Nigeria, Africa’s most populous country, has in recent weeks attracted global attention for a series of mind-boggling, alarming crimes: At least 76 farmers were beheaded by the terrorist group Boko Haram in a farm in Zabarmari, Borno State, in late November; more than 330 students of Government Secondary School, Kankara, in Katsina State went missing after a band of bandits, later revealed to be Boko Haram members, invaded their school dormitory Dec. 11 (the students regained freedom a week after), and about 22 persons were reported missing after another set of gunmen swooped on homes in Tegina and Ogu communities in Niger State, west central part of the country Dec. 13.

Reduced to a footnote in between these incidents was the reported arrest of the suspected killers of Haruna Kuye, a Christian and district head of Gidan Zaki in Atyap, Southern Kaduna, and his son, Destiny Kuye, in early December. Father and son were killed in mid-November. The news of the arrest of the suspects, even as the investigation of their motive is yet to be made public, draws attention, once again, to the long, checkered history of violence and bloodletting in Southern Kaduna.

The story behind this violence has its roots in religion and its hope in newly named peace commissions. But to understand the religious conflict, one must understand the people and their history.

Historical roots of violence

Located in the middle belt region of Nigeria and spread across some of the 23 local government areas of Kaduna State, Southern Kaduna comprises a mainly Christian majority and a minority Muslim population. Among its local governments are Zangon Kataf, Jema’a, Kaura and Lere. Despite their shared humanity, inter-ethnic and religious crises have more often than not been associated with the people.

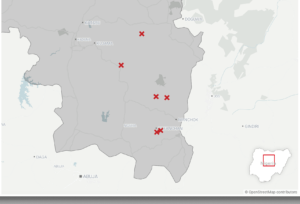

Locations of violent acts in Southern Kaduna, Nigeria, in July 2020.

Such is the level of violence in Southern Kaduna over the decades that few Nigerians, if compelled to, could recall the number of conflicts that have broken out in the area, let alone state the casualty figures. But respective governments in the state and federal authorities did set up investigative panels on major crises witnessed there.

The introductory part of the “Report of Zangon Kataf Market Riots Judicial Commission of Inquiry June 1992” is instructive, as it provides insight to the level of destruction of lives and property in the area and state generally.

It states in part: “Prior to the 6th of February 1992, the small and quiet town of Zango in the heart of Zangon Kataf Local Government of Kaduna State, was known by only a few people in this country Nigeria. However, the sad events of the 6th day of February 1992 coupled with the subsequent riots of the 15th and 16th May 1992, not only brought this town into the limelight but virtually made it a household name in Nigeria and beyond.

“Thousands of lives had been lost and property worth hundreds of millions of naira destroyed.”

This commission was deliberating on its report when on May 16, 1992, news filtered in that riots had broken out again in Zangon Kataf. At the end, “thousands of lives had been lost and property worth hundreds of millions of naira destroyed not only in Zango town but within Kaduna and its environs, Zaria and Ikara.”

Since then, many more people have lost their lives in subsequent conflicts in Kaduna State. An Aug. 24, 2020, report by Amnesty International states: “On 6 August at least 22 people were reported killed when gunmen suspected to be herders attacked four communities in Zangon Kataf Local Government Area of the state. More than 100 people were killed in July during 11 coordinated attacks in Chikun, Kaura and Zangon-Kataf Local Government Areas of the state. At least 16 people were killed in Kukum-Daji on 19 July 2020, in an attack that lasted for five minutes, when attackers shot sporadically at villagers.”

Who is the victim?

In virtually all the conflicts, both the Muslim and Christian sides claim to be the victims. This is because claims of assault or violence by a particular group against the other are often repudiated and instead blamed on the accuser. While the Christian group, for instance, and its sympathizers tend to use words such as “ethnic cleansing,” “genocide” or “jihad’ to describe the clashes that broke out in the communities over the years, the Muslims of Fulani stock typically refute such accusations and insist they, instead, have borne the brunt of the carnage.

John Praise

In August, the Pentecostal Bishops Forum of the 19 Northern States in Nigeria called on the Nigerian authorities to boost the security apparatus in Southern Kaduna and bring an end to killings, which it believes weighs heavily against Christians. Speaking through its chairman, John Praise, at a news conference in Abuja, the country’s capital, the group called for the prosecution of the perpetrators of violence and their sponsors.

“The situation had assumed a dangerous dimension of ethnic cleansing, going by the methodology and clinical decimation of the population of the indigenous people with mindless ruthlessness,” Praise said. “The audacity of the recent attacks and the inaction of the relevant security formations to bring the perpetrators to justice suggest a wicked collaboration, double standard and sabotage in certain quarters.”

Claims of genocide

Reiterating this viewpoint, Luka Binniyat, a 55-year-old native of Zamandabo village, in Atyap Chiefdom and spokesperson of Southern Kaduna Peoples Union, insists that what has been happening in Southern Kaduna is genocide.

Luka Binniyat

“The allegation of ethnic war against Christians in Kaduna State is real,” he reported. “Today, 102 farming communities of Southern Kaduna have been (annexed and the people) chased out and most are occupied by armed herdsmen. We have evidence of genocide with the mass graves dotted all over our landscape.”

Binniyat accused Muslims, comprised of Hausa and Fulani people, of seeking to achieve what their forebears could not.

“During the Othman Dan Fodio Jihad of the 1800s, not a square inch of Southern Kaduna was captured by the invading jihadists and slave raiders. Sadly, after the defeat of the caliphate and all other Hausa powers, the British who conquered Southern Kaduna handed the land and its people to the Muslim feudal authority under British indirect rule,” he reported. As a result, “our people suffered massive suppression and persecution under the feudal system.”

Binniyat added that the relationship between the Christian population in Southern Kaduna — whose portion of the population he estimates to be 90% — had been “that of mutual mistrust, punctuated by sparks of violence at uneven intervals dating back to the 1942 and 1965 Zangon Kataf and Zonkwa riots respectively.”

“The violence is targeted at rural Christian farming communities.”

However, “in the past, all the violence had its known causes. And they were largely urban based, … the violence was usually put out by state might and hardly lasted more than two days,” he said. “But from 2014, the pattern changed. The violence is targeted at rural Christian farming communities where homes and churches are burned, pastors and their families killed or kidnapped and the village displaced and taken over by armed herdsmen. It is now invasion and occupation with the invaders well known and identified, and nothing is done.”

The ethnic crisis, Binniyat said, is exacerbated by the policies of Nasir el-Rufai, governor of the state, whom he described as pro-Muslim.

Nasir El-Rufai

As an example, he noted that previously political appointments were shared 50-50 between Christians and Muslims. If the governor of the state was a Muslim, his deputy would be a Christian and vice versa. But Governor Nasir el-Rufai “has made a mockery of that arrangement. He picked a Muslim to be the deputy governor. Of the 14 commissioners in the state, only four are Christians. The 12 top jobs in the state are all (held by) Muslims. The two federal ministers representing Kaduna State are Muslims. Of the over 30,000 civil servants sacked by him, the majority are Christians.”

An alternative perspective

Adamu Mohammed Kagarko, chairman of the Southern Kaduna Muslim Ummah Development Association, denied that Muslims have been the ones instigating violence in the land.

Adamu Mohammed Kagarko

“The claims by some Christians that the Muslims who are in the minority in the area are often the perpetrators of this violence are totally false. In simple laws of life, how can we agree with the assertion that the minority can be an aggressor against the majority?” he wondered.

“The majority Christians in the area have access to the media, hence they are always dishing out false narratives to the world. Unfortunately for the Muslims, the media hardly come to balance such narratives. We are, however, glad some of the media like yours (Baptist News Global) are now practicing investigative journalism to balance reports.”

Kagarko availed this reporter of a book and another report, which he said enumerates the loss suffered by Muslims in some of the crisis in Southern Kaduna. The report, titled “Southern Kaduna Killings, Beyond the Propaganda,” contains images of dead people, slain animals and razed settlements from January to August this year. It was compiled by the Muslim Youth Foundation of Southern Kaduna. It states that “Southern Kaduna violent conflict has been age-long, complex and is growing in intensity and complication due to refusal to accept, accommodate and manage diversity in the area due to leadership failure. The main fault lines range from religion to ethnicity with politically motivated and growing criminal element.”

This report asserts that “the dominant group who control local political and customary power are the so-called indigenous Christians, (who) claimed that the area is their ancestral land. The so-called settlers are the Muslim minority who resist to be second-class citizens. The ensuing conflict is driven by attempts of the dominant group to uproot the minority group and the attendant resistance thereto that gave rise to attacks and counter attacks.”

And yet the losses still mount

Funeral after an attack on the village of Gora Gan on July 20. (Photo: Twitter/Steven Kefason)

While the accounts differ, what is indisputable about the decades-long Southern Kaduna conflict is that both Christians and Muslims have, over the years, suffered incalculable loss in human and material terms. The recurring crisis, some observers say, is due in part to the machinations of elites stoking divisions within the domains for their own selfish gain, as well as the failure of successive state and federal governments to decisively deal with culprits to serve as a deterrence to mischief makers.

Salim Musa Umar, chairman of the Farmers and Herders Initiative for Peace and Development Africa, while noting that claims of ethnic cleansing in southern Kaduna are exaggerated, said the cost to both sides has been enormous.

“There is no way you can exonerate the two parties of complicity in the security challenges in southern Kaduna,” Umar said. ‘There were attacks and reprisals in many communities. What is exacerbating the crisis is the religious colorations often cited in all the attacks and reprisal attacks.

“What is exacerbating the crisis is the religious colorations often cited in all the attacks and reprisal attacks.”

“The reason is not farfetched: almost all herdsmen are Muslims while the farmers are Christians. So, there is a thin line between the two sides, which often gives credence to religious perspective of the crisis. So, the fundamental issues are often neglected, and focus is shifted to the more appealing words of ethnic and religious cleansing, which in reality are exaggerated.”

And yet there is hope

While numerous peace committees over the years have failed to achieve their goals in southern Kaduna, some concerned persons in the area are not giving up hope yet. Their optimism for a society where people, irrespective of their religious or ethnic identities, co-exist peacefully with others, led to setting up a new committee called the Atyap Chiefdom Peace and Security Partnership Committee. It was inaugurated on Friday, Oct. 2, in the council chamber of Agwatyap Palace.

John Bala Gora

The peace committee is headed by John Bala Gora. Speaking on how the committee came about, Gora said it was a product of a summit by Atyap stakeholders in August that recommended “for a standing peace committee to nip in the bud any threat to peace in the chiefdom.” He said that following its formation, members consulted with one another, carved the group into subcommittees with set goals and also reached out to other organizations for assistance. The committee members include Christians, Hausa, Fulani and others, and they “appear genuinely committed to ensuring lasting peace in the Chiefdom.”

Gora added that the state government has been supportive of the peace agenda.

“We are working together with the State Peace Commission for funds/materials to resettle and rehabilitate those whose homes were destroyed,” he said. “The economic and entrepreneurial subcommittee has identified trades and skills to train our young men and women for self-employment. It is our strong belief that if we pursue these with vigor and diligence, most of our young men and women would be meaningfully engaged.”

Meanwhile, the Kaduna State Peace Commission was established by el-Rufai’s administration in 2017.

In an interview with Channels TV early last year, ahead of the governorship election in the state, El-Rufai, who was seeking re-election, addressed critics who accused him of religious bias in his choice of a deputy governor.

“Even if I choose the pope as my running mate, some 67% of Christians have made up their mind that they will never vote for me,” he asserted. “This is what the polls show. For me, that’s not the issue. The issue is this: Kaduna State is divided; it needs to be united. The way to begin to unite it is to take religion and ethnicity off the table. Since 1992, every deputy governor of Kaduna State has been a Christian. What has it done for the state? Has it united the state? Has it assuaged the feelings of the Christian minority that they are part of the government?”

Beyond the talks, the overriding concern should be how to stamp out violence and attain lasting peace in Southern Kaduna and the state and Nigeria in general.

A lesson from the past

Kagarko recalls that there once was a time when indigenes of Southern Kaduna lived in peace and harmony and hopes for a return to those days.

“It is never a difficult thing for Muslims and Christians in Southern Kaduna to live in peace. For some of us we have lived peacefully with one another in the past,” he said. “We remember those old good days when Muslims and Christians enjoyed and shared memorable moments during festivities, visited and stayed in one another’s towns and villages …, went to and assisted one another on the farms without any discrimination. All these good old times are no more. The reason for that was our selfish elites and some politicians from both sides.”

Salim Musa Umar

For Umar — who revealed he’s a victim of Nigeria’s ethno-religious crisis that is not limited to Southern Kaduna, having personally suffered huge losses in nearby Plateau State where he resides — any effort at sustainable peace should be championed by the people.

“As a peace practitioner, I don’t subscribe to the popular notion that federal and state governments should be the ones to resolve conflicts in our communities. The communities themselves should lead the crusade for ensuring peace in their domain. Government should only provide the enabling environment for peace to strive in all communities. Over-reliance on government for all solutions is the reason crisis is commercialized by crisis agents. Communities should as a matter of principle and priority own their peace, nurture it and guard against any breach to peaceful co-existence,” he advised.

Anthony Akaeze is a Houston-based journalist who began his career in his home of Nigeria. He specializes in reporting on faith from an African perspective.

This article was made possible by gifts to the Mark Wingfield Fund for Interpretive Journalism.