There are no easy days for migrants stranded in Mexico while seeking asylum in the United States.

The challenges they face are treacherous and seemingly limitless, including the constant threat of kidnappings and murder by prowling cartel members, gnawing hunger and poverty, exposure to the elements and the emotional trauma of leaving behind homes, families and communities to escape the brutal violence and economic hardship in their native countries.

But there are, here and there, oases of hope and safety for asylum seekers languishing in Mexico: migrant shelters operated by humanitarian and religious organizations, many of which are financially and materially supported by Fellowship Southwest.

Anyra Cano

“The people staying here are very fortunate. Many others have been kidnapped or killed or separated from their children along the way,” said Anyra Cano, head of programs and outreach for Fellowship Southwest, an independent, ecumenical ministry founded by the Cooperative Baptist Fellowship in 2017.

Members of the Baptist News Global board of directors recently convened in El Paso and got a briefing on the situation at the U.S.-Mexico border from Cano, Fellowship Southwest leader Stephen Reeves, and Rosalio Sosa, an El Paso pastor who supports work in 19 immigrant shelters on both sides of the border. Then the group traveled across the border to Palomas, Mexico, to see firsthand the humanitarian work going on there.

Visitors to the community of 7,000 residents — located just over the border from Columbus, N.M. — are greeted by a statue of Pancho Villa, the Mexican revolutionary who in 1916 led a raid on Columbus.

Not far from that memorial, Fellowship Southwest supports the Tierra de Oro shelter, part of a network of shelters led by Sosa.

The 52 migrants staying in the modest metal building that day included toddlers, youth and young adults. Cano said they all were lucky to be alive.

“Not having places like this puts migrants in danger and their children in danger,” she said. “Places like this also protect the young girls and women from human trafficking. I don’t know how you can measure that.”

Pastor Sosa outside the shelter.

This shelter is located in a neighborhood notable for its dirt streets, stray dogs and numerous dilapidated or unfinished homes and businesses. Like another four shelters Sosa operates in the teeming city of Juarez two hours to the east, the facility routinely houses dozens of migrants, many of whom have endured months-long, perilous journeys from Nicaragua, Venezuela, Colombia, Guatemala, Haiti and other nations beset with political persecution, gang violence and decimated economies.

Not all are “poor” in the economic sense of the word; many drove their own vehicles or rode commercial buses to flee their hometowns and arrive in Palomas. But all have left behind whatever they had to seek safety in the United States and hopes of starting new lives.

“This is the safest we have felt. We are a long way from home.”

“This is the safest we have felt. We are a long way from home,” said a Columbian woman who also has a 5-year-old son.

Despite the shelter’s proximity to the border, the woman and most of her fellow migrants are also a long way from safety in the United States, Pastor Sosa said. “The people here are waiting hearings in the U.S. There are many families and kids. Some stay as long as seven months as they try to get to the U.S. legally.”

Those stays are made possible in part by funds from Fellowship Southwest, Sosa said. “We can feed a lot of people with what they give us. This is important because we don’t want to leave anyone in the streets with all the kidnappings and violence.”

Mafia-like cartels are a way of life in Mexico and parts of Central America. They threaten, harm, kidnap and murder people in order to retain power and to fund their operations. Everyone living in this shelter has a story of terror to tell.

A Honduran man whose brother was killed by gangs said his mother found the shelter on Facebook and called Pastor Sosa for help.

“The gangs (in Honduras) threatened to kill our family unless we pay their tax. We are too scared to return to Honduras,” the man explained.

“Being in Mexico, trying to get into the U.S., is not what we want. But because of all the violence we have no option but to flee.”

A Colombian man emphasized that migrating to the U.S. is no one’s first choice: “Being in Mexico, trying to get into the U.S., is not what we want. But because of all the violence we have no option but to flee.”

A 22-year-old migrant from Southern Mexico described a cartel shooting that left her in a wheelchair and caused her and her family to migrate. The shooting was an attempt to murder her entire family.

This young woman has an uncle and aunt who live in Juarez and have been so moved by their volunteer work at the shelter that the aunt quit her full-time job in order to volunteer more at several of the shelters.

A man from central Mexico endured the murder of his son, kidnapping of his nephews and arson of his home before attempting to seek asylum in the United States. “We are having these problems again and we are on the run,” he said. “It’s why we are asking you to help us.”

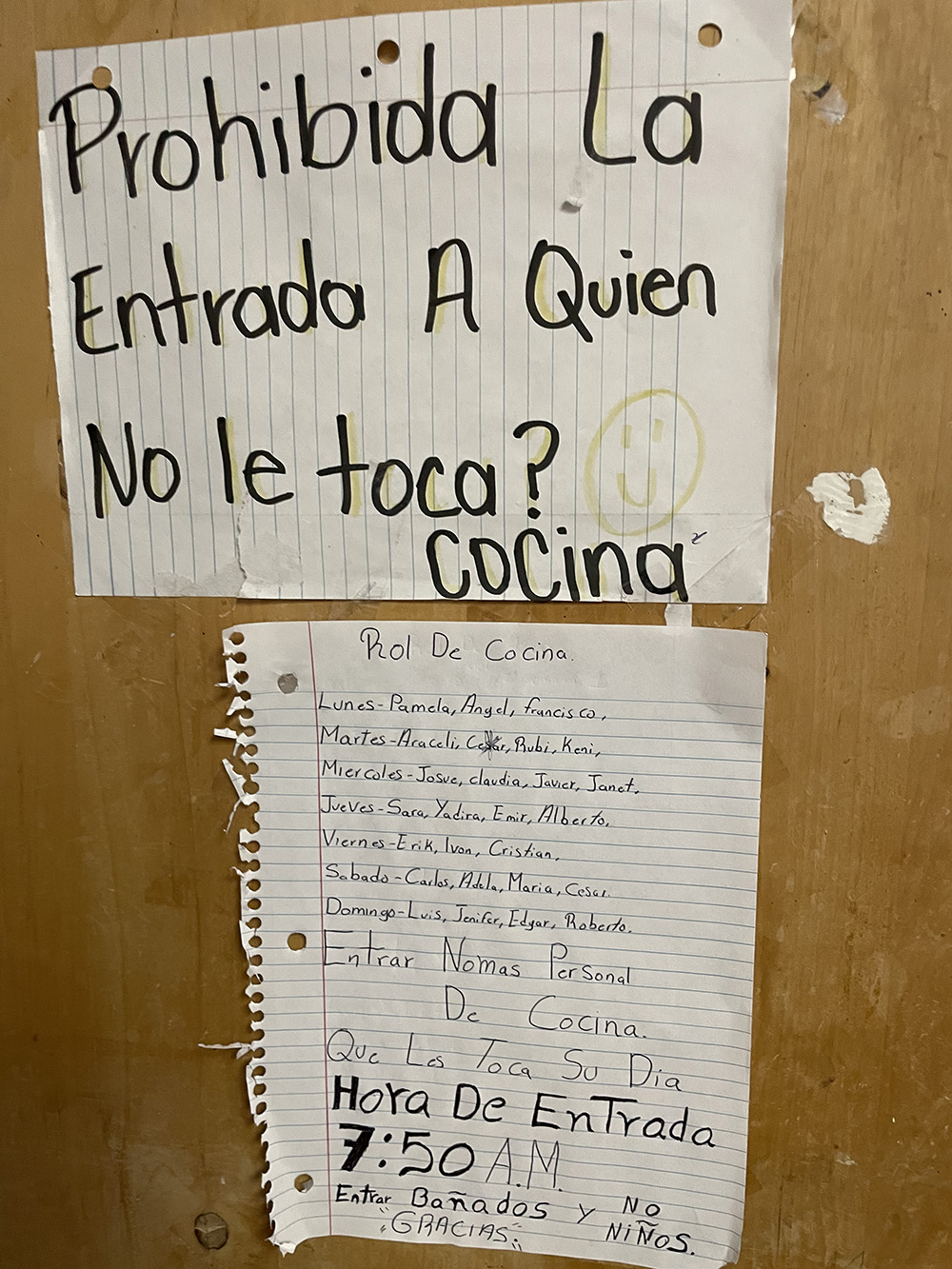

The kitchen at the shelter.

There are no employees at the shelter, Pastor Sosa explained. Everything is done by those living in the shelter. Weekly schedules are posted on the walls for kitchen duty, cleaning duty, teaching children, laundry, child care and other tasks. Sosa and his wife bring in groceries once a week. It is a joy to shop for these new friends, most of whom cannot risk stepping outside the shelter compound, the pastor said.

The day of the BNG board’s visit was Pastor Sosa’s birthday. Shelter residents had arranged to surprise him with a birthday cake, balloons and a banner.

A duty list posted on the kitchen door at the shelter.

Against the stereotype most Americans have of those seeking asylum in the United States, residents of the shelter are not illiterate, poverty-stricken people, Sosa explained. “Many of them are well educated, including doctors and lawyers.”

Fellowship Southwest Executive Director Reeves said the need for such places of refuge will not diminish any time soon due to the brokenness of U.S. immigration policy, which includes the Biden administration’s continued use of the Trump-era Title 42. That policy is used to return tens of thousands of asylum seekers from the U.S. border to Mexico to await adjudication of their cases.

The Biden White House recently rolled out CBP One, a mobile app immigrants now are required to use to apply for appointments to make asylum claims. The president touted the application as a way to reduce illegal border crossings and to bring order to the asylum process. But the reality is the system is so overloaded that it takes weeks to get through to submit asylum applications, migrants at the shelter said.

“We do it every single day,” one woman from Southern Mexico said. “We are aware of only one family who successfully submitted an application.”

Cano, who grew up in El Paso but now lives in Fort Worth, Texas, acknowledged that visiting the shelters and assisting there can be emotionally challenging at times, especially because of the children involved.

“I ask God not to make me immune from the stories and to remember that each person here is a story.”

“I get through that with prayer,” she said. “I ask God not to make me immune from the stories and to remember that each person here is a story. I think of my (2-year-old) daughter and what I would want for her. My parents were also immigrants. I just do not want to become cold to the stories, and to remember that I’m human and it’s OK for me to hurt for them.”

BNG Executive Director Mark Wingfield, who was part of the group, wrote his weekly Friday Roundup about the shelter in Palomas and the hope of Pastor Sosa to vacate the rundown city-owned building and occupy a shelter to be constructed on donated land 22 miles down the highway in a community called La Modelo.

The first phase of that planned construction will house up to 150 people. Sosa said he didn’t know where the money would come from to build the new facility but he believes God will provide.

BNG board members listen to Pastor Sosa explain his vision for the new shelter on this dusty piece of land.

At a debriefing dinner that night back in El Paso, members of the BNG board wondered if they and others they know could be the answer to the pastor’s prayers. When Wingfield wrote about this need in the Friday Roundup, he called on BNG readers to join him in giving the funds necessary for construction.

“As much as BNG needs and wants your financial support, I want to ask you to give your money somewhere else first,” he wrote. “Pastor Sosa is praying for God to send the money that would allow him to build a new and better shelter for immigrants in Palomas. We can be the answer to his prayers.”

Within the first two days of that appeal, BNG readers already had donated more than a third of the anticipated costs of construction, and Wingfield said he believes readers and their churches will come through with the full amount, which is anticipated to be between $40,000 and $50,000.

Contributions may be given through the Knox Fund for Immigrant Relief, named for Fellowship Southwest founder Marv Knox, who also is a former BNG board member and frequent BNG contributor.

Related articles:

Fellowship Southwest becomes independent, ecumenical ministry

Fellowship Southwest adds immigration legal aid component

Title 42 is expelling the good people, not the bad people, border advocate explains