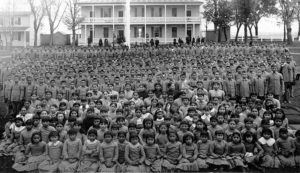

Secretary of the Interior Deb Haaland announced the United States will launch an initiative to search for possible burial sites at the former grounds of the federally created Native American boarding schools that forcibly removed thousands of children from their culture and communities.

The announcement came after the horrifying discovery of the remains of 215 First Nations children in a mass grave in British Columbia at one of Canada’s largest former residential schools for indigenous people. A month after this initial finding, an additional 751 unmarked graves linked to another boarding school were uncovered in Saskatchewan.

The new U.S. program called the Federal Indian Boarding School Initiative will locate and identify the sites of the American schools, search for possible buried remains of children and determine the identities and tribal affiliations of the children.

Deb Halland

Haaland, the first Native American cabinet secretary, recognized the inter-generational impact created by the schools and committed “to shed light on the unspoken traumas of the past, no matter how hard it will be.”

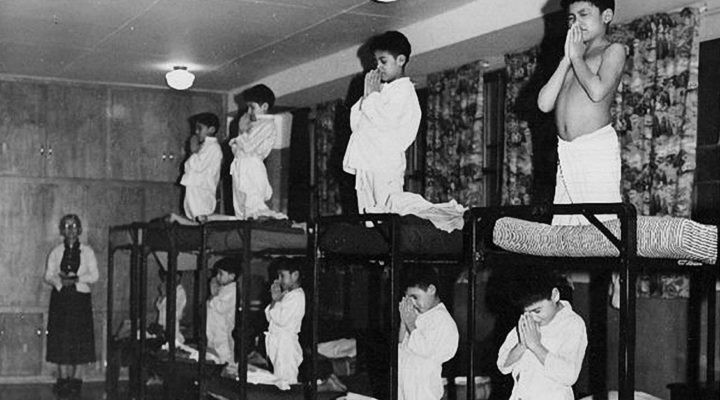

Native American boarding schools were created out of the Civilization Fund Act of 1819, which aimed to “civilize” native populations. The goal of these schools was to erase and replace identity. It was an attempted cultural genocide. Children were given new European names, forced to cut their hair and forbidden from speaking native languages or practicing native religions.

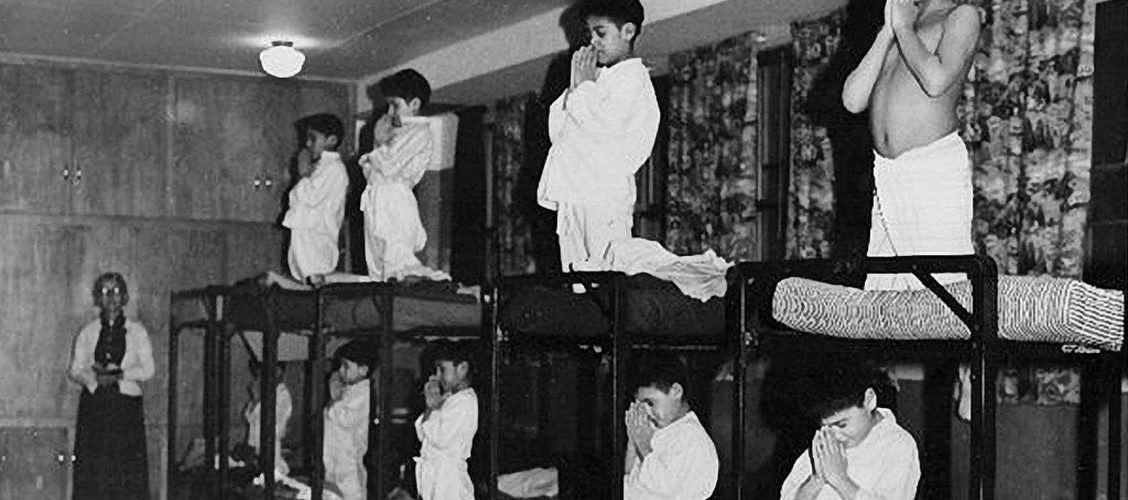

Captain Richard Henry Pratt, who established the first Native American boarding school and designed it after a prison system, infamously said the school’s purpose was to “kill the Indian, save the man.”

The schools were not always residential. But when given the option to return home, the students did not fully abandon their cultures in order to assimilate into Euro-American culture. As a result, children were abducted and forcibly enrolled in boarding schools — often taken miles away from their communities to ensure they didn’t try to return home. These schools became a vehicle for one of the original forms of family separation in the U.S.

Many children were physically, emotionally and sexually abused when they did not comply with the school’s idea of civility, and some did not survive the “education.”

Lt. Richard Henry Pratt, founder and superintendent of Carlisle Indian School, in military uniform, 1879. (Wikipedia)

The age of Native American boarding schools represents not only a hideously dark period in U.S. history, but also a dark period in Christian history. While funded by the federal government, the schools largely were run by Christian missionaries and clergy. The children were forced to give up their native religions to learn Christian theology because Christianity was seen as an imperative aspect of what it meant to be civilized.

The Board of Indian Commissioners allocated certain schools and native tribes to different Christian denominations, including Methodist, Presbyterian, Episcopalian, Catholic and Baptist. Of the 73 Indian agencies allotted to Christian denominations, five agencies in Utah, Idaho and the Indian Territory were assigned to Baptists, accounting for 40,800 Native Americans.

The same kind of attempt to forcibly assimilate Native Americans into a new culture was reflected in the attitude of mandatory Christian conversion, as Euro-American exceptionalism and Christian nationalism were conflated as one in the same.

Pupils at Carlisle Indian Industrial School, Pennsylvania, c. 1900 (Photo: Wikipedia, common domain)

Pratt documented his role in establishing the first boarding school in his autobiography Battlefield and Classroom. He told the 1883 Baptist World Convention, “In Indian civilization I am a Baptist because I believe in immersing the Indians in our civilization and when we get them under, holding them there until they are thoroughly soaked.”

It would be easy to assume Baptists’ horrifying involvement in these boarding schools is little more than a shameful ghost of the distant past. But the last Native American boarding school of this kind was in operation until the 1970s, and native communities continue to suffer from the inter-generational trauma of an attempted erasure of identity, community and culture.

This trauma and others faced by Native Americans have been linked to high rates of suicide, substance abuse and addiction. “Many who survived the ordeal returned home changed in unimaginable ways, and their experiences still resonate across the generations,” Secretary Haaland noted.

Christine Diindiisi McCleave

These boarding schools are more than merely a thing of the past for native communities. “Our children were taken, and they’re lost, and we don’t know where they went, and we don’t know what happened to them. We don’t know their final resting place,” said Christine Diindiisi McCleave, chief executive of the National Native American Boarding School Healing Coalition.

There is a shroud of uncertainty and a lack of education around the details of what happened at these schools. The government has committed to work toward unveiling the truth of this past wrongdoing. Will the church have enough bravery and humility to make the same commitment?

In a news release responding to Haaland’s announcement, President Jonathan Nez of Navajo Nation said, “This troubling history deserves more attention to raise awareness and to educate others about the atrocities that our people experienced, so that they can better understand our society today and work together to heal and move forward.”

There needs to be more awareness, research and truth-telling on harms committed against Native Americans in the name of the Christian God. And while it is unclear exactly how many schools and how many children were affected by this Christian and government creation, there is evidence Baptists were involved.

Heather Dawn Thompson stands on a Rapid City, S.D., hillside overlooking the site of the long shuttered Rapid City Indian Boarding School. Researchers determined that some children who died at the school were buried on the hill. (Stewart Huntington/Indian Country Today via AP)

Acknowledging this sin is the only way forward. The National Native American Boarding School Healing Coalition recommends that churches conduct and distribute research on denominational involvement in the schools, consult with affected native communities on appropriate next steps and offer statements of acknowledgment and apology.

Other denominations have taken the first step to issue a formal statement of apology for their institutions’ role in Christian colonialism and harm toward Native Americans. No Baptist denomination has issued such a statement.

A written report of the Federal Indian Boarding School Initiative’s findings will be given to Haaland in April 2022. As the initiative begins and the report offers more transparency, how will Baptists respond to newly unearthed hard truths? Will Baptists help dig into our own sordid history, or will we rebury a reality we’d rather not confront?

Laura Ellis currently serves as a Clemons Fellow with BNG. She recently graduated from Boston University School of Theology with a master of divinity degree. She is originally from Abilene, Texas.

Related articles:

Confessions of a good white guy | Opinion by Alan Bean

Critical Race Theory, voter suppression and historical negation: The irony of it all | Opinon by Bill Leonard

Six ideas for decolonizing Thanksgiving | Opinion by Luhui Whitebear and Susan M. Shaw