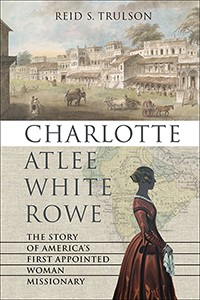

Recognition is long overdue for Charlotte Atlee White Rowe, the first American woman appointed by any denomination or mission agency as an international missionary.

Charlotte White’s controversial 1815 appointment by the Baptist Board of Foreign Missions forced her to contend with gender bias because she was not an ordained man. Henry Holcombe, a member of the board and pastor of Philadelphia’s First Baptist Church, believed in women’s “inferiority in some respects” to men and led the effort to revoke her appointment, believing that it constituted a “usurpation of authority over the man.” When others resisted sending her by pleading insufficient resources, Charlotte contributed her modest estate for her own support.

The controversy continued until the board resolved that appointing single women missionaries was “not expedient in the future, as far as they can now judge.” That blocked other women from fulfilling their call to missions.

The controversy continued until the board resolved that appointing single women missionaries was “not expedient in the future, as far as they can now judge.” That blocked other women from fulfilling their call to missions.

One who was blocked was Eliza Yoer, who moved to Philadelphia to begin preparing for mission service but returned to Charleston when she was not appointed. Another, a Miss Dunning from New York, likewise was not appointed even though she was interviewed, found suitable for service in India, and her brother had pledged to fund her work.

In April 1816, after 129 days at sea, Charlotte White and fellow missionary George Hough arrived in Calcutta (now Kolkata) en route to Burma. During the months it took to find a ship sailing to Rangoon (now Yangon), Charlotte met and married Joshua Rowe, a widowed British Baptist missionary with three young sons. She remained in India and worked with the British Baptist Missionary Society that regarded Charlotte and other missionary wives as unofficial mission assistants. Andrew Fuller, the society’s first secretary, held that since women did not preach, “they ought not to be called missionaries.”

Charlotte White Rowe and her husband served at Digah, some 360 miles northwest of Calcutta. There she overcame prejudice against educating local children. Indeed, an East India Company director maintained that England had lost the American colonies due in part to the folly of having allowed schools and colleges to be established in America and warned Parliament against repeating the mistake in India. But Charlotte persistently advocated for education, wrote a Hindi spelling book and grammar as teaching aids, recruited teachers and started Hindi-language schools for both girls and boys.

Charlotte persistently advocated for education, wrote a Hindi spelling book and grammar as teaching aids, recruited teachers and started Hindi-language schools for both girls and boys.

She also withstood new scandal when her confidential correspondence was repurposed in Philadelphia for anti-missionary propaganda.

Joshua Rowe died in 1823, leaving Charlotte the single parent of six children. For the next three years she worked at Digah without assistance from missionary colleagues. She alone managed the mission, supervised 10 schools, taught, organized construction and repair of schools and mission buildings, oversaw the Hindi-language church at Digah, and guided the ministries of indigenous itinerant evangelists who called her “their pastoress.” As her missiology matured, she adapted her work to the local culture, critiqued the role of money in missions, and challenged the system of language acquisition for new missionaries.

Charlotte left Digah in November 1826 to seek financial support from the Baptist Mission Society under whose auspices she had given a decade of self-funded missionary service. In London she found that official appointment by British Baptists would cause as much scandal in England as it had earlier in America. Women attending the society’s jubilee meeting 15 years later were told, “Ladies, it is not yours to be supreme, it is ours. It is yours to obey.”

Despite her significance as the first appointed woman missionary, Charlotte was consistently omitted from early mission accounts.

Despite her significance as the first appointed woman missionary, Charlotte was consistently omitted from early mission accounts. This led to her absence in later women’s studies and mission histories. Knowledge of her life and ministry now has emerged from research into previously unexplored source materials in India, England and the United States.

Charlotte did not seek fame, likening herself to a seemingly insignificant ant working with others to build a large, pyramid-like anthill on an Indian plain. Like the ant, she did “not shrink from doing little — doing many littles.” Yet she exerted a powerful influence by daring to open the door for women to receive full and equal missionary appointment with men.

Charlotte Atlee White Rowe ended her work in India on Nov. 1, 1826 — 175 years ago. Her appropriate recognition is long overdue.

Reid Trulson

Reid S. Trulson is the retired executive director/CEO of International Ministries. He previously served as the American Baptist representative to Europe in Austria and the Czech Republic, area director for Europe and the Middle East, Scripture Union regional secretary in Ghana, and as an American Baptist pastor in California and Wisconsin. He is the author of Charlotte Atlee White Rowe: The Story of America’s First Appointed Woman Missionary.

Related articles:

Black Baptist women in ministry and the principality of patriarchy | Opinion by Aidsand Wright-Riggins

Book traces the complex story of women’s influence within Southern Baptist Convention

Baptists celebrate Judsons in Burma