While deeply committed to his Christian faith, Martin Luther King Jr. was influenced by Buddhist, Hindu and Jewish ideas in formulating and leading the Civil Rights movement, said Jonathan Eig, author of the new biography, King: A Life.

Input from interfaith sources also contributed to the much-maligned anti-war theology King unveiled at the height of the Vietnam conflict, Eig said during a recent podcast episode of “Interfaith America with Eboo Patel.”

Patel, president of Interfaith America, said he was struck by Eig’s description of King’s simultaneous devotion to Baptist Christianity and to principles gleaned from other faith traditions.

“I’m curious: What do you make of this deep believing, Black Baptist for whom Christianity is the root and center and the anchor and the north star, whose faith is totally changed by Mahatma Gandhi, whose politics on the Vietnam War is totally changed by a Buddhist, who marches arm-in-arm with a Jew in Selma, and whose closest companion in the Civil Rights movement is a white atheist agnostic communist, Stanley Levinson? What do you make of that?”

Jonathan Eig

King’s embrace of interfaith dialogue and learning was an outcome of his experience as a Black pastor in the South and of his understanding of Scripture, said Eig, who also has written biographies of Muhammad Ali, Jackie Robinson and Lou Gehrig.

“I make of it that he actually believes what he’s reading in the Bible, and he doesn’t think that only his version of the Bible, or his religion, is the right one,” Eig said. “The most fundamental thing he takes from the Bible is the idea of love. God loves all of his children. God doesn’t love only his Christian children. God doesn’t love only his Black or white children. God created everybody in God’s image. I think he’s applying it in the broadest, greatest potential way he could.”

King relied heavily on Jewish leaders to infuse the movement with that concept of love, said Eig, who is Jewish. A key adviser was Rabbi Abraham Joshua Heschel, the theologian and activist King once praised for his “prophetic insights.”

“They certainly deserved a lot of credit, and King had many great, close friends and advisers in the Jewish community,” Eig said. “In reading King’s own words, in reading the interviews with him, he absolutely valued and treasured his Jewish allies.”

Also important to King were the teachings of Gandhi, the Indian leader whose philosophy of nonviolent civil disobedience helped end British colonial rule in India. But as King: A Life points out, “it’s not just a methodology that King is learning in nonviolence. It is a new definition of agape, of Christian love,” Patel said.

Gandhi’s effect on King was deep, Eig said. “We know Gandhi is a massive influence on his worldview, on his approach to faith.”

But King also was inspired by Gandhi’s statement that nonviolent disobedience could be effective in the American Civil Rights movement, he added. “He sees Gandhi as a template for much of what he’s doing. I think those words must have resonated with King because he’s trying to prove that Gandhi might have been right.”

An early instance of that influence came in King’s 1955 speech announcing the Montgomery bus boycott, Eig said. In it, the Baptist leader appealed to biblical and constitutional values in a way that resonated with Black churchgoers, the media and other clergy.

An early instance of that influence came in King’s 1955 speech announcing the Montgomery bus boycott, Eig said. In it, the Baptist leader appealed to biblical and constitutional values in a way that resonated with Black churchgoers, the media and other clergy.

“He’s saying: ‘We’re not here to attack America. We’re here to join America. We’re here to unite all these different beliefs, and we want to make American democracy better.’”

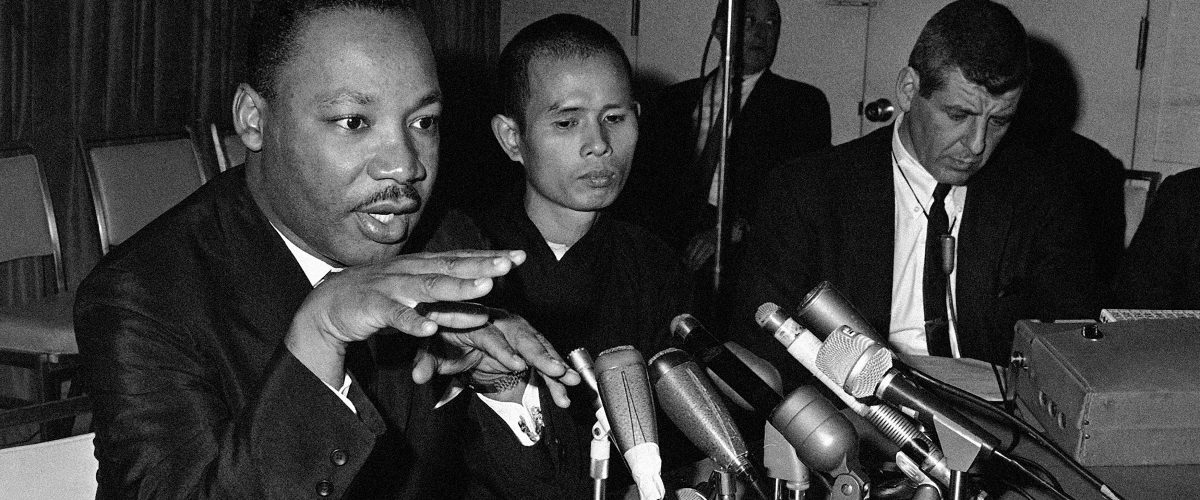

But in 1967, the guidance of a high-profile Buddhist teacher led King to deliver a sermon condemning U.S. involvement in Vietnam, a move that drew condemnation from the White House, the media and much of society.

“The only person King ever nominates for the Nobel Peace Prize is a Buddhist monk, Thích Nhat Hanh, … who does more than any other single person to change King’s mind about his volume on the Vietnam war,” Patel said.

King’s embrace of interfaith dialogue is often and sometimes purposely overlooked because it is complex and challenging, Eig said. “We’re not as comfortable talking about his radical Christianity in particular. We’ve softened him to the point that he wouldn’t recognize himself in this vision that we’ve created — ‘I Have a Dream.’ So much of what he did was driven by his faith, and when he had doubts, he turned to that every time.”

An example came when King faced pressure to abandon the protest movement and return to his pulpit full time after his home in Montgomery was bombed in 1956. But he received direct, divine intervention to do otherwise, Eig said.

“He sat down and heard the voice of God telling him: ‘Go on. This is what you’re called to do.’ I found in some archives another example where he said, yet again, a second time, he heard the voice of God speak to him.”

The problem is the nation seems to respect its Black heroes only after they have become irrelevant, feeble or have passed on, the author said. Muhammad Ali, the boxer and Muslim reviled for his faith and for refusing to fight in Vietnam, was invited to light the Olympic torch in 1996.

“Ali was only loved when he could no longer speak, when he wasn’t challenging American ideas anymore, when he was safe. The same goes for King. When we turned him into a national holiday and a monument in Washington and quote, ‘I have a dream,’ we forget he was attacking police brutality in that same speech at the March on Washington, that he was attacking the economic injustice that had particularly taken a heavy toll on Black Americans.”

But King would warn against becoming disillusioned by the injustices in society, Eig said. “He spoke so often about the fact that we could never lose hope, that the key for the future was to stay awake and to be receptive, to change and to not become cynical as things change, but to be open-minded and willing to adapt, knowing that you still had that faith.”

Related articles:

What you haven’t been taught about Martin Luther King

More than a dream: The undiluted legacy of Martin Luther King Jr. | Analysis by Joel Bowman Sr.

Remembering the real Martin Luther King: Forgive us, Lord | Opinion by J. Alfred Smith