Stella Immanuel — the Cameroonian-American doctor at the heart of this country’s most recent culture war skirmish over the novel coronavirus and the effectiveness of hydroxychloroquine as a treatment — believes certain medical conditions are the result of “evil deposits” from demonic spirits often referred to as spirit spouses.

To put it bluntly, Immanuel believes many of the problems that afflict the human reproductive system, conditions that range from endometriosis to miscarriage to erectile dysfunction, are caused by people having sex with demonic spirits.

Trevor Noah of The Daily Show” making jokes about Stella Immanuel’s beliefs.

Coupled with many of her other eccentric and conspiratorial beliefs, Immanuel’s theology of demon sex has been widely used by Western media to discredit and ridicule her. Trevor Noah even went so far as to label her “Dr. Demon Sperm.”

Which is a fine enough opinion for a professional comedian, if a bit pedestrian. But Immanuel’s beliefs did not emerge in a vacuum, and her regular posts on social media suggest that she fervently believes these things to be true. She is, after all, a pastor as well as a doctor.

What might we learn if we put down the weapons of the culture war and instead really listened to the deeply held, if startlingly unfamiliar, beliefs of a fellow Christian? In the end, we might still fervently disagree with Immanuel’s theology, but let us seek first to understand.

In the beginning

While it can seem far-fetched at first blush, there is actually a kind of compelling internal logic to Immanuel’s theology of spirit spouses (also sometimes called “demonology”). She begins where most studies of demons begin, with the mysterious stories in the book of Genesis. In the days before the great flood, Genesis 6 speaks briefly of “Nephilim,” powerful beings who seem to be the offspring of human women and the “sons of God.” These sons of God, Immanuel argues, are actually the fallen angels of Revelation 12 (who, it should be noted, never appear in Genesis; we can thank both John of Patmos and John Milton for their addition to the story).

These fallen angels know that God already has promised their destruction under the heel of woman’s offspring, so it becomes their mission in life to attempt to corrupt women and their offspring. The bodies of these Nephilim are then destroyed in the great flood, leaving their souls to wander the earth as demonic spirits.

Stella Immanuel in a highly controversial video taken down from social media because of unproven claims about cures for coronavirus.

What is less familiar to most, and therefore less compelling, is Immanuel’s coupling of demonic forces with the notion of spirit spouses. Spirit spouses are common in a number of indigenous religious traditions, and although the traditions vary widely, they are usually conceived of as positive or neutral forces who aid those to whom they are connected. Typically, an encounter with a spirit spouse involves a sexual dream or vision.

African Pentecostalism

Part of the genius of indigenous African Pentecostalism, the Christian tradition to which Immanuel loosely belongs, is that it did not try to challenge the traditional African cosmologies it encountered. Unlike much of Western Christianity, which derided other gods and spiritual forces as pagan, impotent and worthy of destruction, African Pentecostalism found ways to incorporate spirit spouses and other spiritual powers into a new theological framework.

Spirit spouses thus lose their neutral or beneficial moral cast and become grafted onto Christian conceptions of demons. They no longer bring luck but misfortune, often related to the real family of their victim. And the accompanying sexual dreams become sources of sexual pollution.

Thankfully, Jesus’ victory over the powers of sin and evil includes triumphing over spirit spouses, and the church is given the task of exorcising these demonic spirits, something often referred to as “deliverance ministry.”

Parallels in Christian history

Here it should be noted that, while Immanuel’s theology might seem uncomfortable and unfamiliar to many Western Christians, it actually has numerous parallels throughout Christian history. Immanuel’s account of the origin of these demonic spirits, for example, sounds an awful lot like 1 Enoch, a Jewish apocalyptic book, and the Clementine Homilies, a 4th century Christian romance. Medieval theology also featured demonic spirits that sound very similar to spirit spouses. Incubi and succubi were demons who seduced human beings with the goal of corrupting their souls.

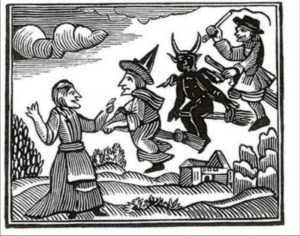

A 1689 woodcut of witches flying, from Mathers’ “Wonders of the Invisible World.” (Public Domain)

As late as the early 1600s, no less important a figure than King James VI was still publicly debating whether or not demons could reproduce with humans (he and Immanuel disagree on the method, but both believe it is possible). Even in our contemporary scientific reality, many candidates for baptism are asked to “renounce the evil powers of this world.”

What about consent?

The problem, ultimately, with Immanuel’s conception of demons is not the demons themselves, but rather the moral universe in which they function.

The language of “marriage” to a spirit spouse implies a consensual relationship. One might not fully understand what being married to a demon means, but at least it is something one does on purpose. Only, Immanuel believes spirit marriages can be passed on through generations or communities, or that they can be initiated by sitting under the teaching of a pastor who is “sexually unclean.”

In all three scenarios, the individual has done nothing wrong. In fact, in the case of the compromised pastor, she or he has actually attempted something good — seeking out spiritual guidance. But in all three situations a door has been opened for demonic activity. In this moral universe, the demons have a legal right to the individual, even if the individual did not consent to the relationship.

It might seem innocuous, or even appropriate. After all, bad things happen all the time to people who do not consent to those bad things. But if even miniscule or well-intentioned actions give demonic spirits legal claims to people’s lives (Immanuel cites wearing makeup and jewelry, watching Harry Potter, or listening to Beyoncé as examples), soon people will be neurotic balls of spiritual anxiety, worried that any action at all will grant a demon power over them.

Should we be talking about this?

It should be no surprise, then, that most theologians who deign to talk about demons worry about the topic. C.S. Lewis warned about “an excessive or unhealthy interest in them,” and Thomas Aquinas’ teacher Albert the Great once said of the subject: “It is taught by the demons, it teaches about the demons, and it leads to the demons.”

Indeed, excessive concern for demons actually has the potential to move beyond our simple fascination and into the realm of active harm.

“The problem with most demonologies is that they are, at root, about blaming the victim for things that often have no discernable cause.”

Immanuel has become famous for attributing gynecological and reproductive problems to demonic activity, but people who suffer from the debilitating pain and potential infertility of endometriosis did not invite their suffering. They did not cause their own disease by cavorting with demons. People who are experiencing the searing loss of a pregnancy already cannot help but wonder if they did something to cause it; the last thing they need in this traumatic situation is someone callously confirming their deepest fears.

The problem with most demonologies is that they are, at root, about blaming the victim for things that often have no discernable cause. It is reckless theology and worse pastoral care.

Who has the power?

Given all this, it can be tempting to dismiss not just Immanuel but demonology in general. Certainly, a majority of American Christians do just that. But the problem with demonology is not the demons themselves but rather what we ascribe to them and how we interpret them.

In the early 1960s, William Stringfellow faced a similar problem. An accomplished lawyer and lay theologian, he had been invited to give two lectures at Harvard: one to the divinity school and one to the business school. He gave roughly the same address to both groups, a speech that linked his experiences with impersonal systems of institutionalized prejudice with the demonic powers and principalities that Paul wrote of.

In the early 1960s, William Stringfellow faced a similar problem. An accomplished lawyer and lay theologian, he had been invited to give two lectures at Harvard: one to the divinity school and one to the business school. He gave roughly the same address to both groups, a speech that linked his experiences with impersonal systems of institutionalized prejudice with the demonic powers and principalities that Paul wrote of.

At the divinity school, Stringfellow was chided for his antiquated, mythological belief system. What use, they marveled, is a theology that cannot describe the real world! But at the business school, they hung on every word. They knew from their own experiences how the faceless and inhuman system of capitalism was used to diminish human lives — their own included — for the sake of maximizing profit margins. They might not have used words like “demonic” or “powers” to describe their experiences, but they knew Stringfellow was describing their exact experience of the real world.

This is the truth that both Stringfellow and Immanuel teach us: There are oppressive spiritual forces — yes, demons — active in this world. The problem is not the demons themselves, but how we interpret them.

Illness, even debilitating illness, is a fact of life in this present age and does not need to be attributed to sinful activity with sexual demons (Jesus himself even explained that illness is not a punishment for sin). But systems of racism so pervasive they no longer need individual racists to perpetrate racist outcomes? Those are demonic, and the church has a responsibility to exorcise them.

Aaron Coyle-Carr

Aaron Coyle-Carr is a graduate of Candler School of Theology at Emory University. He’s currently a stay-at-home dad, Bible study teacher and researcher based in Dallas. He is married to Leanna Coyle-Carr, who also is a Baptist pastor.