It was Paul’s women in Romans 16 who finally changed my mind.

I still remember the Sunday it clicked. I was upset after the sermon. So upset that I was doing the dishes. The running water soothed my mind as I scrubbed lunch plates. My husband knew something was wrong (the dishes were a dead giveaway). He walked into the kitchen. He didn’t say anything. Finally, I spoke.

“I don’t believe in male headship.”

Beth Allison Barr

He leaned against the counter. I couldn’t look at him. More time passed, and then he asked, “You don’t believe that men are called to be the spiritual leaders of the home?”

I shook my head. “No.”

He stood there for another minute, and then he just said “OK” and walked away.

I knew he didn’t agree with me then — he had been raised in a complementarian church and attended a complementarian seminary. Yet he was willing to listen and consider a different theological perspective. I am forever grateful for the trust he showed me that day.

It wasn’t actually the sermon that pushed me over the edge, although I do remember it had been about male leadership. What pushed me over the edge was a recent lecture I had given in my women’s history class. We were talking about women in the early church, as we moved chronologically from the ancient world to the medieval world. On a whim, I asked one of the students to open their Bible and read Romans 16 out loud (at a Christian university I can always count on at least one student to have a Bible in hand). I asked the class to listen and to write down every female name they heard.

It was a powerful teaching moment — for the students and for me. I knew women filled those verses, but I had never listened to their names being read aloud, one after the other:

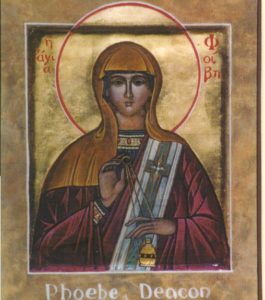

- Phoebe, the deacon who carried the letter from Paul and read it aloud to her house church.

- Prisca (Priscilla), whose name is mentioned before her husband’s name (something rather notable in the Roman world) as a coworker with Paul.

- Mary, a hard worker for the gospel in Asia.

- Junia, prominent among the apostles.

- Tryphaena and Tryphosa, Paul’s fellow workers in the Lord.

- The beloved Persis, who also worked hard for the Lord.

- Rufus’s mother, Julia, and Nereus’s sister.

Ten women recognized by Paul.

Seven women are recognized by their ministry: Phoebe, Priscilla, Mary, Junia, Tryphaena, Tryphosa, and Persis. One woman, Phoebe, is identified as a deacon. Kevin Madigan and Carolyn Osiek write that Phoebe is “the only deacon of a first-century church whose name we know.” Another woman, Junia, is identified not simply as an apostle but as one who was prominent among the apostles.

“Did you know, I asked my students, that more women than men are identified by their ministry in Romans 16?”

Did you know, I asked my students, that more women than men are identified by their ministry in Romans 16? We sat there, looking at the names of those women.

“Why?” a student suddenly interjected, so involved in the lecture she didn’t even raise her hand. “Why have I not noticed this before?”

Probably because the English Bible translation you use obscures women’s activity, I told her, launching into another explanation.

I listened to myself lecturing that day. I listened to myself laying out evidence for how English Bible translations obscure women’s leadership in the early church. I listened to myself as I talked the class through different translations of Romans 16.

Take, for example, The Ryrie Study Bible, published by Moody Press in 1986. My grandfather owned this Bible, and I have his copy on my shelf. Instead of recognizing Phoebe as a deacon, it translates her role as “servant.” Listen to the study note: “The word here translated ‘servant’ is often translated ‘deacon,’ which leads some to believe that Phoebe was a deaconess. However, the word is more likely used here in an unofficial sense of helper.”

“If the phrase ‘a deacon of the church in Cenchreae’ had followed a masculine name, I seriously doubt that the meaning of ‘deacon’ ever would have been questioned.”

“Did you catch that?” I asked my students. No evidence is given for why Phoebe’s role should be translated as “servant” rather than as “deacon.” No evidence is given to explain why the word is more likely used in “an unofficial sense of helper.” We can guess the reason for the translation choice: it is because Phoebe was a woman, and so it is assumed that she could not have been a deacon. If the phrase “a deacon of the church in Cenchreae” had followed a masculine name, I seriously doubt that the meaning of “deacon” ever would have been questioned.

As I taught, I thought about my own church. About how women rarely appeared on stage other than to sing or play an instrument. I thought about how women ran our children’s ministry and men ran our adult ministry. I thought about the time I had been asked to teach an adult Sunday school class, and the pastor had come to look through my material. Since I was just teaching on church history, he let me do it. If I had been discussing the biblical text, though, it would have been a different story.

I remember feeling like such a hypocrite, standing before my college classroom.

Here I was, walking my students through compelling historical evidence that the problem with women in leadership wasn’t Paul; the problem was with how we misunderstood and obscured Paul. Here I was, showing my students how women really did lead and teach in the early church, even as deacons and apostles.

Junia, I showed them, was accepted as an apostle until nearly modern times, when her name began to be translated as a man’s name: Junias. New Testament scholar Eldon Jay Epp compiled two tables surveying Greek New Testaments from Erasmus through the 20th century. Together, the charts show that the Greek name Junia was almost universally translated in its female form until the 20th century, when the name suddenly began to be translated as the masculine Junias.

Junia, I showed them, was accepted as an apostle until nearly modern times, when her name began to be translated as a man’s name: Junias. New Testament scholar Eldon Jay Epp compiled two tables surveying Greek New Testaments from Erasmus through the 20th century. Together, the charts show that the Greek name Junia was almost universally translated in its female form until the 20th century, when the name suddenly began to be translated as the masculine Junias.

Why? Gaventa explains: “Epp makes it painfully, maddeningly clear that a major factor in 20th-century treatments of Romans 16:7 was the assumption that a woman could not have been an apostle.” Junia became Junias because modern Christians assumed that only a man could be an apostle.

As a historian, I knew why the women in Paul’s letters did not match the so-called limitations that contemporary church leaders place on women. I knew it was because we have read Paul wrong. Paul isn’t inconsistent in his approach to women; we have made him inconsistent through how we have interpreted him. As Romans 16 makes clear, the reality is that biblical women contradict modern ideas of biblical womanhood.

I knew all this. Yet I still allowed the leaders of my church to go uncontested in their claim that women could not teach boys older than 13 at our church. I still remained silent.

I continued my lecture. The historical reality is the same for Phoebe, I told my students. Paul calls her a deacon. No one disputes the text — they can only dispute the meaning of the text. Phoebe was recognized as both a woman and a deacon by early church fathers. Origen, for example, wrote in the early third century that Phoebe’s title demonstrates “by apostolic authority that women are also appointed in the ministry of the church, in which office Phoebe was placed at the church that is in Cenchreae. Paul with great praise and commendation even enumerates her splendid deeds.”

I continued my lecture. The historical reality is the same for Phoebe, I told my students. Paul calls her a deacon. No one disputes the text — they can only dispute the meaning of the text. Phoebe was recognized as both a woman and a deacon by early church fathers. Origen, for example, wrote in the early third century that Phoebe’s title demonstrates “by apostolic authority that women are also appointed in the ministry of the church, in which office Phoebe was placed at the church that is in Cenchreae. Paul with great praise and commendation even enumerates her splendid deeds.”

While we can certainly question what Origen meant by the “ministry of the church,” it is clear that Origen accepted Phoebe’s appointed role. A century later, John Chrysostom, the “golden-tongued” preacher, wrote of how great an honor it was for Phoebe to be mentioned “before all the others,” called “sister,” and distinguished as a “deacon.”

“Both men and women,” concludes Chrysostom, should “imitate” Phoebe as a “holy one.” In his homily on 1 Timothy 3:11, Chrysostom makes it clear that he understands women to serve as deacons just as men do. As he writes, “Likewise women must be modest, not slanderers, sober, faithful in everything. Some say that (Paul) is talking about women in general. But that cannot be. Why would he want to insert in the middle of what he is saying something about women? But rather he is speaking of those women who hold the rank of deacon. ‘Deacons should be husbands of one wife.’ This is also appropriate for women deacons, for it is necessary, good, and right, most especially in the church.”

A woman depicted at prayer in an ancient Christian mosaic seen in the Vatican’s Pio Cristiano Museum. (Wikimedia Commons/Miguel Hermoso Cuesta)

If this frank understanding of female leadership by a fourth-century presbyter and deacon surprises you, church historians Madigan and Osiek remind us that it shouldn’t: “In John’s churches in Antioch and Constantinople,” they write, “female deacons or deaconesses were well known.” Describing Phoebe as a deacon wasn’t surprising to Chrysostom because some of his good fourth-century friends were female deacons. Indeed, Madigan and Osiek have uncovered 107 references (inscriptions and literary) to women deacons in the early church.

Of course, I told my students, not everyone in the early church supported women in leadership. The office of presbyter testifies loudly to how patriarchal prejudices of the ancient world already had crept into Christianity. Remember how Aristotle considered the female body to be monstrous and deformed?

Ecclesiastical leaders imported these ideas into their council decisions, declaring as early as the fifth century that female bodies were unfit for leadership. As Madigan and Osiek write, “Cultic purity becomes associated with males, impurity with females. This was the biggest argument against women presbyters.”

By the sixth century, while the church was moving across the European landscape and replacing the old secular seats of Roman power with the sacred offices of bishop and priest, women also were on the move, back into their prior place under the authority of men.

“Dr. Barr, why don’t they teach us this in church?”

I looked at the student, my heart twisting. Most people simply don’t know, I said. Seminary textbooks are often written by pastors — not by historians (and especially not by women historians). Most people who attend complementarian churches don’t realize that the ESV translation of Junia as “well known to the apostles” instead of “prominent among the apostles” was a deliberate move to keep women out of leadership (Romans 16:7). People believe that women were banned from leadership in the early church just as they are banned from leadership in the modern church. The church teaches what it believes to be true.

These were the things I said out loud.

What I didn’t say — and what made the tears roll down my cheeks as I stood in front of my sink that day — was that I knew the truth. I knew the truth, and still I stayed silent at my church.

“I stayed silent because I was afraid of my husband losing his job.”

I stayed silent because I was afraid of my husband losing his job. I was afraid of losing our friends. I was afraid of losing our ministry.

Complementarianism rewards women who play by the rules. By staying silent, I helped ensure that my husband could remain a leader. By staying silent, I could exercise some influence. By staying silent, I kept the friendship and trust of the women around me. By staying silent, I maintained a comfortable life.

Except I knew the truth about Paul’s women. I knew the reality that women who are praised in the Bible — like Phoebe, Priscilla and Junia — challenge the confines of modern biblical womanhood.

As a historian, I knew that women were kept out of leadership roles in my own congregation because Roman patriarchy had seeped back into the early church. Instead of ditching pagan Rome and embracing Jesus, we had done the opposite — ditching the freedom of Christ and embracing the oppression of the ancient world.

I turned the water off in the sink and stacked the dishes.

It was time for me to stop being silent.

Beth Allison Barr serves as professor of history and associate dean of graduate studies at Baylor University. She earned a bachelor of arts degree from Baylor University and a master of arts and Ph.D. in Medieval history from the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. This column is excerpted from her new book, The Making of Biblical Womanhood, ©2021, and is used by permission of Baker Publishing.

Beth Allison Barr serves as professor of history and associate dean of graduate studies at Baylor University. She earned a bachelor of arts degree from Baylor University and a master of arts and Ph.D. in Medieval history from the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. This column is excerpted from her new book, The Making of Biblical Womanhood, ©2021, and is used by permission of Baker Publishing.