When Martin Luther King Jr. wrote his “Letter from Birmingham Jail” in April 1963, I was a sophomore Bible major at a church-related college in the South, studying to become a preacher. None of my professors suggested that I read King’s letter, no one required it, and no one called it to my attention.

In 1957, four years before I enrolled in that college, a significant majority of its students presented the college president with a formal petition, asking the college to take immediate steps to integrate. The president rejected the petition and summarily fired the beloved English professor who had helped the students craft it.

Richard T. Hughes

Two years after I graduated, one of my professors published a book about King. Instead of a Christian, my professor claimed, King was a Communist and an anarchist. Clearly, King and his ideas were not welcome at that school, at least in its halls of power.

In the fall of 1967, I enrolled as a doctoral student in the University of Iowa’s School of Religion. There, King was widely revered, his ideas widely embraced, and students and faculty alike routinely taught and demonstrated on behalf of equal rights for all human beings.

“Much to my shame, I once joined my teenage friends as we drove through an African American neighborhood, hurling racist barbs at people we saw on the street.”

Truth be told, before I arrived at Iowa, I never had given a moment’s thought to questions of racial justice. I was aware of race, of course, but my awareness was shaped by the racial stereotypes that abounded in the West Texas world of my youth, a world that included my church. I learned and thoughtlessly repeated the racist doggerel so common in that world. And much to my shame, I once joined my teenage friends as we drove through an African American neighborhood, hurling racist barbs at people we saw on the street.

That was the world in which I grew up and the world whose assumptions and stereotypes remained largely intact throughout my undergraduate years, even as I trained to become a Christian preacher.

1967: Reading The Autobiography of Malcolm X

My experience at the University of Iowa, however — the protests I witnessed, the lectures I heard and the books I read — began to shatter that world. But my world of racial stereotypes finally came crumbling down when I read The Autobiography of Malcolm X. I had no idea people like Malcolm even existed, and beginning to see the world through Malcolm’s eyes changed everything for me.

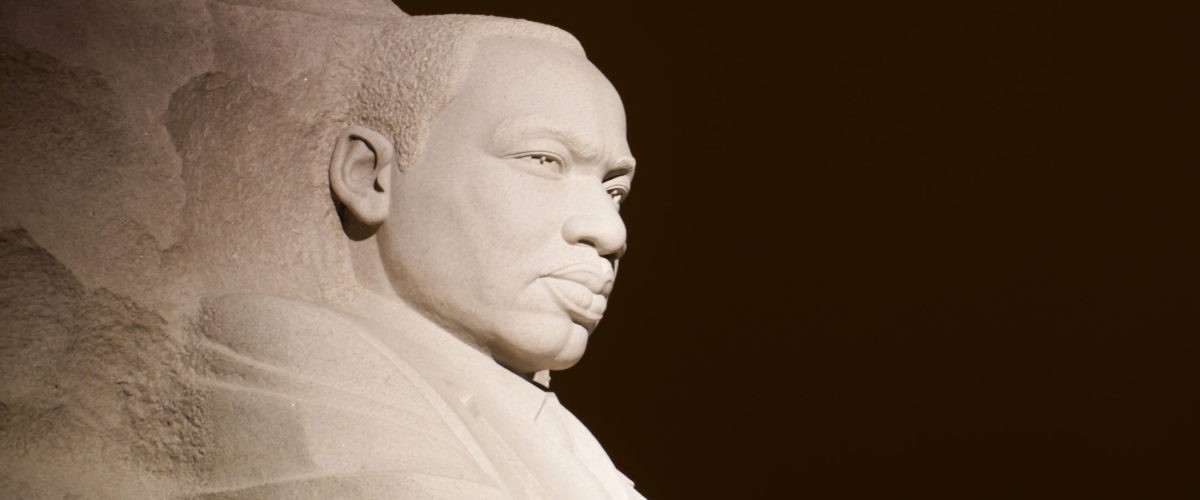

That was the context in which I finally read King’s “Letter from Birmingham Jail,” and as I read, King’s questions about churches in the American South — “What kind of people worship here? Who is their God?” — became my questions, too.

Admittedly, King’s questions had an urgency my questions lacked, an urgency defined by the horrific realities of Jim Crow segregation.

“When you have seen vicious mobs lynch your mothers and fathers at will and drown your sisters and brothers at whim,” he wrote in that letter, “then you will understand why we find it difficult to wait.”

Indeed, according to data compiled by the Equal Justice Initiative, 366 lynchings occurred between 1877 and 1950 in Alabama alone. And yet, the vast majority of the church people in the South, along with their pastors, priests and rabbis, acquiesced to this brutality through their silence or their outright opposition.

“My whiteness had protected me from the suffering and brutality King described.”

That was the context for King’s questions: “What kind of people worship here? Who is their God?”

On the other hand, my whiteness had protected me from the suffering and brutality King described. Still, in the face of what I had witnessed, my questions were real and, for me, immensely urgent. How could I make sense of the devastating truth I had encountered at a major state university — the kind of institutions so many Christians described, and still describe, as “secular” and “godless” — how could I make sense of the fact that I discovered there a commitment to racial justice I never had witnessed at the Christian college I attended during the height of the Freedom Movement?

That question became for me the central question of my life.

Now, in my 81st year, I think I have some answers, thanks to a number of scholars whose insights have illumined my path — James Noel, now deceased but for many years a professor of African American religion and American Christianity at San Francisco Theological Seminary; Michael Emerson, Chavanne Fellow in Religion and Public Policy at Rice University; and Glenn Bracey II, a professor of sociology at Villanova University.

2012: Listening to James Noel

My encounter with Noel occurred in 2012 at the national meeting of the American Academy of Religion in Chicago. My former student who has now become my teacher — Professor Raymond Carr — had invited me to participate in a panel discussion centered on James Cone’s book The Cross and the Lynching Tree.

As a white man, I knew I could make no meaningful contribution to a conversation on America’s “lynching tree,” so I simply explained how the American myths I had learned as a boy had left me vulnerable to profoundly racist perspectives. I spoke of the myths of the United States as a chosen nation, as a Christian nation; as nature’s nation, fully in sync with divine intentions; as the millennial nation, ushering in the golden age for all humankind; and finally, as the innocent nation, free of the guilt that defines the other nations of the world.

When I finished my presentation and sat down at the speakers’ table, James Noel leaned over and whispered, “Professor, you left out the most important of all the American myths.”

“I did?” I asked, surprised at his response. “And what did I leave out?”

“You left out America’s defining myth.”

“You left out,” he responded, “America’s defining myth — the myth of white supremacy.”

After I had taken many months to digest what Noel had said, his simple but powerful comment essentially changed my understanding of race in the United States, much as The Autobiography of Malcolm X had done so many years before. I had understood for a very long time that white supremacists stalked the American landscape, but I always had regarded them as standing on the fringes of American life.

Noel helped me grasp the devastating truth that no white American, including me, would like to admit: The doctrine of white supremacy is, indeed, the defining American myth, the defining component of the American DNA.

In time, I revised my book on the great American myths to reflect that great truth. The revised edition appeared in 2018 under the title Myths America Lives By: White Supremacy and the Stories that Give Us Meaning.

By then I understood the answer to King’s first question, “What kind of people worship here?” They were people for whom the great American myths, especially the myth of white supremacy, had shaped their ultimate commitments far more than anything in the biblical text or any premise of the Christian religion.

2024: Reading The Religion of Whiteness

And then, some 12 years later, the work of two scholars, Michael O. Emerson and Glenn E. Bracey II, entered my life. Their book, The Religion of Whiteness, grew out of a massive research project, funded by a generous grant from the Lilly Endowment, a project in which Emerson and Bracey interviewed in person several hundred people who identified as Christian and several thousand more through carefully constructed questionnaires. Through these efforts, they sought to assess the intersection of race and the Christian religion in the United States. They state their conclusions in the opening chapter.

“Why won’t racism and racial injustice just go away?” they ask. “They won’t go away because race is tangled up with another crucial marker of American identity, religion. That is, race has become ‘religionized’ in the United States; it has taken on transcendent qualities. … We argue — and test the argument with data — that racism and racial injustice have not receded from American life because they are, in good part, the life-giving force of a dominant religion. Put simply, we cannot understand racial injustice without understanding the religion that feeds on racial injustice.”

They call that religion “the religion of whiteness.”

Emerson and Bracey claim that the religion of whiteness has seriously deformed a significant sector of Christianity in the United States.

“The religion of whiteness has seriously deformed a significant sector of Christianity in the United States.”

“White Christians in the United States — our best estimate based on empirical data is two thirds — are faithfully following what amounts to, in effect, a competing religion, or sect, or creed. This religion — the religion of whiteness — distorts people’s Christian commitments and raises race to creedal status over other aspects of historical Christianity. … In short, … we are not merely dealing with interpersonal racism, or material racism, or Christian nationalism, or the Christian Right. These all matter in vitally important ways, and we take them seriously. But we argue that something even larger is occurring. And that ‘something larger’ — that race is ‘religionized’ and how it is so — must be understood before progress can be made.”

Their claim is audacious, to be sure, and would have to square with what we know about the nature of religion to be taken seriously. Many years ago, the noted theologian Paul Tillich argued that what makes something a religion is its ability to speak into the ultimate questions that human beings inevitably raise, cannot help but raise, and those are the questions pertaining to life and death. Many important questions — even urgent questions — never rise to the level of ultimate questions. Whether I graduate this year or next, or whether I take this or that job may be important questions, but questions like these are not ultimate questions.

Tillich argued that only three questions qualify as ultimate questions:

- How can I make sense of death and even overcome it in some meaningful way?

- How can I find meaning in the face of apparent meaninglessness?

- How can I find acceptance — how can I become an acceptable human being — in the face of my shortcomings and my guilt?

The questions of meaning and acceptance are intimately related to the question about death since, apart from meaning and acceptance, life inevitably will spiral toward death. If the religion of whiteness fails to speak to these questions, we can hardly regard it as a religion.

But the religion of whiteness does address these questions, and for people who think of themselves as white, it addresses those questions with decisive power.

In the first place, whiteness provides a sense of almost cosmic acceptance — and thereby addresses the question of guilt — since in the United States and throughout the Western world — and even in some nations where people of color are dominant — whiteness is the norm by which all humans are finally judged. As Emerson and Bracey put it, “whiteness is the imagined right that those designated as racially white are the norm, the standard by which all others are measured and evaluated. It is the imagined right to be superior in most every way — theologically, morally, legally, economically, and culturally.”

“When he promises to ‘make America great again,’ millions of his evangelical followers hear him commit to make America white again, and that, for them, is all that matters.”

It goes without saying that such a powerful sense of rectitude — of belonging to the group by which all other groups are measured and judged — bestows an equally powerful sense of meaning. And while whiteness can hardly overcome death, I know — if I am white — that the community of whiteness will live on long after my own demise, providing me with at least some sense of immortality. In all these ways, then, whiteness does indeed function as a religion.

When I read The Religion of Whiteness, I knew I was reading an important answer to King’s second question which had become my question, too: “Who is their God?”

But there is still more, for in our time, we have witnessed millions of Christians abandon on a stunningly broad scale many of the principles of the Christian religion they claim to profess — truth-telling, sexual purity and basic honesty, for example — in order to protect the whiteness they believe should characterize the American nation.

How else should we make sense of the fact that roughly 80% of American evangelicals have pledged their allegiance to Donald Trump, regardless of the lies he tells, the ledgers and books he cooks, or the women he assaults or brags about assaulting. When he promises to “make America great again,” millions of his evangelical followers hear him commit to make America white again, and that, for them, is all that matters.

These are the modern-day counterparts of the church people of the South in 1963 whose timidity and, in some instances, outright opposition to the Freedom Movement prompted King to ask, “What kind of people worship here? Who is their God?” And like their spiritual forebears of 1963, they, too, have revealed that “the religion of whiteness” they embrace has nothing to do with Jesus.

Richard Hughes is co-author with Christina Littlefield of the forthcoming Christian America and the Kingdom of God: White Christian Nationalism from the Puritans to January 6, 2021. This article is adapted from a chapter in another forthcoming book, Prophet with a Pencil: Essays on King’s Letter from Birmingham Jail, edited by Arthur M. Sutherland, Loyola University Maryland, to be published by Wipf and Stock.