Which can you more likely recite over Sunday lunch after worship: a point from the sermon or a refrain from a hymn?

Congregational singing is a hallmark of Baptist worship, and it’s not just a chance to stand up and stretch, a warmup for the sermon, or an interlude before the offering. The poetry put to music in a good hymn worms its way into our subconscious, and its themes subtly teach our corporate mantra.

And, because so many hymn texts are based on scripture, or at least on theological tradition, we literally sing our faith.

The importance of hymn singing to teach theology and cultivate a worship culture motivated Ken Wilson’s 32-year ministry in music at Knollwood Baptist Church in Winston-Salem, North Carolina.

Ken Wilson

When he came to Knollwood in 1986, children didn’t really know hymns. That mystified Wilson because he grew up singing hymns and knew virtually the whole book. Pondering the difference, he realized that all of his childhood he sang four to five hymns at opening Sunday school assembly, then three to four more in worship Sunday morning, more on Sunday night and Wednesday night, and at youth events. “I sang at least 20 hymns every week of my life, from infancy,” he says. That’s about a thousand hymns a year.

Wilson, who retired in May and moved to Richmond to give his eventual successor a clear flight deck and to be closer to grandchildren, created a schedule to make sure young people at Knollwood learned a similar number of hymns, a process he eventually named “Hymns for a Lifetime.”

It started slowly, simply letting children stay in “big church” through the second hymn, rather than leaving after the first. Then, taking a cue from friend and musician Michael Hawn, he figured out a way to sing with every child in the church every week.

He recreated opening assembly in children’s Sunday school, starting promptly at 9:45 with hymn singing. Teachers were happy to “give up the time” because kids didn’t really arrive en masse until 10. He figured he could do the first verses of 10 hymns in 15 minutes.

And, by the way, kids started getting there at 9:45 so they could sing.

“I didn’t ask the children’s permission,” Wilson recalls. “I didn’t ask if they liked singing hymns, or wanted to sing hymns. I just smiled a lot, and we sang hymns. I was teaching the children that hymn singing is simply what we do at Knollwood.”

Eventually, he created a hymn book with 60 hymns, color-coded in three groups of 20, with the goal to learn 20 hymns each year. Children who memorized 60 hymns in three years became members of the “Hymns for a Lifetime All-Star Team,” with their names engraved on a plaque in the choir room.

Ken Wilson with the ‘Hymns for a Lifetime All-Star Team’ plaque

It became a big deal among the children to be listed on the plaque and each of the 60 names that adorn it strikes a chord of humble pride in Wilson.

Wilson says educators sometimes criticize him for expecting too much of children. But, he thought, first graders can recite 25 radio jingles, so why not infuse that memory power with meaningful music? Little children don’t speak for a couple of years, but they hear from their first breath. “You don’t wait until a kid can read until you teach ’em to talk.”

When you teach a child violin or guitar, you teach them where to put their fingers on the strings before they know the abstract symbols of music. Step by step, Wilson explains.

And the kids love it.

“They cannot wait to sing,” he says. “Each Sunday after we sing hymns, it’s favorite hymn time, and they’re jumping up and down to pick their favorite. No one ever complains about being tired of the same 60 hymns. They know what they love and love what they know.”

Wilson’s program ran first grade through fifth grade, every Sunday morning and every Wednesday night.

As committed as he was to grow a hymn-literate congregation, Wilson never lost sight of the individual singer. One of his proudest moments is his work with seventh-grader James who could not carry a tune “to save his life.” But he loved to sing and never missed youth choir.

Wilson suggested a weekly, four-minute voice lesson. James would melt out of the youth snack supper line and retire to the music room where Wilson would help him match pitch with the piano. It worked so well that when James was a senior, he sang the part of Pharaoh in his high school musical production of “Joseph and the Amazing Technicolor Dreamcoat.”

Adults are amazed when young people sitting next to them sing the hymns from memory.

“Our theology, our call to Christian service and our awareness of God’s presence can all be well expressed in the hymns that we lead our congregations to sing,” Wilson told participants in the 2011 annual meeting of the Hymn Society of the United States and Canada, where he’d been asked to talk about his Hymns for a Lifetime process. “The truths of our hymns become indelibly engraved in our hearts. But this indelible engraving can only take place if our children and youth are taught to sing our hymnic heritage, are led to sing these hymns regularly and to enjoy singing these hymns.”

Wilson taught children more than how to sing the hymns as part of his commitment to passing along the hymnic heritage. Each week he talked with them about some element of hymnology – meter, tune names, composers, hymn writers, form, hymn stories.

“There is no set curriculum to my ramblings,” he says. “Just a sharing of my enthusiasm for hymns.”

Bypassing the pulpit and theological filters

The rich theological basis of most hymns actually gave women the power to preach the gospel – even from pulpits in churches that intentionally denied them the opportunity if they hoped to preach using the spoken word.

“The hymns we sing have the ability to proclaim the gospel,” says Deb Loftis, who retired in 2017 as executive director of the Hymn Society in the United States and Canada. “They do proclaim the gospel, through music, rather than through the spoken word.”

Through music, women have been “preaching” theology through song even when, prevented by tradition and patriarchy, they weren’t allowed to “preach” the spoken word.

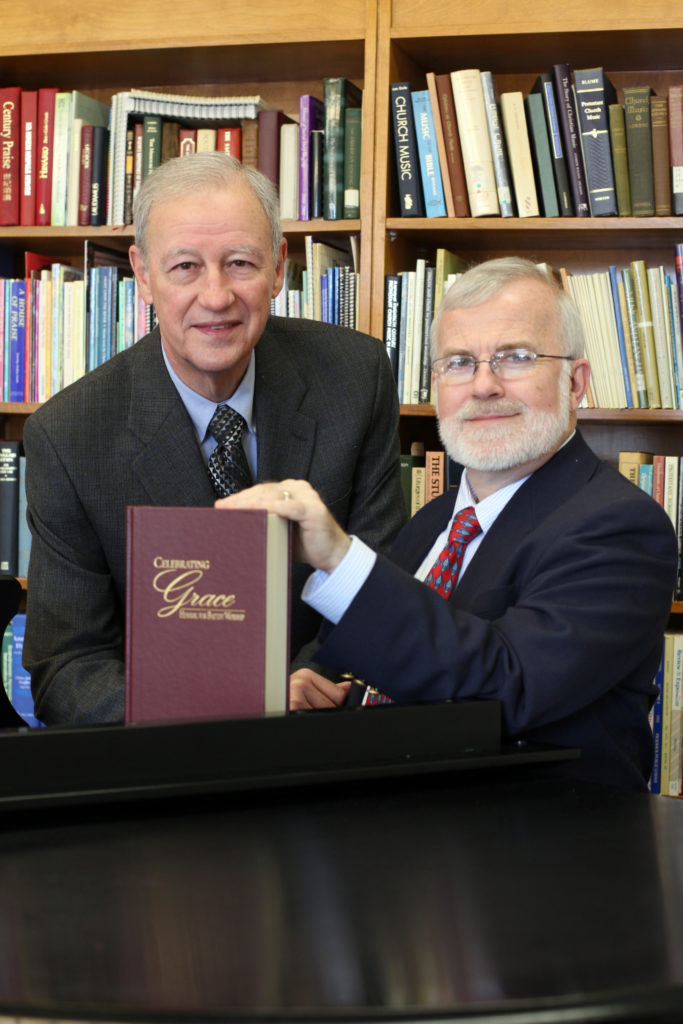

Paul Richardson, recently retired from Samford University, also taught church music at Southern Baptist Theological Seminary in Louisville. He has been friends with Wilson since both they and Loftis were students at Southern.

Women have always been “overused and undervalued” in our churches, he says. His own grandmother, who “called me into ministry,” led music in her church. There are still churches in which women can be hired as a “director of music” but could never be called as “minister of music,” nor could they lead the congregation in singing, because that puts them in a position of authority over men.

Paul Richardson, with Milburn Price, retired dean of the school of music at Samford University

While part of the magic and beauty of hymns is to teach theology in a way that sticks in our minds, “The bad news,” Richardson says, is that “music has a way of carrying things right around our theological filters.”

Caught up in the beauty of the music, we may gloss over text with which we disagree. For instance, when singing the powerful song by Stuart Townsend and Keith Getty “In Christ Alone,” some cringe at the line “On that cross, as Jesus died, the wrath of God was satisfied.” In the Celebrating Grace hymnal, published by Celebrating Grace, Inc., in Macon, Georgia, that line was changed to “as Jesus died, the love of God was magnified.”

The Presbyterian Committee on Congregational Song wanted to make the same substitution in their new hymnal just as they saw it in Celebrating Grace, published in 2010. They said “satisfied” refers to a specific view of theology that it rejects, because it can be interpreted to mean that God killed Jesus.

They could not obtain permission from the authors to make the change, so they did not include the hymn. How it appears in the alternate version in the Baptist hymnal is unclear.

Science of it

Loftis says that music’s ability to convey emotional content helps us to learn and remember.

There is science behind that assumption. Scientifically, setting poetry to music helps to unlock memories stored in your brain’s hippocampus and frontal cortex. Music, with its rhythm and rhyme, provides cues to draw out those memories.

In a story by BBC writer Tiffany Jenkins, autobiographical memory and oral traditions specialist David C. Rubin says music has been an important memory device for thousands of years. In his book, Memory in Oral Traditions, Rubin explains how epic stories like Homer’s “Iliad” and “Odyssey” were passed down verbally using poetic devices. Before the narratives could be written down, they were chanted or sung. Oral tradition depended on memory.

“The hippocampus and the frontal cortex are two large areas in the brain associated with memory and they take in a great deal of information every minute,” Jenkins wrote. “Retrieving it is not always easy. It doesn’t simply come when you ask it to. Music helps because it provides a rhythm and rhyme and sometimes alliteration which helps to unlock that information with cues. It is the structure of the song that helps us to remember it, as well as the melody and the images the words provoke.”

Deborah Loftis, retired executive director of the Hymn Society in the United States and Canada

Loftis, who nurtured the singers and the songs throughout her career, says, “Words and music together are stored in a different place in memory from words alone. So, when you hear a melody the words come along with it.”

When we sing hymns with regularity and repetition, “they become our heart songs,” she says. We know them “by heart.”

“We’ve committed them to memory. These heart songs then can be called upon moments of crisis or joy, where the message will rise almost unbidden to help us.”

Wilson points out that theological ideas are more likely to stick when they are sung as part of a melody than when they are taught verbally. “The singing experience is an emotional experience, and when children learn concepts attached to an experience, it’s with them for a lifetime. You’ve had the experience of hearing a fragment of a song and being transmitted back in time to an event that was important to you.”

Scientists are even studying music-evoked autobiographical memories in patients with acquired brain injuries or who suffer from Alzheimer’s. Think of your own recall of special moments prompted by hearing a snippet from a song popular in your past.

When they analyze brain mechanisms related to memory, scientists find that words set to music are the easiest to remember. How did you learn the alphabet? “A,B,C,D,E,F,G, come along and sing with me.”

That tune-induced recall can comfort people years or decades later during crises.

“I’ve sat with so many families as a loved one is dying to talk about arrangements,” Wilson says. “Before they talk about scripture, they talk about hymns. ‘Can we sing this hymn?’ That’s the first thing that comes to their minds is a scripture that is attached to a melody and harmony.”

Singing our Faith

Wilson has scurried off to Richmond with his wife, Cathy, in retirement to teach classical guitar and to find bands in which to play. In Winston-Salem he was in several bands, each of a different style of music: The Vintage Years Orchestra playing music from the 1920s and 1930s; the Swing Society playing hits from the 40s and 50s; and the Old Dixie Dogs, playing jazz standards.

He was the first classical guitar major at Wake Forest University. The major wasn’t even offered. He was told that to major in church music, he had to concentrate in either keyboard or voice. But he was determined to do it as a guitar major.

When it was time for his first recital, it was as a “piano major,” but on stage, he pulled out his guitar and played the Bach Prelude in D Minor.

Wake Forest hired Robert Guthrie from the North Carolina School of the Arts with one assignment: give this promising classical guitarist lessons.

Thanks to Ken Wilson’s vision, children at Knollwood Baptist Church begin to learn hymns at an early age.

Photo by Stephen Ball

Wilson graduated from Wake Forest, went on to Southern Seminary to earn a master’s in church music and a doctorate in musical arts, always staying with his guitar. His first church was Second Baptist in Richmond, Virginia; then he came to Knollwood in 1986 to serve with the church’s founding pastor, Jack Noffsinger. Consequently, Wilson has served with every pastor at Knollwood, which was founded in 1957.

While there are many online aides for planning congregational worship today, in 1990 Wilson created an early computerized concordance for the Worshiping Church hymnal. After he input the tunes, texts, authors, dates, themes, occasions, first lines, etc., the computer program processed for 10 days before it was ready to print.

If music wasn’t in the church DNA before he got there, it certainly was by the time he left. Knollwood, a medium-sized church, has five singing choirs and four handbell choirs, plus a brass ensemble that meets weekly. Seventy students take guitar lessons each week, two Suzuki teachers work fulltime out of Knollwood, and there are a voice teacher and a piano teacher on site.

But Wilson is jealous for none of that as a “legacy.” He told his choir members to slap themselves if they ever hear themselves start to say to his successor, “When Ken was here, we…”

“Say instead, ‘I really like the way you are doing this.’”

In Richmond, Wilson will also reunite geographically with dear friends Hawn, Loftis and Richardson, all music students together at Southern in the mid-70s.

He leaves behind in Winston-Salem more than a generation of Baptists grounded in the hymnology that teaches, inspires and proclaims their faith.

“I suspect there are adults in all sorts of churches who were able to fit in because of what Ken Wilson grounded them in,” says Richardson. “Whereas many of their peers left the church and weren’t comfortable coming back, Ken made that transition easier.”

Why all the bother?

Wilson loves hymns. He loves church music and he loves children. His Top 10 list of why he developed “Hymns for a Lifetime”:

10. We have a developed culture where children love to sing hymns. They can’t wait to pick their favorites.

9. The children set the stage for hymn singing in worship for the whole church.

8. We have grown a culture where children love to sing hymns in harmony.

7. Children love to be leaders and enjoy the process of learning to be leaders.

6. Children learn that singing hymns are simply fun.

5. Children model the learning and singing of hymns with new styles, new languages, new meters and new accompaniments.

4. One of the goals of the youth choir program is to prepare graduating seniors to confidently and successfully audition for college choirs. Memorizing 60 hymns as a child is a good start toward that goal.

3. Children who memorize 60 hymns have a repertoire of theological language to express joy and find solace during the high and low moments of life.

2. Children who memorize 20 hymns a year, with lots of singing in parts, make very good youth choir members.

1. The No. 1 reason for raising children and youth in a hymn-singing culture is that it becomes very easy for the transforming love of Jesus Christ to become “indelibly engraved” on the hearts of all who sing.

During Wilson’s penultimate Sunday night youth choir rehearsal, one girl raised her hand asking to sing her favorite hymn. “So, we sang it and she just sat there and wept the whole time. There was so much emotion attached to that music and those words.”

For Wilson, being a part of that kind of experience has always been its own reward.

Ken Wilson teaches his young students at Knollwood Baptist Church.

Read more in the Hymns for a Lifetime Series

Photo Gallery: Hymns for a Lifetime

Related commentary at baptistnews.com:

Making God smile through music | Doyle Sager

Too busy to sing? Try anyway | Brett Younger

Related news at baptistnews.com:

Songwriter sees ‘good news’ in declining role of church music

Brian McLaren: It’s time to re-write pro-war hymns

Hymns for a Lifetime is a series about retired music minister Ken Wilson from Knollwood Baptist Church, Winston-Salem, N.C. and the process he used to make sure children and youth are taught to sing hymnic heritage, led to sing these hymns regularly and to enjoy singing these hymns. This series in the “Singing Our Faith” project is part of the BNG Storytelling Projects Initiative. Music is integral to our faith but some individuals and congregations take this expression of ourselves to a new level. In “Singing Our Faith,” we explore this relationship between music and faith and the creative ministers, church leaders and congregations leading the way.

_____________

Seed money to launch our Storytelling Projects initiative and our initial series of projects has been provided through generous grants from the Christ Is Our Salvation Foundation and the Eula Mae and John Baugh Foundation. For information about underwriting opportunities for Storytelling Projects, contact David Wilkinson, BNG’s executive director and publisher, at [email protected] or 336.865.2688.