On this day 234 years ago, the U.S. Constitution was signed and sent to the states for ratification, not only proposing a much-needed new system of government but also taking one of the first concrete steps to protect religious freedom.

In 1787, delegates from 12 states met in Philadelphia to create a workable federal government. Over the course of four months, all sorts of issues — large and small — were debated, including religious tests for public office.

Jennifer Hawks

In the 18th century, these tests were exceedingly common in the American colonies and throughout Europe. Most of the original 13 states had some form of a religious test for citizenship or holding public office. Those tests could involve affirming a belief in Christianity generally (Maryland) or in a specific doctrine like the Trinity (Delaware) or specifically limiting elected office to Protestants (Georgia). In fact, eight states today still have a religious test in their state constitutions, although they are no longer enforceable after the 1961 U.S. Supreme Court case Torcaso v. Watkins.

Despite the fact that most of the delegates to the convention represented a state with a religious test for public office, they quickly settled on no need for such tests. They expressed that decision clearly in Article VI with the words “but no religious Test shall ever be required as a Qualification to any Office or public Trust under the United States.”

This provision, however, became a lightning rod in many of the state ratification conventions and sparked much debate on the role of religious tests in a republic.

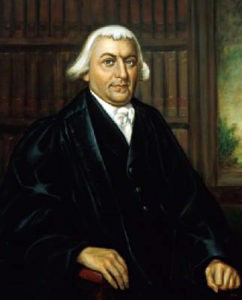

Major General John Sullivan

Some opponents believed a religious test was necessary to weed out the “unworthy” or “immoral.” Others were appalled that this lack of a religious test might mean that one day non-Protestants and even non-Christians would hold federal office. Major General John Sullivan summarized the objections in New Hampshire, writing “even if (the religious test) was given up in all other cases, the President at least ought to be compelled to submit to it; — for otherwise, says one, ‘A Turk, a Jew, a Roman Catholic, and what is worse than all, a Universalist, may be President of the United States.’”

North Carolina delegate William Lancaster argued that this government is being formed “for millions not yet in existence” and that nothing prevents the future generations from electing Catholics or Muslims. He added: “There is a disqualification, I believe, in every state in the Union — it ought to be so in this system.”

James Iredell

The most ardent supporters of Article VI defended it by pointing out that a religious test for federal office undermines religious freedom for all, and that religious liberty should be one of the cornerstones for the new democracy. North Carolina delegate James Iredell praised the ban on religious tests, saying, “I consider the clause under consideration as one of the strongest proofs that could be adduced, that it was the intention of those who formed this system to establish a general religious liberty in America. … How is it possible to exclude any set of men, without taking away that principle of religious freedom which we ourselves so warmly contend for?”

Conceding that opposing the “no religious test” provision was the popular position in Massachusetts, delegate and pastor Daniel Shute declared, “Far from limiting my charity and confidence to men of my own denomination in religion, I suppose, and I believe, sir, that there are worthy characters among men of every other denomination — among the Quakers — the Baptists — the Church of England — the Papists — and even among those who have no other guide, in the way to virtue and heaven, than the dictates of natural religion.”

Today, the inclusion of Article VI seems obvious: Of course, one doesn’t have to pass a religious test to run for public office. Yet, the fierce debate centuries ago shows that this was not the foregone conclusion. Our founders made an intentional choice to break with tradition and laid the foundation for the faith freedom nation they envisioned.

Jennifer Hawks serves as associate general counsel at BJC (Baptist Joint Committee for Religious Liberty), where she provides legal analysis on church-state issues that arise before Congress, the courts and administrative agencies. She is a member of the U.S. Supreme Court, Texas and Mississippi bars.

Related articles:

Barrett nomination renews debate over Constitution’s ‘no religious test’ rule

Senator criticized for asking nominee, under oath, whether he ‘believes in God’