Everybody deserves to have that one person in life who sees your true potential and is determined to bring it to fruition. I was fortunate to have such an encourager, who was my boss for five years, my friend for almost four decades, and one of the best people I’ve ever known. And now he’s gone.

Jack E. Brymer Sr. died Oct. 28 at St. Vincent’s Birmingham Hospital (Ala.) at the age of 84 after a recent stroke. He was one of the brightest lights among Baptist journalists in the last half century — perhaps the most consequential semi-century for Baptists since they emerged on this continent.

Jack Brymer

Jack first made his mark in Baptist journalism at a time when newsprint was still king and pastor-publishers rivaled denominational executives for power and influence. There were better-known editors during the period, and maybe more influential ones. But few journalists had an impact as broad or as varied — on his generation and the one that followed — or paid a higher price for it.

Jack’s career spanned four-plus decades — from the countercultural ’60s to the post-Christian ’00s. It was an era of cataclysm for Southern Baptists, who morphed from being the faith-by-default of the Jim Crow South, through their own not-so-civil war when fundamentalists forced a painful split with progressives, and finally becoming outspoken culture warriors and political allies with the evangelical right and GOP.

This file photo from The Alabama Baptist shows five native Alabamians who in the 1980s served as editors of state Baptist papers: James Langley, Jack Brymer, Jack Harwell, Hudson Baggett, and Bobby S. Terry.

Jack labored quietly for 19 years as managing editor of the stodgy The Alabama Baptist, then and now one of the largest Baptist publications. But rather than waiting another decade for editor Hudson Baggett to retire, Jack accepted the editorship of the Florida Baptist Witness in 1984.

The early Florida years

From Day 1 he made it known he was no clone of Baggett, Alabama’s peace-at-all-costs editor. With the fundamentalist controversy now fully aflame in the SBC, Jack made it clear his commitment to core Baptist principles meant he was more likely to make waves than make nice.

“Local church autonomy mandates that Baptists receive a full accounting of what is taking place, even if it is unpleasant,” Brymer told the Florida convention.

But Jack’s vision for the Witness included not just telling the whole truth but doing it with quality and style. In one of his first meetings with his directors, Brymer waved a copy of Missions USA, the old Home Mission Board’s award-winning glossy magazine, and promised his version of the Witness would match up with the best Baptists had to offer.

It was a tall order that probably drew a few chuckles from his board members. The SBC’s mission boards always attracted the best feature writers and photojournalists, equipped them with generous travel and print budgets, and regularly stole all the honors offered for religious publications.

It was a tall order that probably drew a few chuckles from his board members. The SBC’s mission boards always attracted the best feature writers and photojournalists, equipped them with generous travel and print budgets, and regularly stole all the honors offered for religious publications.

Jack’s readers and editor peers soon took notice, including Marv Knox, then editor of Kentucky’s Western Recorder and later the Baptist Standard of Texas, but earlier one of the writers Jack admired at Missions USA.

“When Jack became editor of the Florida Baptist Witness, he changed the way I thought about Baptist newspapers,” Marv told me soon after Jack’s death. “Who knew a Baptist newspaper could be beautiful?”

Tough-but-fair reporting

Brymer inherited the mantle of tough-but-fair reporting and courageous editorial writing, Marv recalled, “but also felt newspapers should do more.”

For one thing, Brymer believed the Witness could become more effective by becoming visually attractive. To prove he was serious, Jack first hired graphic designer Lindsay Bergstrom of Texas, even before he interviewed news writers.

“Who would have imagined design could heighten the impact of articles?” Marv asked rhetorically. “Jack did. And with Lindsay, he taught many of us important lessons about communication.”

“Jack hired a pair of talented journalists and gave them free rein to expand the focus and function of the newspaper,” Marv continued. “Under Jack’s guidance, Greg Warner wrote articles designed to prompt broad discussion about systemic and cultural issues.”

“For example, (in 1986) the Witness provided extensive coverage about the church’s response to AIDS when a multitude of pastors wouldn’t even say the word in public.”

At the Witness, we took on other topics usually taboo for Baptist publications — homosexuality, child sex abuse and ministerial burnout among them. And when presumptuous pundits and preachers claimed to know what Baptists believed about inerrancy and other hot-button issues, the Witness instead hired public-opinion researchers to ask them — and then wrote about it.

It was the chance to write those articles — “deep dives” that could make a difference — that caught my interest when Jack approached me about a job in 1985.

At the time, I was living in Fort Worth, Texas, and working at the SBC Radio and Television Commission, my first journalism job after seminary and grad school. I was anxious for a new career challenge and was in fact weighing two other job offers — one in Atlanta and another in Washington — both of which were on my “dream job” list.

Jack and I never had met but, with a nudge from Baptist Press editor Dan Martin, he had started reading my bylines and decided I should be his associate editor.

Jack was not only right, his timing was fortuitous; I found out later I was about to be laid off in the next round of RTVC budget cuts. One quick trip to Jacksonville, and Cheryl, our newborn and I were loading the U-Haul for Florida, our home state.

Coming from an oppressive work setting, I wanted a job with both the freedom and expectation of excellence. Jack’s leadership was refreshing — a hands-off boss with a light editor’s touch who not only expected excellence, he enabled and rewarded it. Pretty quickly the Witness felt like home.

A true colleague

I gladly called Jack my boss and offered him deference when it seemed important. But he preferred I be a colleague, and he treated me as a peer. That was true not only in the office but beyond, even in settings where deference was de rigueur. Jack detested pretense and hypocrisy, especially when it was attached like gilding to ministers and the ministry.

Each February, the Association of State Baptist Papers held their annual meeting at a place and time concurrent with the state convention executives. It was always at a posh, far-away resort — in Hawaii, Canada, New England — because the execs did the picking. Six months on the job, with the audacity of innocence, I asked to go.

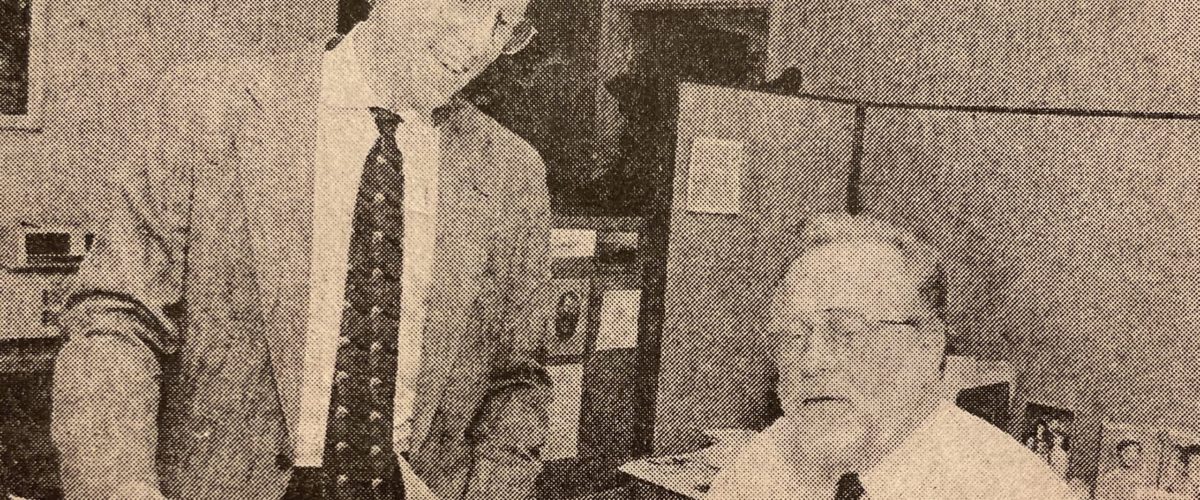

The Florida Times-Union published this photo of Greg Warner and Jack Brymer in 1990.

No one told me — not even Jack — the trip was for the editors only, not their associates. Later Jack explained the cold stares from some editors. And, as it turned out, he too had earlier breached the editors’ code by attending, but only after many years as the Alabama associate. We had a good laugh about it. And I kept going to the meetings.

In that and much more important ways, Jack ensured I was included and empowered at every step. I didn’t know why he put such great effort into my success. I was pretty sure I didn’t deserve it, but it made me feel special.

As it turned out, the truth was … neither! It didn’t matter whether I deserved it; it was Jack’s nature and conviction to help me thrive. And I wasn’t even special. There were quite a few young Baptist journalists whom Jack mentored or otherwise aided and encouraged.

A mentor to others

Among them were at least two who also became Baptist newspaper editors: Jennifer Rash and Marv Knox. Each offered firsthand testimony of Jack’s wider influence.

“Jack invested in many young communicators through the years. … I was once one of those young communicators,” said Jennifer Rash, an Alabamian like Brymer, but they met while each was living and working in Florida.

“Jack Brymer mentored and guided at least one generation of Baptist journalists,” said Marv, who became the best known and most respected journalist of my generation. Brymer’s mentees included “many of us who never worked directly on a newspaper with him.”

Marv worked for four Baptist newspapers and several SBC agencies and now serves with the Fellowship Southwest.

SCAV 1139 VM24,613

Jim Sulzby, Andrew Tampling, Hudson Baggett, Louise Barbour, and Jack Brymer

“Very early in my career, the Home Mission Board sent me to Birmingham to cover a bus boycott opposing systemic racism,” Marv recalled. “A local missionary organized a network of church buses to help domestics and other laborers get to and from work.

“I told their story in what I felt was an uplifting human-interest story,” he continued. “Hudson Baggett, editor of The Alabama Baptist, not only rejected my article but also called my bosses to ream me out through them. For the first time in my young life, someone powerful questioned my character and lambasted me for doing a ‘bad job.’”

Someone else from The Alabama Baptist also called. But that call — from managing editor Jack Brymer — was to affirm Marv.

“Jack couldn’t override his boss’ edict,” Marv reported, “but he let me know I wrote a good story and could hold my head up for telling the truth.”

Jennifer said she first became familiar with Jack through his work with the Witness while she was working for an SBC-affiliated publishing house in Hollywood, Fla., that served Christians in the Caribbean.

“Jack encouraged me when I needed it, challenged me when I needed it, and always cheered for me,” she explained. “He even scolded me once when (in my late 20s) I felt inadequate to be leading a workshop on communications to pastors and leaders twice my age.

“Jack encouraged me when I needed it, challenged me when I needed it, and always cheered for me.”

“He could tell I was a bit insecure,” said Jennifer, normally a fount of effervescent energy. “So he pulled me aside, reminded me I had been selected to participate for a reason, and told me to quit worrying about it, to just get in there and share everything I knew with the group. He snapped me out of the stupor. And with a simple, ‘Yes, sir,’ I bounced back into the room and never looked back.”

While Jennifer was far from alone in getting a boost from Jack, their connection has a poignant circle-of-life quality.

“Little did I know then that I would eventually sit in his managing editor chair at The Alabama Baptist just a few years later,” she explained. But she didn’t stop there either.

Empowerment of women in leadership

First hired as news writer in 1996, she rose through the ranks of The Alabama Baptist to the No. 2 spot Jack held for 19 years. Then in 2015 she was named editor-elect. With the retirement of longtime editor Bob Terry in 2019, Jennifer became president and editor-in-chief of The Alabama Baptist — the first female editor of a major U.S. Baptist newspaper.

Jack can’t take credit for Jennifer’s historic achievement, but he would lead the chorus of those celebrating it, before adding his own blunt interpretation: “That took too damn long!”

Jack supported the full inclusion and empowerment of women — in Baptist journalism and in all roles of Christian leadership — long before it was politically safe to do so. If I needed proof, I didn’t have to look far.

In the office next to mine at the Witness was Lindsay Bergstrom, the graphic designer Jack hired to revamp the look of the Witness. Although she never had lived outside Texas, Lindsay moved her husband and three young children to Jacksonville in June 1985.

“It was a really tough summer,” she recalled. “It was the first time I had been so far from friends and family in Texas. … Then there were the relentless deadlines that state paper work required. I cried many days that summer as I tried to get a footing in this new world. Had it not been for Jack, I might have given up.

“Jack was kind, soft-spoken, funny, sometimes a bit irreverent, but one of the giants of the faith for me, and I loved him deeply,” Lindsay said.

“The greatest gift Jack gave me was confidence.”

“The greatest gift Jack gave me was confidence,” she continued. “For the almost 11 years I worked for him, Jack loved and supported me … even in those times I made mistakes. With each mistake came a teaching moment.

“He was my mentor, but more importantly he was my friend,” she concluded.

When I joined Jack and Lindsay at the Witness a little later in 1985, I discovered Jack’s high expectations were not going to be my biggest challenge. The SBC battle over inerrancy was dividing Florida Baptists too, and some conservative pastors intended to make the Witness one of the battlegrounds.

Facing the critics

While Jack and I were in agreement about reporting contentious news without fear or favor, every Florida pastor, and almost every reader, seemed convinced they could do our jobs better. We knew that because they told us, or rather they told Jack. I usually didn’t find out until later, because Jack took most of those bullets for me.

At least once a week, some influential pastor would call or write complaining about something I wrote, or was about to write, and demand that Jack retract or spike it. But he seldom mentioned those demands to me.

When I did find out and asked him about it, he made it clear: “That’s my job,” he said. In effect: ”You do your job; I’ll do mine.”

And that was that.

“For Jack, each critic was just a friend who didn’t know it yet.”

To my amazement, no matter what level of vitriol readers hurled at Jack, he treated each with respect. For Jack, each critic was just a friend who didn’t know it yet.

Often he would ask an irate reader to put his or her criticism into a letter to the editor. Jack believed even his critics deserved to be heard.

“As Baptists, we must protect the right of every Baptist to have his point of view heard with impunity,” Jack said in one of his early reports to the Florida Baptist Convention.

There is a cliché about writing letters to the editor: “Don’t pick a fight with someone who buys ink by the barrel.” Translation: An editor can always get the last word. But when Jack published those letters to the editor, it was always without rebuttal. Even if a simple clarification could defuse their complaint — and make us look better — Jack would have none of it. The reader gets the last word.

You see, Jack never gave up trying to turn his critics into friends.

At the time, in the mid-1980s, neutrality among Baptists seemed as pointless as it was rare. Especially for a journalist covering the SBC from within, conflict was an inescapable job hazard.

Jack’s approach of trying to turn critics into friends struck me as quixotic, just another lost cause. But looking back now, Jack’s point of view told me something about his theology, and a lot about his view of people. None are beyond hope and reason.

The birth of ABP

In 1990, after the firing of the two editors of the SBC-owned Baptist Press, Associated Baptist Press was formed — a truly independent news collaborative to serve Baptists. They came to Florida a couple months later looking for ABP’s first executive editor, and I jumped at their offer.

“What I didn’t find out until later is that ABP came looking for Jack.”

What I didn’t find out until later is that ABP came looking for Jack. They weren’t even considering me. It was Jack who convinced them to. Once again, Jack saw what I could become. He knew I would flourish in a job that placed a premium, not penalty, on hard news free from the scrutiny of leaders who think the facts need a few coats of varnish before they’re ready for Christian consumption.

The time Jack and I worked together was a mere five years — just a fraction of my career — and that was 30 years ago. One or two other colleagues might rival Jack for influence in my life. But the lessons I learned from him about our profession and life still ring as loud and as clear as ever across my mental landscape.

The whole time Jack and I worked together, there was a campaign afoot to get us both fired. Maybe my departure lowered the temperature some, but I doubt it. There was always other cannon fodder lying around for critics to use.

By the early 1990s, websites and other digital media were emerging as affordable options to print publications. Sinking circulation was an albatross around the neck of almost every print editor at the time, religious and secular. And it was a bad time for anyone paying for paper or postage.

Finally, “the day came that the SBC controversy had taken too great a pound of flesh from him,” Lindsay recalled. He resigned from the Witness in August 1994.

I certainly couldn’t fault with Jack for resigning. His board of directors was relentless. In one meeting after another, directors criticized his editorials, his use of ABP stories, and circulation, which had dropped by half.

When I left the Witness in 1991, Lindsay assumed my duties with the title of assistant editor, despite no formal journalism education. “Jack gave me almost unlimited discretion about what went into the paper and supported me.

And when Jack left three years later, she was named interim editor by the directors.

After the Florida Baptist Witness, Lindsay ran her own design business until I hired her at ABP to help us launch FaithWorks magazine. She produced several magazines and other publications during her career and also served in managerial roles.

After Jack resigned from the Witness, he and his wife, Shirley, returned to Birmingham, where he worked for Samford University, his alma mater, in various communications roles until retiring in 2003.

Return to Alabama

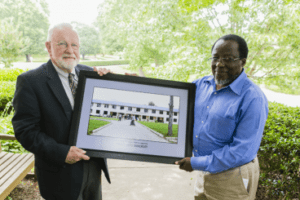

In 2015, Mount Meru University in Arusha, Tanzania, named a new education building in honor of Jack Brymer, in recognition of his years of work to support the school.

A private burial service for Jack was held Nov. 1 at Baptist Church of the Covenant in Birmingham. A public memorial will be scheduled for a later date.

Jack was born May 20, 1936, in Jefferson County, Ala., the third of six children. He is survived by his wife of 64 years, Shirley Jarman Brymer, who lives in a Birmingham nursing home; a son, Jack Jr.; two daughters, Vicki and Carissa; eight grandchildren and nine great grandchildren.

Mark Baggett, son of Jack’s predecessor at The Alabama Baptist and a longtime friend of the Brymers, called Jack “one of the pivotal figures” in Baptist journalism.

“Jack was a loyal friend and wise mentor to so many here,” said Mark, a recently retired professor of English and law at Samford. “But above all, he was an incredibly grounded person. Jack not only was a truth-teller, but he was one who has lived it.”

Dan Martin, one of the Baptist Press editors fired in 1990, was a journalism colleague and friend of Brymer’s for many years.

“Jack was a true professional,” he said. “I always enjoyed being around Jack, and often called him when I was emotionally down. He invariably had a positive — and generally funny — response. I was blessed by Jack.”

Greg Warner served as executive editor of Associated Baptist Press (now Baptist News Global) until his retirement. He lives in Jacksonville, Fla.