While most American churches are debating whether and how they can safely resume in-person worship anytime this year, a Southern California parachurch ministry has come under intense scrutiny for holding massive revival services at Huntington Beach.

Organizers and supporters of Saturate OC have tried to characterize their beach revival as a new iteration of the Jesus People movement of the 1960s and ’70s, but many members of the surrounding Orange County community see the events as endangering public health.

While some churches are moving ahead with limited capacity services that do not include singing and require parishioners to wear masks, others, following the lead of Atlanta megachurch Pastor Andy Stanley, are planning not to meet again in person until 2021. Still others are experimenting with outdoor worship with physical distancing in place. This debate has become so fraught that when Christian ethicist David Gushee wrote a call to consider reopening some congregations with precautions in place, he prompted a flurry of online criticism and public response and calls for BNG to remove his article.

This photo posted to Facebook by Saturate OC shows a crowd gathered at Huntington Beach with only two people wearing face masks.

In Southern California, the evangelical revival movement Saturate OC has disregarded the rising number of COVID-19 cases and refused to adjust its movement to the evolving pandemic, claiming the work of God cannot be shut down.

The husband and wife team of Parker and Jessi Green serve as directors of the movement. The couple claims to have had a vision back in 2016 of a massive revival on Huntington Beach in Orange County. In this vision, they saw thousands of people being baptized. There would be so many people waiting to receiving baptism, that after being baptized a person would have to turn around and baptize the person waiting behind them.

Despite the rising number of infections in the state of California, the Greens decided to push forward with realizing their vision. Beginning on July 3 and continuing on July 10, 17 and 24, Saturate OC held mass gatherings at Lifeguard Tower 20 on Huntington Beach. The organizers encouraged participants to bring and wear masks and to practice social distancing as they felt led while on the beach. However, photos of the rallies posted on social media showed neither masks nor social distancing in use.

The Christian Post reported that some individuals are seeing this “beach revival” as the “beginning of a new Jesus Movement.” Sean Feucht, who led worship music at the event, said Saturate OC serves as “a return back to a gritty, raw gospel, Jesus people movement foundation.” While the event envisioned thousands, it drew only hundreds of passionate individuals who gathered for prayer and worship.

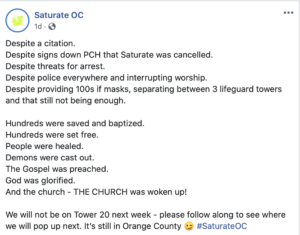

Many residents of Orange County, however, did not receive the revivalist movement with enthusiasm. An online petition sought to cancel the gatherings. Saturate OC failed to receive the proper permits for their gatherings and violated numerous state and county public health orders, resulting in a city citation, according to one local news source.

The Facebook page for Saturate OC embraced local resistance as a form of persecution. A video posted from the July 24 gathering read: “Last day on the beach / Citation and all! / Officially illegal worship and preaching even with masks!” Saturate OC plans to continue into August, but they are advertising that they will no longer meet at Lifeguard Tower 20 following the gathering on July 24.

The Facebook page for Saturate OC embraced local resistance as a form of persecution. A video posted from the July 24 gathering read: “Last day on the beach / Citation and all! / Officially illegal worship and preaching even with masks!” Saturate OC plans to continue into August, but they are advertising that they will no longer meet at Lifeguard Tower 20 following the gathering on July 24.

It is easy to criticize Saturate OC for how they conveniently selected which public health guidelines they would follow and which they would disregard. The organization’s vague website suggests some individuals may have stood to gain financially from registration fees, donations and merchandise sales. Director Jessi Green’s Facebook page characterizes her as an “Entrepreneur” first and a “Preacher of the Gospel | Evangelist” second in the page’s “about” section.

The claims that this movement draws inspiration from the “Jesus People” of the 1960s and ’70s, however, raises questions regarding the organizer’s knowledge of this brief movement.

Scholars struggle to categorize the “Jesus People” from that era. A charismatic movement, the Jesus People, sometimes referred to as “Jesus Freaks” emerged out of the counter cultural movement of the 1960s. Once former hippies who had sought spirituality through peyote, LSD and other drugs, the Jesus People claimed to have found spiritual bliss through an experience with the Holy Spirit.

The group had little organization, and some pockets of the movement looked quite different from others. Some segments of the Jesus People practiced communal living, sharing everything from food and shelter to clothing and spending money. Their time was highly organized and structured. Sociologist David Gordon described the typical day of one community as filled with “worship meeting, chores, Bible and evangelism classes, group counseling, street witnessing, individual Bible study, and perhaps work in a specialized area such as the group’s newspaper, band, drama troupe, or one of the group’s service businesses.”

Other groups of Jesus People might be less communal in their organization, and individuals would have jobs and identities outside of the movement. What gave these disparate groups a common identity as Jesus People, Gordon suggested, was a synthesis of the moral and religious order individuals learned in childhood and the counter-cultural youth movement. Some members of the Jesus People movement leaned more toward the counter-cultural movement, whereas others leaned more toward the conventionality of their childhood upbringing.

Racial tension, societal unrest and profound partisanship do indeed characterize both our current climate and the climate that birthed the Jesus People. The reported youthfulness of Saturate OC and its focus on discipleship also parallels the Jesus People, but the similarity dissolves there.

Comparing Saturate OC to the Jesus People reveals a group of Christians who long to be counter-cultural but hold on to a Christian theology that very much supports the cultural status quo. While some in the group may consider defying public safety measures as an act of countering a culture of fear, in reality, it is simply dangerous and unsafe.

Marketing themselves as a modern-day Jesus People only further showcases where Saturate OC diverges from this earlier movement. From their savvy branding to encouraging individuals to bring a credit card to ”purchase merch,” Saturate OC seems to sell the experience of a movement that pushed against an individualized consumerism.

Marketing themselves as a modern-day Jesus People only further showcases where Saturate OC diverges from this earlier movement. From their savvy branding to encouraging individuals to bring a credit card to ”purchase merch,” Saturate OC seems to sell the experience of a movement that pushed against an individualized consumerism.

Hitching their wagon to the Jesus People “brand” may also prove to be a short-lived strategy. While the Jesus People grew quickly in the late ’60s and early ’70s, they also declined just as quickly. Perhaps the most lasting influence of the Jesus People can be heard in contemporary Christian worship music.

While some youth may have had genuine, life-changing experiences through these gatherings on Huntington Beach, it is important to remember the Jesus People developed a synthesis between their moral upbringing and the youth movements of the era.

If Saturate OC were interested in forming such a synthesis today, they would be looking to the young gun control activists who rose up after the shooting at Stoneman Douglass High School in Parkland, Fla. They would be looking to synthesize their movement with the groundswell of youth climate activists and young Black Lives Matters activists.

Yes, the Jesus People Movement was largely apolitical, but today’s youth are not.

Andrew Gardner holds a Ph.D. in American religious history and is the author of Reimagining Zion: A History of the Alliance of Baptists (2015).