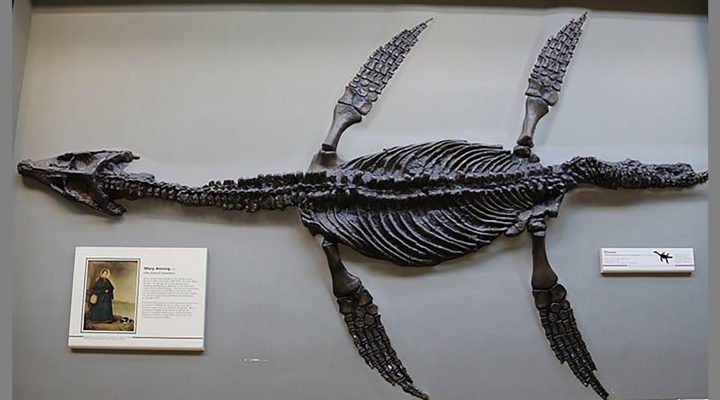

People living along England’s Dorset coast had long scavenged fossils dislodged from local cliffs. But everything changed in 1811 when young Mary Anning and her brother Joseph found a 4-foot-long skull of an unknown ancient beast.

The two youngsters soon uncovered an entire skeleton of what is now known as an Ichthyosaurus. Their discovery of this prehistoric 10-foot lizard fish was just the beginning of six decades of awe-inspiring scientific discoveries and wrenching theological debates that changed Britain and the world.

Historian Michael Taylor’s lively book, Impossible Monsters: Dinosaurs, Darwin, and the Battle Between Science and Religion, gives a rich, detailed study of “the first period in human history where new knowledge of the earth and its prehistoric inhabitants collided seriously and persistently with Christian belief in the accuracy of the Bible.”

Historian Michael Taylor’s lively book, Impossible Monsters: Dinosaurs, Darwin, and the Battle Between Science and Religion, gives a rich, detailed study of “the first period in human history where new knowledge of the earth and its prehistoric inhabitants collided seriously and persistently with Christian belief in the accuracy of the Bible.”

Published in time for next year’s 100th anniversary of the Scopes “monkey” trial, Taylor’s study leads readers through similar conflicts that convulsed the century before Scopes.

After the Ichthyosaurus find, Britain’s caves, fields and marshes gave up huge ancient skeletons, unleashing “the consequent revolutions that took place in science, religion and society” that brought about a “Victorian crisis of faith.”

Why Britain? Britain’s industrial revolution saw humans furiously digging quarries, canals and mines that upturned many surprising fossils. Britain’s history of scholarship and its early forays into what we now call science meant ancient bones were preserved and carefully studied.

By 1870, the paleontology action shifts to the American West, thanks to expeditions funded by Yale University. Scientists soon would unearth skeletons of T Rex in Montana along with other dinosaur monsters from America’s badlands.

Eighteenth-century Britain was a “deeply and sincerely Christian place” where Anglicans controlled government, press and speech while enjoying privileges denied to Catholics and dissenting Protestants, such as holding public office or graduating from university.

Anyone who publicly questioned Christian orthodoxy could be thrown in prison for blasphemy or apostasy, leading many scholars to conceal or delay publishing their findings. Charles Darwin first published studies from his five-year voyage on the Beagle in 1839 but would wait 20 years to publish On the Origin of Species.

Many of the earliest geologists were believers or even Anglican clergy who sought to harmonize new discoveries with traditional religion. William Buckland told enraptured audiences that “geology had come not to bury religion but to praise it.”

Icthyosaur drawing

But others were convinced there could be no harmony between religion and the emerging sciences of geology, stratigraphy and paleontology. One clergyman called geologists “a secret society dedicated to the overthrow of the established order.”

The naysayers cited conflicts on a range of issues that threatened to “remove divine agency from the natural history of the world”:

- The age of the earth. Irish archbishop James Ussher combined biblical and secular sources to compile his chronology, published in 1650, which concluded God created everything in October of 4004 B.C. By 1679, Ussher’s chronology was published in Bibles, leading many to assume his young earth dating scheme was “biblical.”

- The means of creation. Is Genesis a scientifically accurate description of God’s creation of the cosmos and all living things in seven 24-hour days? Or is everything old enough to allow plenty of time for natural mechanisms to alter the earth and its species?

- Humankind’s relationship to other species. Are we not made in God’s image? As Taylor writes, “Were humans truly and innately superior or were they merely the most advanced among myriad forms of life?”

- Implications of extinction. The idea that there were many creatures who went extinct “was thought to verge on blasphemy” because Genesis says Noah took pairs of every clean animal onto the ark and that all land species had survived. But dinosaur fossils revealed extinct creatures way too large for any ark.

- Did God err at the moment of creation? “How could animals improve on what was already perfect?”

Scientific questions also raised social questions, as Taylor notes: “If nothing but evolution separated humankind from brute animals, what was there naturally to separate the ruling classes from the masses?”

As scientists were examining ancient bones, Britain saw a rising tide of secularism: Thomas Huxley coined the term “agnostic;” England saw its first atheist journal; German higher criticism raised additional questions about the Bible’s reliability; and Parliament passed a bill ending the taxes that had funded Anglican churches and clergy.

“The conflict between these two great fonts of authority led me, even as an 8-year-old, to ask questions.”

These issues are personal for Taylor, who attended a school in “the Ulster Bible belt” not far from where Irish archbishop James Ussher compiled his annals. Taylor realized early on that his “fascination with dinosaurs” conflicted with his literalist upbringing.

“At primary school in Northern Ireland, teachers taught me that God had made the world in six days, 6,000 years ago. … The conflict between these two great fonts of authority led me, even as an 8-year-old, to ask questions,” he writes.

In a book that’s as engaging as Richard Holmes’ The Age of Wonder: How the Romantic Generation Discovered the Beauty and Terror of Science, Taylor deftly shows how the conflict led to “religion’s concession of supremacy.”

“Christianity could no longer command automatic or exclusive authority in public life, and the verses of the Scriptures no longer formed the essential core of knowledge with which many Britons approached questions of morality, politics and especially science,” he writes. “Few if any transformations in intellectual history have been more profound.”

Today, public opinion on origins remains divided, according to a July Gallup poll:

- 24% (a new high) of U.S. adults say humans evolved from less advanced forms of life over millions of years without God’s involvement

- 34% harmonize creation and evolution, saying humans evolved with God’s guidance

- 37% say God created humans in their present form within the past 10,000 years, but this is a new low for this view.