“How did you come to have a passion for social justice issues?” That was one of the questions put to me this week when the tables got turned and I was the interviewee instead of the interviewer.

The answer immediately formed in my mind: Because that’s how I was raised.

But what might be shocking to some is to finish that thought by saying that’s how I was raised as a Southern Baptist in Oklahoma. These days, “social justice” and “Oklahoma Southern Baptist” don’t naturally fall together in the same sentence.

Mark Wingfield

But in my experience growing up in the 1960s and ’70s, this wasn’t so much of a stretch. Certainly, the definition of social justice I knew as a child and teenager wasn’t as expansive as it should have been, and it clearly did not include anything approaching a full measure of racial justice awareness. Yet at its core, what I learned growing up as a devout Southern Baptist in central Oklahoma offered the foundation for a belief system that in time would broaden through personal experience, hard knocks and friendships that formed me even more.

Carefully taught

In their own simple ways, my parents modeled a vision of biblical social justice that I learned by observation. For example, one August before school started, when I was in early elementary school, we took into our home for a few days an orphaned boy from the Baptist children’s home. And my mother — a schoolteacher — took us both shopping for back-to-school clothes. We both got new pairs of stiff blue jeans and new shirts. We were treated equally. In my mother’s eyes, we both were worthy of the same good things. This made such an impression on me that I can still visualize the store 50 years later.

That childhood experience happened because of the teaching and mission of the small-town Southern Baptist church we attended at the time. And likely because both my parents had been raised in poverty and knew what it was like not have new clothes to wear.

Here’s the thing that astounds me every time I think about it: I live a very comfortable life just one generation away from poverty. Both my parents in their lifetimes were able to move from families that scratched out a hard living from the soil to a middle-class lifestyle that their parents and grandparents could not have imagined.

“Here’s the thing that astounds me every time I think about it: I live a very comfortable life just one generation away from poverty.”

They were children of the Great Depression, which shaped my mother especially to be both thrifty and generous at the same time. That’s a juxtaposition I still marvel over.

Southern Baptist socialists?

This thought came racing to my mind last week when reading a fascinating article about the rise of the Religious Left in American life. That article quotes Serene Jones, president of Union Theological Seminary in New York, who also was raised not far from me in Oklahoma and just a few years ahead of me.

She said this: “The big misconception is that the progressive religious voice in this country is suddenly coming to the fore. It has been there a long time. It has a longer history in this country than the evangelical right wing; in the 1920s in Oklahoma, you would be hard-pressed to find a Southern Baptist who was not a socialist. Much of mainline Protestantism all the way back before the Civil War were abolitionists. There’s a long history of deep care for the poor, setting up universities and hospital systems in our country — that all came out of religious communities that had a very progressive vision for what the United States can be.”

Southern Baptists in Oklahoma as socialists? Amazing. And yet that also was my experience — just not “socialist” as in Communists or in the sense of the political boogeyman religious conservatives have created of the word these days.

“There was a time, even in my lifetime, when evangelicals and Southern Baptists cared about the social good as a gospel imperative.”

Her point is true. There was a time, even in my lifetime, when evangelicals and Southern Baptists cared about the social good as a gospel imperative. That’s how it came to pass that I was raised in a Southern Baptist culture that preached an authority of Scripture that believed Jesus was serious when he said to love our neighbors and to care for the widows and orphans. That’s how I was raised to read the Hebrew prophets with alarm as they continued to call us to measure with equal weights and to be found faithful when the plumbline of justice came down from heaven.

Two roads diverged

What happened between then and now? How is it that such an ideological chasm now exists between the church of my youth and the present reality? How is it that — as I like to joke — I wouldn’t be invited back to the church that raised me even to lead in silent prayer?

Who changed? Truth be told, we both did, we all did. My own life experience has drawn me from that biblical foundation to see a wideness in God’s mercy. Others have emerged from the same roots with different views nourished by doctrinal purity, the sexual revolution and our nation’s inability to address racism.

I can’t speak fully for those who have taken a different path in spiritual thought, although I do believe that road has been shaped as much by national politics as by religious devotion. From the Moral Majority forward, we have suffered a cleaving of biblical justice from politics by the selective emphasis of a few shibboleths such as abortion and sexuality.

I can speak more fully about my own experience, though, which brings me back to the interviewer’s question: “How did you come to have a passion for social justice issues?”

“I believe in social justice because of the Bible.”

Musing on this earlier, I wrote to a friend: “I believe in social justice because of the Bible. I believe in truth telling because of the Bible. I believe in racial and economic justice because of the Bible.”

All those Sunday school lessons and all those Sunday morning and Sunday night sermons, all the vacation Bible schools and all the hymns and choirs planted in me a belief that God loves all creation equally and that while I am a beloved child of God, I am not God’s only beloved. In short, it’s not about me.

Confessions of an idealist

Still, I must confess that I have an easier time declaring my credo around the Bible’s demands for justice than the Bible’s equal demands for forgiveness for those who act unjustly. I struggle to understand how the church of my youth has veered off on a sharper path of exclusion and protectionism and self-interest.

Reflecting on the Union Seminary president’s assessment, I despair to think that the Southern Baptist church today would not have the courage or the desire to form the great social-service institutions they birthed in the early 20th century — the hospitals, the children’s homes, the homes for the elderly. Surely such social action would be shunned for being not evangelistic enough or being subject to anti-discrimination laws or for the misguided notion that everyone ought to be able to pull themselves up by their own bootstraps without any handouts.

Truth be told, I’ve become not just a social justice advocate but an idealist. It frustrates me greatly that so much of American Christianity doesn’t understand, doesn’t want to see, what I see as a clear biblical mandate to action and inclusion.

A lesson from Birmingham

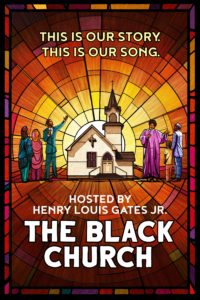

So many things moved me in the recent PBS documentary on the Black church experience. Among the most challenging, though, was the reminder of the Sunday school lesson and sermon text being taught on Sept. 15, 1963, at Sixteenth Street Baptist Church in Birmingham, Ala., when a racist-fueled bomb ended the Bible lesson and the lives of four Black girls.

The Sunday school lesson that morning was from Genesis 45:4-15, about Joseph forgiving his brothers after they sold him into slavery. The sermon to follow was to be from Luke 23:34, where Jesus from the cross asks God to forgive those crucifying him.

The Sunday school lesson that morning was from Genesis 45:4-15, about Joseph forgiving his brothers after they sold him into slavery. The sermon to follow was to be from Luke 23:34, where Jesus from the cross asks God to forgive those crucifying him.

I’d much rather talk about social justice than forgiveness. And yet the Bible teaches both. This is hard. How can the same Bible, the same faith, teach such apparently contradictory ideas? How can we hold these in tension without breaking?

That tension, which is now indeed drawn to the breaking point, illustrates the impasse of American evangelical Christianity today. Two roads have diverged from a common faith, and we are so far down those roads that we see only a faint image of the other in the distance.

People like me feel as though Christians on the rightward path have been lobbing social and political bombs at those who already are marginalized and victimized. My own sense of Christian social justice leads me everywhere except forgiveness. And in that my own heart is hardened, I know.

‘Come home’

Maybe this is wishful thinking, but at my best I keep musing on one of the great old Sunday night hymns from the church of my youth: “Come home, come home; ye who are weary come home.” I want the other “side” of our faith to come home from their agenda, just as I am sure they believe I should come home to their side.

Aren’t we weary of this cultural divide among us? Isn’t there a way to love justice and offer forgiveness at the same time? I don’t know how this all might happen, but I do know this one thing from the old-fashioned faith of my upbringing: It’s not about me, and it’s not about you. It’s got to be about us.

That’s where social justice and forgiveness meet, as we love God with heart, mind and soul and love others as ourselves. Those cannot be separate paths. God help us.

Mark Wingfield serves as executive director and publisher of Baptist News Global.

Related articles:

Isn’t there a third way through our disagreements? | Opinion by Mark Wingfield

Five challenges for the church after this election | Opinion by Mark Wingfield

Making the gospel only about private righteousness is too easy | Opinion by Doyle Sager