Humanizing the poor and hungry is a vital first step for individuals and churches called to combat poverty and hunger, a group of Cooperative Baptist Fellowship ministers and lay leaders learned during a recent webinar hosted by CBF Heartland.

“It’s important for us to visualize and put a face with the kind of folks we work with,” said Jason Coker, field director of Together for Hope, the Fellowship’s rural development coalition. He and Nicole Stringfellow, regional vice president of the coalition’s Delta Region in Mississippi, were co-presenters during the virtual “Advocacy and Poverty” session.

Nicole Stringfellow

Coker and Stringfellow avoided sharing one-size-fits-all ministry ideas and instead opted to devote their comments and role-playing breakouts to offer glimpses into the desperation and dilemmas that plague families trapped in poverty and hunger.

They examined stereotypes about the poor that divide the suffering into those deserving and underserving of help, and they delved into statistics designed to present the immensity of the problem, evoke empathy and inspire action.

“Start thinking about the information Jason provides as well as your own assumptions because these are real-life stories,” Stringfellow said. “And think about what roles you and the church can have in this work.”

Coker began with one hard-hitting statistic about poverty — that children and the elderly comprise 30% of Americans oppressed by food and financial insecurity.

Jason Coker

“We don’t usually think of children and we don’t generally think of senior adults when we think of poverty, and that has direct implications for our lack of involvement in advocacy work as it relates to poverty,” he said. “So anytime you hear about poverty, I want your children to come to your mind and I want your grandparents to come to mind.”

For emphasis, he added that 12 million children in America live below the federal poverty line. “That’s one in six kids,” Coker said.

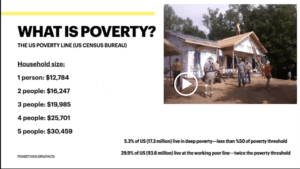

The federal government’s definition of poverty is based on annual income. Currently, that threshold is an annual income of $12,000 or less for individuals and just a few thousand dollars more for couples and those with children.

“Let that sink in for just a little bit and think about the things in your house,” Coker said. “What would it take for you to live on $12,000? That’s $1,000 a month, basically. The poverty line for two people is $16,247, … for two parents with one child, it’s $19,985.”

And there are those who subsist on much less, he added. “The terrible thing is that 5.3% of the U.S. population — that’s 17.3 million people — live in deep poverty, which is 50% of those (previous) numbers. That’s a person living on less than around $6,000 a year and two people living on about $8,000 a year.”

And there are those who subsist on much less, he added. “The terrible thing is that 5.3% of the U.S. population — that’s 17.3 million people — live in deep poverty, which is 50% of those (previous) numbers. That’s a person living on less than around $6,000 a year and two people living on about $8,000 a year.”

The working poor typically toil at multiple minimum-wage jobs while suffering through hunger and poverty, he added. “Almost 30% of America lives at the working poor line. … They work as much as they can and yet they are still living right there at the working-poor threshold.”

Then there are American attitudes to overcome, he said. Impoverished people are judged as undeserving of assistance, from the government or churches, if they are not working, dress differently, have children out of wedlock or appear to abuse government programs. These and similar attitudes directly affect “the way we engage in advocacy.”

“Anytime you hear about poverty, I want your children to come to your mind and I want your grandparents to come to mind.”

The role-playing scenarios attempted to demonstrate the complexity of factors that conspire to send families below the poverty line and keep them there. One scenario focused on a single father trying to raise a son while out of work due to a botched surgical procedure.

Stringfellow challenged participants to imagine government and church programs that could help someone in that situation.

“We want you to look at what can be done immediately to help the household, what policies impact households such as this and what advocacy work can be done by the church and by individuals,” she said. “And remember, this is not Monopoly — we’re not going to just throw money at the situation.”

Jeff Langford

CBF Heartland Coordinator Jeff Langford, who moderated the discussion, said the presentation was taken to heart. “We think that finding ways for churches and leaders to connect around common areas of concern is absolutely vital.”

The information shared during the webinar also landed on a personal level, Langford said.

“I am pretty insulated from the real challenges of persistent poverty, so I have as much to learn as anyone,” he said. “But I came away from the webinar feeling hopeful that people of faith can make a difference in people’s lives — if we decide it’s important enough. I am more convinced than ever that Together for Hope practitioners and other experienced professionals can help churches serve their communities more effectively.”

Related articles:

Together for Hope partnership steps up the drive for hunger relief in Mississippi

What can we learn about poverty from those who work along the Texas-Mexico border?

At the center of Arkansas Delta’s fight against poverty and division: an 85-year-old swimming pool