This week, I’m returning to the Shomburg Center for Research in Black Culture in Harlem to read letters from James Baldwin to literary, political and Civil Rights leaders. Then on Sunday, at the historic Church of the Incarnation on Madison Avenue, I’ll be preaching about Baldwin’s thoughts on what we render to Caesar and to God, then talking about Baldwin.

I can’t stop talking, thinking and learning about James Baldwin, because I can’t stop talking, thinking and learning about how we can and must do better on the big questions of race, justice, faith, love and courage where we can still hear Baldwin’s prophetic voice calling for change.

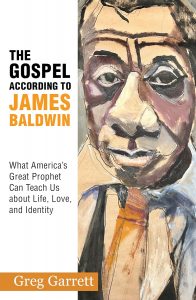

Greg Garrett

I spent six years of my life writing The Gospel According to James Baldwin, although there are many differences between Baldwin and myself. I’m a straight white middle-class Christian man with too many college degrees and some ancestral familiarity with livestock and tractors. Baldwin was a gay Black artist born and raised in Harlem who fled the church and the country and who never went to college.

Yes, we looked and loved and believed differently. But Baldwin remains one of my most heeded voices on the universal human issues he wrote, spoke and preached about, one of the most exalted in my pantheon of human teachers alongside Dr. King, Maya Angelou and John Lewis.

As I write this lead-in to the book excerpt that follows, The Gospel According to James Baldwin is the top seller in the Christian Liberation Theology category on Amazon. That fact comes not because I wrote such a good book — although I do believe it is a book people will find of use — but because so many love and treasure the liberating wisdom of Baldwin, and because there are so many new to Baldwin who will find him a light speaking into the darkness and helping to guide them home.

I hope you will enjoy this short selection from the introduction to The Gospel According to James Baldwin, published by Orbis Books.

******

I came to Switzerland — three hours on a high-speed train from Paris, three hours on a local train to the village of Leuk at the base of the Alps, an hour sitting in the hot sun — Switzerland was also immersed in a general European heatwave — for the bus into the Alps, and what turned into the longest 45 minutes of my life as we climbed and switchbacked and slowed to a crawl to negotiate tight curves and avoid oncoming traffic — and please God, Greg, do not look out that window — because I believe in my heart and in my bones that James Baldwin matters. That he spoke and is still speaking to us. And that anything that might help me better understand his life and his work — even this trip up the side of a mountain, the worst amusement park ride of all time — was something to be explored, reflected on and valued.

I also believed Mr. Faulkner was right about each artist’s individual postage stamp, that although James Baldwin had his own very particular set of human experiences, his writing and his life offer universal truths. Different as we are, we are not so different, in the end.

I also believed Mr. Faulkner was right about each artist’s individual postage stamp, that although James Baldwin had his own very particular set of human experiences, his writing and his life offer universal truths. Different as we are, we are not so different, in the end.

Like Baldwin, I have loved and lost, have been laid low by depression and heartbreak, have contemplated stepping off the planet. Like Baldwin, in my life I have been constricted and even damaged by the exercise of religion in my vicinity. Like Baldwin, I have been scarred by the unwanted attentions of a powerful white man who was used to getting anything he wanted. Like Baldwin, I have felt isolated and misunderstood, pushed to the margins because I see the world thoughtfully and try to exercise my art faithfully. And like Baldwin, I have attempted to figure out who I am, have tried on various identities and beliefs, have sought what makes a life worthwhile and a community worth living and dying for.

Every book I have ever written — it’s more than a few now — has grown out of this desire to understand. It’s not a thing I do lightly, taking on a new project even with as compelling a subject as James Baldwin. Writing is often painful, with daily failures that can crush your spirit. Like many writers, I’m committing myself to years of thought and effort and months away from my family, and I have discovered that at heart, like Baldwin, many days I really would just prefer to spend time with the people I love and enjoy some good talk and food and drink. Like Baldwin, I want to throw myself head first, soul deep, into loving the person who makes my heart sing, and yet here I am sweating my way into the Swiss Alps while my bride is fixing our girls breakfast in Austin, Texas.

“James Baldwin speaks directly to all the big things that keep us up at night.”

But also, like Baldwin, I believe some people do have a special calling, whether because they can see the world a little more clearly, or because they can write about it a little more cleanly, or both. Baldwin had those gifts. He thought of himself as someone called to witness, someone who could help all of us understand ourselves and our world a little better because of what he saw and what he wrote. Baldwin was, like his stepfather, a preacher in his youth, and he knew the Scriptures as well as the figures in them. He saw himself as a prophetic figure like Jeremiah, a person given a special commission to tell the truth, no matter how hard or how painful.

Baldwin matters and will always matter because he took that call seriously, because his writing and his life confronted everything we struggle to figure out, everything that still has us hiding in our gated communities. Maya Angelou spoke at his funeral about one of their visits: “We discussed courage, human rights, God and Justice. We talked about Black folks and love, about white folks and fear.”

James Baldwin speaks directly to all the big things that keep us up at night, to racism, to American identity, to human sexuality, to the various kinds of violence human beings do to each other, to faith and meaning, and to the prophetic role of the artist.

Indeed, James Baldwin has been weighing down my backpack, my syllabi and my heart because this Black gay expatriate writer is and always will be an exquisitely thoughtful guide to What Matters, whether in the Age of Kennedy, the Age of Obama, the Age of Trump, or the Age of Whatever Comes Next.

I followed his footsteps into a remote village in the Alps not because I expected to meet him there — actually, I meet him daily — but because I believed this quest might help me meet myself. That’s what great artists do — out of their own experience, through their command of image and language, they hold up a mirror that helps us to see and know ourselves, helps us to learn, to love, to hope.

Greg Garrett teaches creative writing, film, literature and theology classes at Baylor University. He is the author of two dozen books of fiction, nonfiction, memoir and translation, including the critically acclaimed novels Free Bird, Cycling, Shame and The Prodigal. His latest novel is Bastille Day. He is one of America’s leading voices on religion and culture. Two of his recent nonfiction books are In Conversation: Rowan Williams and Greg Garrett and A Long, Long Way: Hollywood’s Unfinished Journey from Racism to Reconciliation. He is a seminary-trained lay preacher in the Episcopal Church. He lives in Austin with his wife, Jeanie, and their two daughters.

Related articles:

Stranger in the Village: James Baldwin and inclusion | Opinion by Greg Garrett

A message to white Christian America: Remember the church at Sardis | Opinion by Wendell Griffen