Taking lessons from history can be challenging. History is not static. It is not one thing, and historians are constantly revising and changing their interpretations and frameworks for thinking about the past. It may not be helpful to compare the severity of our current political partisanship to other periods of United States history, but comparing how our current political partisanship operates in relationship to the past can help us think about how we frame our perceptions of political opponents today.

In 1959, historian Stanley Elkins published his influential and controversial volume Slavery: A Problem in American Institutional Life. The work was innovative for the time but today is rightfully subject to much critique. In the work, he compared the experience of slavery to the experience of Nazi concentration camps and argued that the U.S. system of slavery had the effect of infantilizing slaves. Neither of these arguments hold much salience today.

Also contained within Elkins’ work, however, is an interesting argument about how white society in the U.S. addressed the problem of slavery in ways that ultimately led to the Civil War. Whereas British anti-slavery advocates centered their fight to end slavery firmly within educational and governmental institutional structures, Elkins argued that in the United States the intellectual energy around abolition operated in an anti-institutional mode.

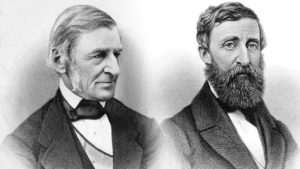

Emerson and Thoreau

Elkins wrote about transcendentalists like Henry Thoreau, Ralph Waldo Emerson and others who removed themselves from institutional life to contemplate society’s challenges often in the solitude of nature. This removal from institutional like, Elkins proposed, was a problem. Issues like slavery were not addressed within the context of the proper institutions that could organize and exert pressure on the larger system. He contended that when operating outside institutions, “reform thinking will tend to be erratic, emotional, compulsive and abstract.”

As these abolitionist and anti-slavery slavery advocates considered the moral travesty of the system of slavery, they internalized this societal sin. Without any institutionalized mechanisms through which to address the system of slavery or assuage their guilt, Elkins contended, the guilt and frustration of these reformers festered and became abstracted.

But at a certain point, this compounding guilt became “transformed into implacable moral aggression: hatred of both the sinner and the sin.” Abolitionists felt guilty for the sins of the Southern Slaveholder.

Elkins put most of the blame for the sectional crisis and Civil War on these anti-slavery advocates and abolitionists who were unable to vent their opposition to slavery in productive and meaningful ways that might have led to change.

I am less concerned about the “blame-game” and the “correctness” of a historical argument (as if there even is a “correct” historical argument) and am more concerned with Elkins’ logic about institutions and abstraction.

The decline of institutions

Over the past few decades, societal faith in institutions has been on the decline. Innumerable studies have shown how Millennials are not the same type of institutional joiners and supporters as were previous generations. The onset of the digital age has changed how we associate with institutions.

Sociologist Robert Putnam’s classic 2000 work, Bowling Alone: The Collapse and Revival of American Communitycontends that community organizations of all kinds have seen sharp declines in membership. Illustrating Putnam’s point, he found that more Americans were bowling at the turn of the century than in 1980, but fewer were bowling in leagues.

“This trend seems to have accelerated since Putnam’s work, as U.S. society increasingly looks upon institutional life skeptically.”

This trend seems to have accelerated since Putnam’s work, as U.S. society increasingly looks upon institutional life skeptically. The 2008 financial crisis has left little trust in financial institutions. There is little trust in the medical community thanks to the work of the pharmaceutical industry. News sources and the press are under intense scrutiny from a distrusting public, to say nothing of our political partisanship and distrust in governmental agencies.

Religious organizations, too, are not immune from this institutional decline. From the clergy sexual abuse and coverups in both the Roman Catholic Church and other Protestant denominations to theological hypocrisy and double standards, wider society has become increasingly skeptical of religious bodies as well.

The abstraction of social media

Coupled with the decline of institutions, social media has warped how we engage social problems. While much of the public has known for years how social media creates an echo chamber that shows you posts and ideas you are more likely to “like” and “share,” the Facebook whistleblower and the release of the Facebook Papers shows just how bad the social networking site has been in dividing society and contributing to our collective and individual anxiety and depression.

Drawing upon Elkins’ logic, the social media platform removes our intellectual and social discourse from an institutional context. Facebook encourages us to consider and process the problems of society individually. We feel guilty for not doing enough, for not doing more.

At the same time, Facebook is not the platform to bring about social and political change. Yes, the tools of social media can and have been used to galvanize large-scale protest movements and other collective responses to societal wrongs, but such responses have only further removed us from meaningful engagement in institutional life.

At the same time, Facebook is not the platform to bring about social and political change. Yes, the tools of social media can and have been used to galvanize large-scale protest movements and other collective responses to societal wrongs, but such responses have only further removed us from meaningful engagement in institutional life.

I can think of no better illustration of Elkins’ understanding of abstraction than an argument on Facebook between two people who do not know each other. Disembodied and, for all the two individuals know, they could be arguing with a sophisticated artificial intelligence program. It’s far easier to be mean-spirited to a screen than to someone face to face. Been there. Done that. Social media allows us to construct caricatures of one another that stand in as symbolic representations for all that’s wrong with the world.

Abstraction of ‘The Left’

In September, conservative commentator John Nolte published an op-ed on the right-wing online publication Breitbartwhere he accused “leftists” of a conspiracy to keep Republicans from getting vaccinated. According to Nolte, “Joe Biden and Nancy Pelosi and Anthony Fauci are deliberately looking to manipulate Trump supporters into not getting vaccinated.” In a weird twist of reverse psychology, liberals were encouraging everyone to get the vaccine because they knew conservatives would do the opposite.

“Nothing else makes sense to me,” Nolte wrote.

Essentially, it was unfathomable for Nolte that Democrats who encouraged individuals to get vaccinated were genuinely interested in saving lives. Promotion of the vaccine by Democrats was not a call to save lives, it was a ploy to kill political opposition. Nolte could not believe Joe Biden would want to save the lives of Americans who voted for another political party. Occam’s Razor be damned.

Nolte abstracts “leftists” into a politically and psychologically calculated faction of U.S. society bent on having coronavirus kill conservatives.

Abstraction of ‘The Right’

There also is a tendency among the left to view the right through abstracted caricatures — as in a basket of deplorables. This is not to suggested that both sides are in the wrong and therefore we must take a moderate, middle-of-the-road perspective either. Proportionality matters.

“As progressive Baptists, this characterization of the right also has the tendency to obscure our own identity.”

Our ability to see beyond simplistic caricatures of the right, however, has been hampered in many ways. Not the least of which, many on the right have come to embrace their caricature, their abstraction. This right-wing populist mentality has embraced a gun-toting, Donald Trump-loving, anti-government persona as a means of “owning the libs.” However racist, sexist and homophobic we may find the far right, reducing their identity to mere caricature only further contributes to our inability to find solutions to our collective problems.

As progressive Baptists, this characterization of the right also has the tendency to obscure our own identity. Identifying the right as racist, sexist, homophobic and more, we suppose that these characteristics don’t also characterize us as well.

While Virginia’s recent gubernatorial race may have been decided in suburban counties, this is because Democrats and Republicans already have decided the outcomes of rural and urban counties. The suburbs — this in-between space — becomes the battleground because it operates in between our obscured and abstracted perceptions of rural and urban, Republican and Democrat, right and left.

Beyond abstraction

None of this is to suggest that history is repeating itself or that we are doomed to an inevitable oncoming civil war. Studying history is not a predictor of future events. Elkins’ interpretation of the antebellum landscape prior to the Civil War merely provides a framework through which to consider the challenges of our current societal climate. There may be and likely are other, more compelling, frameworks.

A painting of Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia fighting the U.S. Army at Spotsylvania in 1864. (Painting/Thure de Thulstrup)

Even so, thinking through Elkins’ understanding of institutional life in grounding practical reform efforts is fruitful. This is what Baptist congregations do at their best. They are local in nature. At their best, they have the capacity to bring into focus what we can only see nationally through generalized abstractions.

As religious folk, I contend that the challenge we face is how to hold these abstractions. Yes, white supremacy, patriarchy and unfettered capitalism among a whole host of other things are morally wrong. These systems are totalizing and soul-crushing. Our inability to “fix” them weighs heavily on us. They presume an equally large response. We must balance our ability to see these large, looming, systematic abstractions, however, with precise and grounded responses.

Andrew Gardner is the Louisville Institute postdoctoral research fellow at the Hartford Institute for Religion Research.

Andrew Gardner is the Louisville Institute postdoctoral research fellow at the Hartford Institute for Religion Research.

Related articles:

America’s divide between left and right more severe than in Western Europe

On the collapse of Christianity into politics | Opinion by David Gushee

In the spirit of Dr. Seuss … | Opinion by Russ Dean