One hot topic — for the church and Americans — is that we as a nation continue to struggle with diversity. Increasingly, folks of all races are moving next door, entering families through marriage or adoption, and sitting next to us in our communities.

And yes, they’re different from us.

Phawnda Moore

They’re different in appearance, dress, lifestyle, faith. It’s said that until we talk about race issues at home, conversations in the church won’t happen. A “101 version of multicultural learning” is desperately needed.

Even if quarantined, let’s talk about other cultures at the dining table, ask questions, process feelings, admit fears and seek solutions. If we lay down some of that resistance and find common bonds, it can lead to a more peaceful coexistence.

My story about this comes from past travels. In retirement, my husband and I are ever curious about the world and its people. We’re inspired by American guides who have relocated to another state or continent and speak positively about their adventure. For example, our guide in Italy was raised in Washington before she settled in the Tuscany region. On a Southwest vacation, our guide lived in Santa Fe, N.M., but had grown up elsewhere in the U.S. Both were open to new places and peoples.

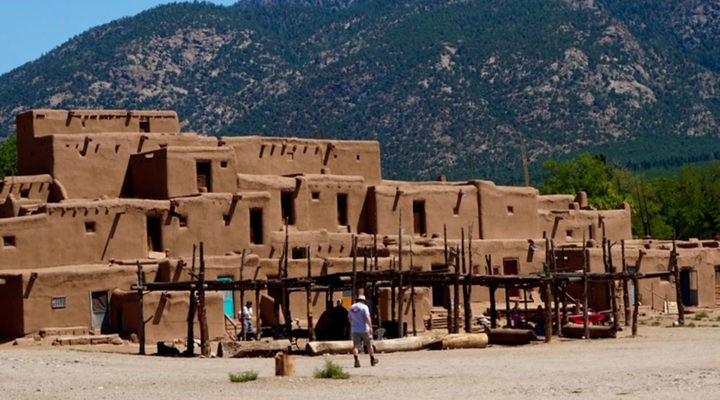

On the Santa Fe trip, there was much to see, learn and do. We stepped down ladders to explore underground kivas, visited weaving galleries, enjoyed a performance of native dancing, learned about amazing eco housing, toured museums, national parks and cultural centers. Not to mention tasting the splendid array of Southwest cooking.

But the highlight I remember the most took place in a local home with a family I almost didn’t meet.

That day we were on the bus, heading out to Tesuque Pueblo for lunch and a lecture in a resident’s home. I hadn’t thought much about this, but as I listened to the agenda, it was different. We were leaving a picturesque area to go to a very primitive, rural community. I quietly grew more attentive when I noticed discarded appliances on the grounds and dismal-looking homes scattered near dirt paths and weeds. The road had become bumpy and dusty, and I was even more concerned when the bus slowed down and then stopped.

That day we were on the bus, heading out to Tesuque Pueblo for lunch and a lecture in a resident’s home. I hadn’t thought much about this, but as I listened to the agenda, it was different. We were leaving a picturesque area to go to a very primitive, rural community. I quietly grew more attentive when I noticed discarded appliances on the grounds and dismal-looking homes scattered near dirt paths and weeds. The road had become bumpy and dusty, and I was even more concerned when the bus slowed down and then stopped.

Oh no, we were getting off here! Our guide directed us to stay together as a group to hike to their home. At this point, I actually considered staying on the bus. This was an adventure I hadn’t expected. It was unknown and unfamiliar, and I probably wasn’t going to like it one bit.

But off we went, a few voicing their thoughts as we walked. No cameras or recordings were allowed at the pueblo. We arrived at a modest dwelling and I thought that maybe I could just politely pass on lunch. The door opened, and a beaming Native American, an educator in his late 50s, welcomed us. Over his shoulder, I saw a long table, set for 40 guests, which filled the entire length of a living room.

I relaxed a little as I surveyed the spotless interior. It seemed almost like Thanksgiving. Although modest, we had everything we needed. Several women made a brief appearance from the aromatic kitchen, smiling shyly as we were seated. Handmade baskets and dolls were displayed on the wall, and I felt an artistic connection.

Sopapillas

The menu was lovely; we were served potato salad, pork cubes and corn, a beautiful, fresh green salad with blueberries, raspberries, strawberries and basil vinaigrette, and iced tea. More courses arrived: sopapilla bread, chicken and beef enchiladas, zucchini and corn. And still more: desserts! Berry pie squares, bread pudding and watermelon. Soon we would learn that our hosts had grown, gathered and prepared this entire feast.

I began to realize that a quiet respect for the earth and its inhabitants literally flourished here. Respect was in the air, in the decor, in all human relationships. Their lifestyle was like a form of prayer.

Then our host again welcomed us for the lecture. We listened to his spirited, personable presentation about life on the pueblo, a community of about 600 Native Americans who trusted each other so much there were no locked doors. Everyone shared the food they grew. They hunted animals for food, not sport. Accountability was expected and enforced. The host was fiercely proud of his community and taught at a local college, giving Powerpoint presentations about the pueblo life, its spirit and faith. He conveyed to us that he was his heritage; they were inseparable but not hostile.

Our traveling companions began asking him questions, and the wonderful lunch was a shared interest. Favorite cookbooks were recommended. He clearly enjoyed teaching and, in response, we were attentive and interested. Our common humanity and unique experiences, although different, enhanced the lively conversation. It worked.

I brought this experience home, humbled by it. The next time I met someone from a different race, I remembered that day; it changed me. I am thankful God showed me God’s own diversity and spirit in others.

“Appreciation is a wonderful thing. It makes what is excellent in others belong to us as well.” — Voltaire, 1694-1778.

Phawnda Moore is a Northern California artist and author of Lettering from A to Z. In living a creative life, she shares spiritual insights from traveling, gardening and cooking. Find her on Facebook at Calligraphy & Design by Phawnda and on Instagram at phawnda.moore