Netflix is angry about account sharing, seeing the practice as an unfair, under-the-table raid of its revenue.

But in devout, fiercely Pentecostal Zimbabwe — where joblessness is deep and inflation is, according to John Hopkins University, at a frightening 487% — a thriving “under-the-table” Netflix account-sharing scheme unites digital Christian worshippers, gig economy hustlers at home, and the country’s North American diaspora in Canada and the United States.

Tens of thousands of Zimbabwean immigrants living in New York City or Toronto have access to both global credit cards and Netflix accounts. In contrast, in their country of origin, a global debit or credit card is hard to obtain due to years of domestic banking restricted from global finance connectivity by U.S. Department of Treasury sanctions.

If you don’t have a global debit or credit card, you can’t get a Netflix account. And if you don’t have access to reliable Wi-Fi, you can’t successfully stream Netflix offerings.

The Alliance for Affordable Internet has documented that Zimbabwe is home to some of Africa’s most expensive broadband internet access. Few residents can afford to buy 1.4GB of data, which costs a whopping $15 a month, a figure that’s double AAI’s global benchmark of 2% of average monthly income.

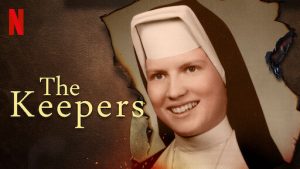

Yet the religion content — including shows like “The Keepers” — on Netflix is extremely popular in Zimbabwe, where both internet access and global bank cards are hard to come by.

Yet the religion content — including shows like “The Keepers” — on Netflix is extremely popular in Zimbabwe, where both internet access and global bank cards are hard to come by.

Entrepreneurs have devised a workaround: A Mastercard holder in New York or Toronto lends his Netflix account password to a jobless family member or friend 8,000 miles away in Zimbabwe. That Zimbabwean targets very poorly paid white-collar government workers who have access to their employer’s free Wi-Fi at work in numerous skyscrapers that dot the capital of Zimbabwe. The highly educated civil servant (clerk, social worker, tea-brewer) — usually a devout Pentecostal Christian — is sold the account login for a certain number of hours per day because he doesn’t have a Mastercard but has access to his employer’s lavish office Wi-Fi.

In largely evangelical, devout Zimbabwe, premium Christian shows, films, crusades, sermons and podcasts in English via Netflix are highly coveted.

Admire Moyo, 27, a “Netflix hustler” in Harare, explained: “I have four MasterCard debit cards of my brother’s in Canada and which I ‘rent’ here in Harare to civil servants who poach their employer’s Wi-Fi.”

There’s a reason why Netflix is the go-to channel for Christians hungry for content. “In the past, people in Zimbabwe used YouTube to find free films. But YouTube no longer has free series,” Moyo explained.

In another version of the scheme, a typical North America-based Zimbabwe diaspora resident buys a Netflix package that allows five people and five devices to log in at the same time. That package is cheaper in the U.S., UK and Canada than in Zimbabwe. Then the password is given to a family member in Zimbabwe who sells it for $15 to “renters” in Zimbabwe who are eager to access premium Christian shows via their employer’s Wi-Fi.

“I opened Netflix with my brother’s MasterCard, but I have no internet at home, so what is the use? When I sell the log-in details to renters, I can control usage by simply trying to log in too. If the system refuses, I know my customer is connected, watching premium Christian shows using his employer’s Wi-Fi,” Moyo said.

These off-the-books deals are very beneficial to “hustlers” who sell the logins to devout Christians keen to exploit their employer’s Wi-Fi and pass time in very poorly paid civil service jobs that dim their professionalism — and to the Zimbabwean diaspora abroad in the U.S., Canada or Australia.

“If I give the passwords control to my siblings overseas in Zimbabwe, and they ‘rent’ to office workers seeking Christian films, they earn money and don’t bother to ask me to wire food, clothes or money from North America.”

“I have several Netflix accounts but hardly have time to watch the shows,” said Simangaliso Dhoro, 40, a Zimbabwe HVAC serviceman in Toronto who was born in Harare. “If I give the passwords control to my siblings overseas in Zimbabwe, and they ‘rent’ to office workers seeking Christian films, they earn money and don’t bother to ask me to wire food, clothes or money from North America.”

These schemes are hilarious but understandable, according to Desmond Bunza, a Pentecostal pastor in Harare who complains that scores of members of his congregation, who are civil servants, now dodge midweek services because they will be busily hooked to Netflix American Christian shows via their employers’ free Wi-Fi.

“After COVID-19 receded in 2021 and workers returned to office, I heard these Netflix ‘account-hustlers’ made more money than churches tithes,” he said.

Deogracias Kalima contributed reporting to this story.

Related articles: