On June 1, 1921, the Greenwood district of Tulsa, home to more than 10,000 Black residents, was intentionally destroyed by a white mob. An estimated 300 Black residents died; close to 1,000 were seriously injured.

Every home in the 30-block section of town was razed to the ground. A thriving business section was erased from the map. The newly constructed Mount Zion Baptist Church, the pride of the community, disappeared along with a dozen other places of worship.

Alan Bean

Twenty-five years later, Nancy Feldman, a young social worker and teacher, moved to Tulsa. She never had heard of what is now called the Tulsa Race Massacre until she visited with Robert Fairchild, a recreation specialist who survived the incident. Horrified by Fairchild’s account, Feldman broached the subject with her freshman college students.

“No one in this all-white classroom of both veterans, who were older, and standard 18-year-old freshmen, had ever heard of it,” Feldman says, “and some stoutly denied it and questioned my facts.” When Feldman invited Fairchild to share his childhood memories with the class, the denial verged on open revolt. Students had asked their parents and grandparents about the massacre and were assured it never happened. Feldman was called to the dean’s office and instructed to drop the matter.

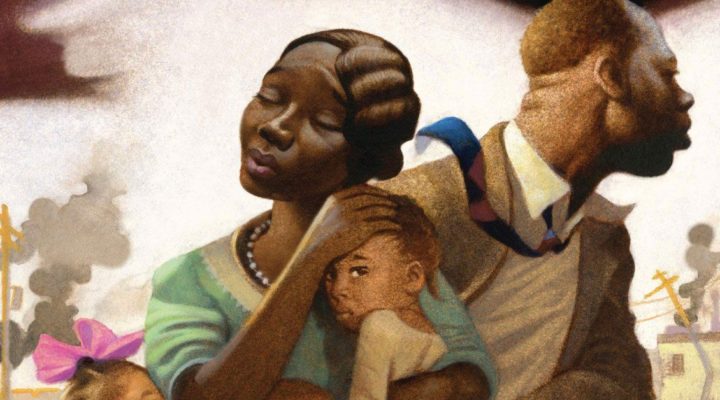

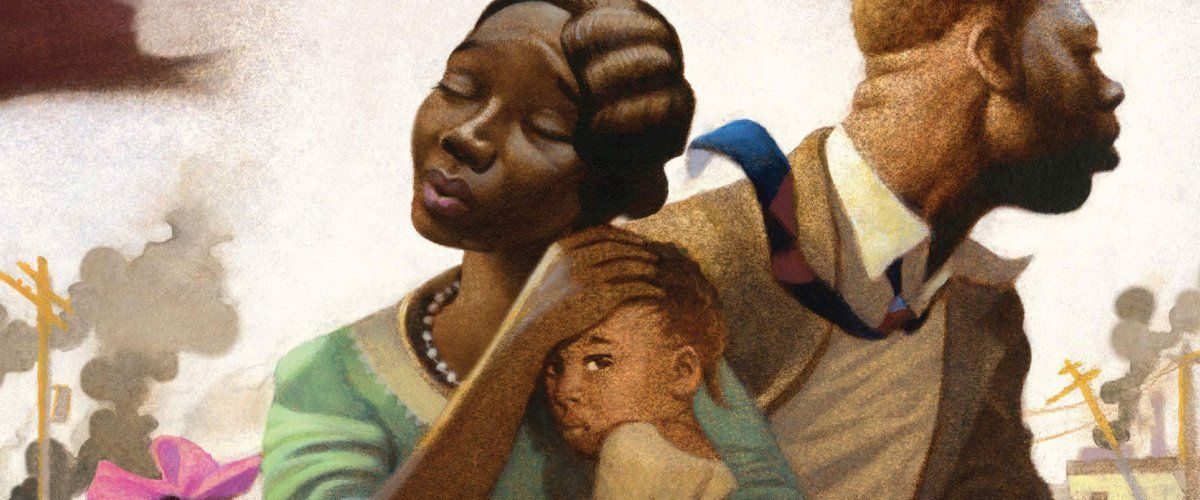

Which is why Carole Boston Weatherford, writing in 2021, calls her children’s book Unspeakable: The Tulsa Race Massacre. It’s a quick read (this YouTube reading is just 11 minutes long) because the target audience is children from 8 to 12.

Floyd Cooper, the illustrator, grew up in Tulsa’s Black community. “Everything I knew about this tragedy came from Grandpa,” he says in a note at the end of the book. “Not a single teacher at school ever spoke of it.”

How do you speak the unspeakable to an 8-year-old child? How does an artist portray realities this horrific for a young audience?

How do you speak the unspeakable to an 8-year-old child? How does an artist portray realities this horrific for a young audience?

Weatherford and Cooper approach their subject with gentle restraint. They don’t address every ugly detail. There are no descriptions of bullets ripping through defenseless children, or of airplanes owned by the Sinclair Oil Co. dropping incendiary bombs on homes, businesses and churches. Nor is the story told from the perspective of a child screaming in horror as her parents die in agony and her world dissolves in flame.

Weatherford and Cooper focus on Greenwood, a community known as “Black Wall Street.” They want young readers to see how Black residents bravely defied Jim Crow laws designed to keep them weak and impoverished.

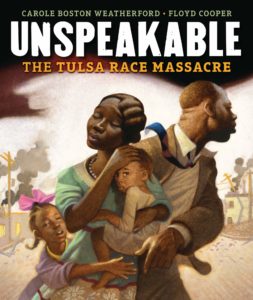

“Once upon a time on Black Wall Street,” Weatherford tells her readers, “there were dozens of restaurants and grocery stores. There were furriers, a pool hall, a bus system, and an auto shop — nearly 200 businesses in all. There were also libraries, a hospital, a post office and a separate school system, where some say Black children got a better education than whites.”

Next, Weatherford and Cooper treat us to a whirlwind tour of Greenwood in her glory days. We see a proud mother and daughter standing in front of the newly constructed Mount Zion Baptist Church. The elegant home of A.C. Jackson, “the most able Black surgeon in the nation,” stands in the background.

“Only after Greenwood is presented as a cohesive community distinguished by its beauty, nobility and community pride is the demonic specter of white supremacy allowed to deface the portrait.”

Then we are introduced to Miss Mabel’s Little Rose Beauty Salon. “On Thursdays when maids who worked for white families got coiffed on their day off and strutted in style up and down Greenwood Avenue.”

Through word and picture, we learn about the Stradford Hotel (“the largest Black-owned hotel in the nation”) and the 800-seat Dreamland Theater.

At this point we are 16 pages into a 30-page book, and the massacre hasn’t even been mentioned. Only after Greenwood is presented as a cohesive community distinguished by its beauty, nobility and community pride is the demonic specter of white supremacy allowed to deface the portrait. The spirit of this community, they suggest, fell victim to a carefully orchestrated lynching.

The title, “Unspeakable,” refers in part to the horror of Greenwood’s destruction. But Weatherford is also addressing the conspiracy of silence that has long obscured the truth.

In 2001, 80 years after the Greenwood massacre, the Oklahoma Legislature commissioned a study into this unspeakable chapter of state history. The “most repugnant fact” the 200-page report encountered “is that it was virtually forgotten.”

The facts were silenced to serve “the dominant interests of the state.” For too long, the massacre was regarded as a “‘public relations nightmare’ that was ‘best to be forgotten, something to be swept well beneath history’s carpet’ for a community which attempted to attract new businesses and settlers.”

The facts were silenced to serve “the dominant interests of the state.” For too long, the massacre was regarded as a “‘public relations nightmare’ that was ‘best to be forgotten, something to be swept well beneath history’s carpet’ for a community which attempted to attract new businesses and settlers.”

That silence has been broken. As the centennial of the Greenwood horror approached, a torrent of podcasts and documentaries appeared, and the tragedy has been featured in a variety of made-for-television dramas. BO’s Watchmen and Lovecraft County (both multi-episode series employing elements of “magical realism”) have used the Greenwood massacre as a dramatic backdrop. Aimed at adults, these entertainments highlight the most distressing details of the story.

At the other end of the entertainment spectrum, the History Channel has produced “Tulsa Burning: The 1921 Race Massacre,” and CNN has given us “Dreamland: The Burning of Black Wall Street.” And if you think the rape of Greenwood is a historical anomaly, there is Raoul Peck’s mind-numbing “Exterminate all the Brutes,” a five-part HBO series revealing the genocidal aspect of Western imperialism.

So, the unspeakable is finding a voice. Given the carefully manicured telling of American history in the classrooms of America, it is unsurprising that this sudden roar of unsolicited information is creating shockwaves throughout conservative America.

“The bill also bans any form of communication that makes students experience ‘discomfort, guilt, anguish or any other form of psychological distress on account of his or her race or sex.’”

In 2001, the Oklahoma Legislature stipulated that the Tulsa race riot (as it was then called) should be incorporated into public school curriculum. Twenty years later, they have reversed themselves by passing HB 1775, which stipulates that public and charter school students must not learn that, by virtue of their race, they bear responsibility for actions committed in the past by other members of the same race.” The bill also bans any form of communication that makes students experience “discomfort, guilt, anguish or any other form of psychological distress on account of his or her race or sex.”

Is it now illegal to read Unspeakable: The Tulsa Race Massacre in the classrooms of Oklahoma?

No healthy student, regardless of race, can read this story without feeling “discomfort” or “anguish.” No white student can read Unspeakable without experiencing guilt and shame. If white children don’t conclude that they “bear responsibility for actions committed in the past” they have missed the point.

Will the elementary teachers of Oklahoma have the courage to assign Unspeakable to their students, or to read the text aloud while children peruse illustrations of professionally attired Black families fleeing from white folks bent on genocide?

I hope so; but I doubt it. This material is incendiary because it is true. Like HB 1775, Unspeakable bristles with implications for the America of 2021. Who are we? How did we get this way?

Weatherford and Cooper have given us some clues. The Oklahoma Legislature is intent on shutting them up. Who will blink first? I’ll tell you one thing; It won’t be the author and illustrator of Unspeakable. They’re just getting started.

Alan Bean is executive director of Friends of Justice, an alliance of community members that advocates for criminal justice reform. He lives in Arlington, Texas.

Related articles:

It’s not just the SBC banning Critical Race Theory; now state legislatures are joining the fight

Juneteenth should remind us of all the things we don’t know | Opinion by Mark Wingfield

I’m weary of hearing “I’m sorry” from white people | James Ellis III

Dear white Christians, are you done praying yet? | Opinion by Natasha Nedrick