At twilight, a few hundred community members gathered in the church parking lot for a prayer vigil. Just a few days before, a senseless incident of road rage cast our city into grief.

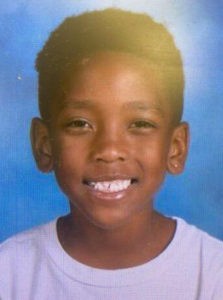

A young mother was driving home late at night with her three children — ages 7, 6 and 1. In the darkness, she admitted to something we all have done, inadvertently cutting off another driver. The response was a sudden flash shattering the darkness. Behind that flash was a bullet that struck her 7-year-old Zakylen, nicknamed Ky. Frantic in the face of this violence, this mother immediately pulled off the four-lane road and dialed 911. In minutes EMTs transported Ky to the hospital, where he was pronounced dead.

Jay Robison

Ky was a young boy whose bright and broad smile lit up any room when he entered. Police officers who responded to the scene became physically ill by the carnage they saw that night. Our community was gripped by outrage at this random act that took someone so young; but also, the realization that this event could have happened to anyone of us.

At the vigil, those gathered wondered how that mother could ever drive a car again. Our community cried for a 6-year-old sibling who would have the horror of that scene engraved on his mind for the rest of his life. We were in grief for an infant who never would know his brother except through the memories of others.

We assembled for that vigil drawn together by our grief and questions. Several police officers were in uniform. The mayor spoke, trying to offer words of comfort to those in attendance. My friend Reggie is Ky’s pastor. He told about Ky being in church a Sunday or two before his murder. Members of his church passed through the crowd sharing candles and water. In addition, they handed out some of Ky’s favorite treats, which had the message Ky had often repeated affixed to them, “I am going to go to the beach for my birthday!”

As we wrestled with our communal grief, I marveled at the expression of faith present. Family members addressed the crowd, telling stories about of Ky’s giving spirit. I pondered how I might respond to such an unthinkable tragedy.

“I pondered how I might respond to such an unthinkable tragedy.”

Many Christians would want to argue with God over why something so terrible could happen to them. Their outrage at the injustice would be palpable. I recognize my own way of thinking in this response. After all, if we are faithful to God, isn’t God required to reward our faithfulness? When we come to God with a sense of privilege, we bring expectations as well. God owes us something because, after all, we have been the righteous ones.

That evening in the shadow of that church, I saw a different expression of faith. The grief and pain were evident. However, the sense was not that God had abandoned them in their pain but that God had joined them in their pain.

I was reminded of a powerful excerpt from Elie Wiesel’s book Night. The scene is before the gallows. Two men were no longer alive. A third rope was still moving: the child, too light, was still breathing. He remained in a struggle between life and death right before everyone’s eyes. It was a horrific sight. Wiesel heard someone in the crowd ask the question which has no doubt crossed everyone’s mind: “For God’s sake, where is God?” And from within him, Wiesel said, he heard a voice answer: “Where is he? This is where — hanging here from these gallows.”

Jesus said, “Blessed are those who mourn, for they will be comforted.”

Zakylen Greylen Harris

I left the vigil reflecting on James Cone’s book The Cross and the Lynching Tree, in which he discusses how differently white and Black Christians experience tragedies like the one that drew me to the prayer vigil. Cone suggests, or at least I surmise that he does, that when tragedy comes to whites who have benefitted from privilege, they cry out, “How could this happen to me? I am a good moral person.” Cone says white Christians argue, “Suffering and death were not supposed to happen to the Messiah. He was expected to triumph over evil and not be defeated by it.” God controls everything that happens.

Black Christians, on the other hand, recognize the presence of a God who died on a Cross as a life-giving affirmation of comfort and God’s presence. God did allow Jesus to be crucified on the Cross. As a result of that reality, Ky’s family could speak of God’s presence even in the face of such an unspeakable tragedy.

God identifies with the fallen and the hurting. The spirituals acknowledge terrible struggles but also affirm God’s liberating-with-us presence catching our tears. There is a depth of faith that I as a privileged white male living in America need to allow to grow in my life with the water of my tears in the face of injustice and suffering.

Jay Robison serves as pastor of Cornerstone Baptist Church in Valdese, N.C.