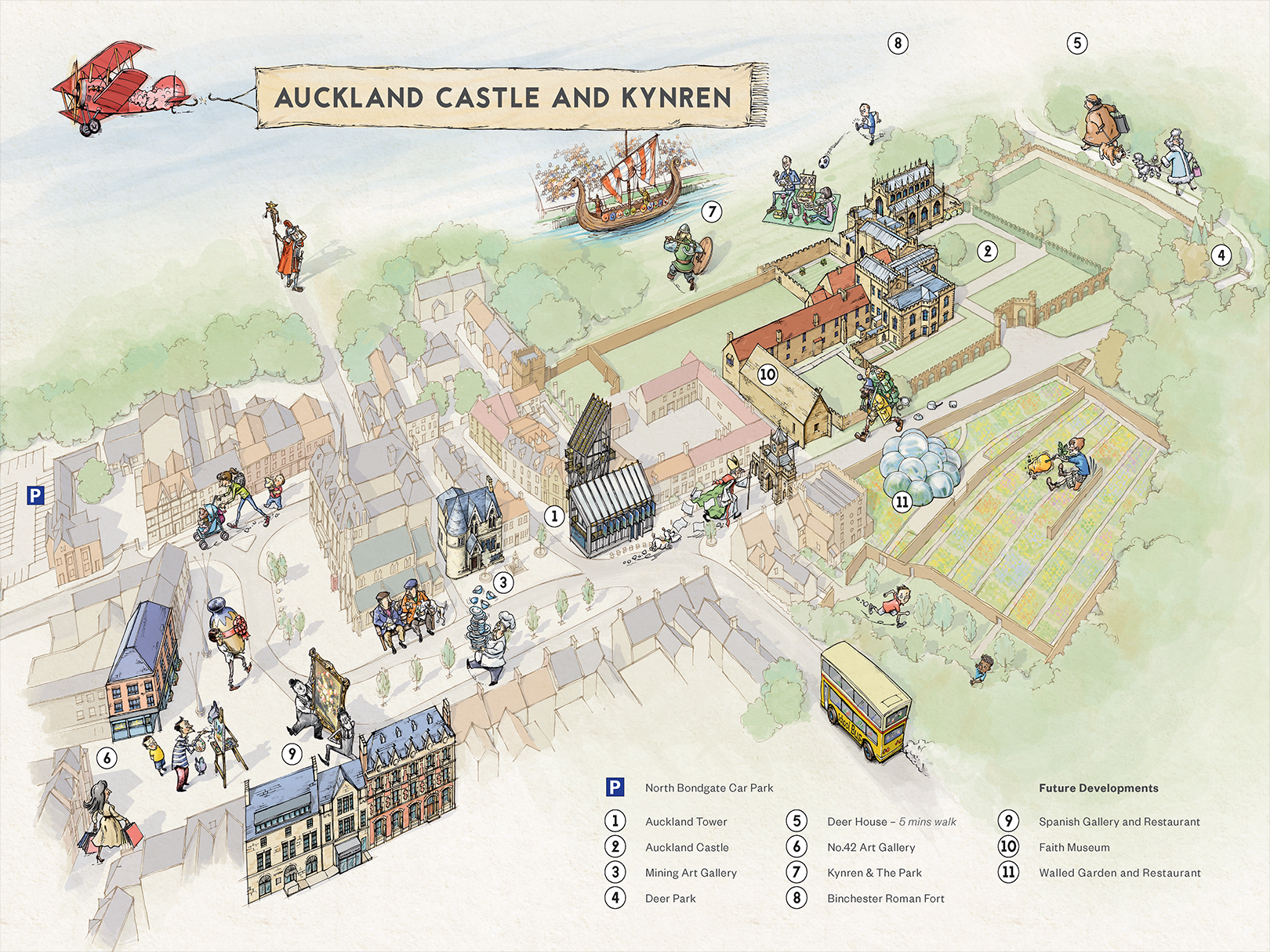

It is home to Durham Cathedral, a Norman architectural masterpiece, and once was the stomping ground of influential Anglo-Saxon theologian The Venerable Bede. At the center of the county is the town of Bishop Auckland and its Auckland Castle. Once the palace of the 11th century bishop prince of Durham, the castle slowly fell into disrepair when nearby coal pits closed in the 1980s and Bishop Auckland’s economy dried up.

Auckland Castle

However, where some saw blight, Ruffer saw opportunity.

In 2013, Ruffer bought Auckland Castle from the Church of England for £11 million in a deal brokered by the archbishop of Canterbury. The castle is now the centerpiece of the Auckland Project, an ambitious plan to boost the area’s economy through tourism. A report by Ernst and Young estimates the project will create 420 jobs in Bishop Auckland and grow the town’s economy by £20 million a year.

The Auckland Project aims to work with the residents of Durham County rather imposing a top-down transformation on the area.

“We do not aim to bring good things to people,” says Ruffer, “nor to do nice things for people. ‘With’ is the key word; we work in partnership with individuals, governments (local and national), other charities, the churches, and all other religions.”

In addition to the tourist attractions, the Auckland Project also provides adults and young people in the community with educational opportunities and apprenticeships.

“What we want with the apprenticeships is for them to move on to good well-paying jobs,” the Faith Museum’s Senior Curator Amina Wright elaborated. “I can see the difference it makes in (these) individuals and in some of our volunteers. It’s lovely to see them blossoming.”

(Photo courtesy of Faith Museum)

New art galleries

To transform Bishop Auckland into a cultural tourist destination, Ruffer has turned Auckland Castle and its surrounding property into a complex of art galleries. Among these is a Mining Art Gallery, inspired by the region’s industrial past, and a Spanish Art Gallery, which complements a series of paintings titled “Jacob and his Twelve Sons” by Francisco de Zurbarán hanging in the castle’s dining room. Bishop Trevor purchased these large portraits of the Hebrew Bible patriarchs in 1757 to show support for Jewish naturalization rights.

“The pictures were going to be sold to a Russian oligarch and that seemed to me to be something of a pity,” Ruffer said. “So, we acquired them, and we acquired the castle, and put them in the trust for the people in the northeast.”

Visitors also may tour the refurbished castle and explore its extensive grounds, some of which are being used to grow food for area food banks.

“We’re feeding bodies as well as minds,” Wright explained. There also is a dog-friendly hotel in the vicinity and various places to shop and eat scattered throughout the attractions. During the summer, guests can watch a live outdoor show about the history of Britain set against the background of Auckland Castle.

“We’re very much involved in the physical regeneration of the town,” Wright said. “It’s things like a new bus station, attracting new businesses to the area, creating new parking and roads.”

The final major piece

The new Faith Museum, built as an extension of the castle’s 14th century Scottish wing, is the final major piece of the multifaceted Auckland Project. With architecture modeled after a Medieval tithe barn, Ruffer created the museum with a £12.4 million grant from the National Lottery Heritage Fund and £100 million of his own money.

Of all the projects he’s undertaken, the Faith Museum is the one closest to his heart, he said. “Everyone operates in the field of faith, just as everybody has a body and everybody has a mind. I think it’s impossible to get through life without addressing questions of faith.”

He has plans to add a faith garden that incorporates the outline of a buried Medieval chapel on the property as well.

The first challenge faced by Senior Curator Amina Wright was how to display something as intangible as faith.

“You can’t put faith in a museum, but you can show what it does.”

“We’re using objects as a witness to faith. Objects from history but also objects from contemporary Britain. You can’t put faith in a museum, but you can show what it does.”

To fill the fledgling museum, she borrowed from public and private collections across the UK. Of the 300 objects on display, 60% are on loan from institutions like the Victoria and Albert Museum and the British Museum. The items give guests a window into the lives and beliefs of those who once owned them.

“Each one of these amazing objects is a sign of something bigger,” Wright said.

“St. Paul Directing the Burning of the Heather Books,” a 16th century tapestry commissioned by King Henry VIII. (Photo by Jack Taylor/Getty Images)

Charting the visitor’s journey

Visitors begin their journey on the basement level of the museum among artifacts of the Neolithic Britons, including the Gainford Stone with its distinct cup and ring rock art. They then make their way upward through the museum galleries and forward in time, passing objects belonging to the Celts, Romans, Vikings, Medieval monks, Protestants and dissenters.

Binchester Ring

One of the stars in the museum’s collection is the third century Binchester Ring, found in 2014 on the site of the nearby Roman fort Vinovium. Its carnelian stone, engraved with an anchor and two fish, is among the earliest evidence of Christianity in Britain.

Elsewhere in the museum is a medal from 1521 commemorating King Henry VIII as “Defender of the Faith,” a title given to him by Pope Leo X. Ruffer and the Faith Museum are currently raising money to purchase another Henry VIII artifact, the tapestry “Saint Paul Directing the Burning of the Heathen Books.” Commissioned by Henry VIII when he declared himself supreme head of the Church of England, the tapestry is currently in the possession of the Spanish government; but Spain is willing to sell it to the Faith Museum for £4.55 million.

Referred to as the “birth certificate of the Church of England” by Ruffer, the tapestry may hang near William Tyndale’s 1536 English translation of the New Testament, which escaped its own book burning. Also at the museum is a wooden pulpit from 1760 once used by John Wesley and a reenforced Salvation Army “bonnet” from the 1900s designed to protect the wearer from bricks thrown at the army band.

The Faith Museum does have a few artifacts associated with Baptist history, but not as many as curators would like. According to Wright, it’s difficult to find early Baptist items with the visual appeal necessary for museum displays because of the value placed on the written word in Baptist theology. While objects from the 17th century Catholic church, for example, are highly ornamental, the Baptists left behind mainly books.

The Faith Museum does have an interactive jigsaw puzzle depicting events from Baptist author and preacher John Bunyan’s book, Pilgrim’s Progress. This digital version is based on a similar jigsaw puzzle from the 18th century and is quite popular with visitors.

In the museum’s Victorian gallery is a “rather strange octagonal plate” featuring a portrait of Charles Spurgeon surrounded by some of the institutions he founded, including the Metropolitan Tabernacle and Stockwell Orphanage.

Elsewhere in the museum is a songbook from Billy Graham’s London crusade and an audio recording of Martin Luther King Jr.’s speech accepting an honorary degree from Newcastle University.

With so many items on loan to the museum, the current exhibits are guaranteed to change as pieces are returned and new ones acquired.

Interfaith focus

While Christianity has been the dominant religion in the history of the United Kingdom, it is certainly not the only vibrant one. The Faith Museum is intentional about displaying objects from a variety of faith traditions in its galleries.

Bodleian Bowl

“We have sought to be multicultural and ecumenical,” Wright said. The Ashmolean Museum in Oxford has loaned the Faith Museum the 13th-century Bodleian Bowl, a rare artifact from England’s Medieval Jewish population. King Edward I expelled the Jews in 1290 and this bowl is “one of the few Jewish objects to have survived,” said Clare Baron, head of exhibitions at the Faith Museum.

“There’s an inscription in Hebrew around the top and it says it was owned by Rabbi Joseph, who we know lived in Colchester,” she explained. “It represents the covert Jewish community.”

The Faith Museum also has on display the prayer beads of Rowland Allanson-Winn, the fifth Baron Headley, who in 1913 converted to Islam and established the British Muslim Society. A model of the Hindu deity Shiva and a Punjab helmet emblazoned with the symbols of three religions also are housed at the museum.

Interpreting contemporary events

Islamophobia and antisemitism are on the rise in the UK in response to the current conflict in Gaza. While intentionally neutral, the Faith Museum is in a unique position to help foster understanding during this time of religious and political strife.

“Religious toleration is a big theme in our story,” Wright said. “We have a very active school program, and I think this is really where we can make a difference. We can get a whole class of kids in for a day and tell them all these stories about what’s happened in the past and what’s happening in the present and get them thinking about, ‘How do you want to live? How do you want to treat other people?’”

As visitors reach the top floor of the museum, they enter the final gallery, which examines the topic of faith in Britain today.

“When it comes to representing the 21st century, we’ve moved away from our approach in the historic galleries, where its more about events that have happened in the past … (and) we’ve handed the galleries over to 10 different artists from all sorts of different backgrounds,” Wright explained.

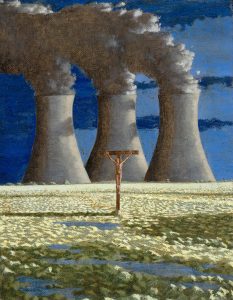

“The Crucifixion,” Roger Wagner

The featured artists are asked to respond to the questions most people ponder when engaging faith: Am I alone? How do I live? Where do I belong? Museum curators hope the artwork will help visitors to reflect on these questions as well. They have refrained from providing detailed explanations beside each piece so that viewers might interpret the art for themselves.

Within this 21st century exhibition, artist Roger Wagner places Jesus and his disciples into modern-day settings, including a crucifixion scene set against the smoking concrete chimneys of the Didcot power station in Oxfordshire. The artists known as the Sigh Twins — sisters Amrit and Rabindra Kaur Singh — combine traditional Indian art with Western art in their painting “Three Golden Rules,” from their Guru Nanak Sikh series. In an immersive walk-through installation, “Eidolon,” Matt Collishaw projects the image of a blue iris engulfed in flames but never consumed. Set to a choral soundtrack, the work symbolizes the moment before the death of Christ or a martyr, which Collishaw hopes brings solace to the viewer.

According to Wright, these pieces are just the beginning for the Faith Museum. “We have a short list of artists we are talking to for the future and plan to include more Muslim artists. People are keen to work with us.”

No proselytizing

While the Faith Museum was born out of Jonathan Ruffer’s own faith experience, he does not intend the museum to be a conversion tool.

“Faith is an essential elemental force,” he said. “We have no sense of proselytizing. This is everyone’s story. We are as broad as humanity.” He hopes the museum will help those he calls the “faith hesitant” to engage faith, and he seeks to challenge visitors who are more settled in their beliefs.

Most importantly, Ruffer is looking to put his faith into action by transforming the lives of those left behind by Brexit and Britain’s changing economy. “This is a journey, and we still don’t know where we’re headed. What we do know is that we want to be able to partner with everybody in town and in every way we can help.”