Another Black woman has been called “Jezebel,” a racial stereotype and slur that historically and persistently has been used to obfuscate the truth, promote and justify racial inequality and sexual violence against Black women. According to Baptist News Global, two pastors called Vice President Kamala Harris “Jezebel.”

The “Jezebel” stereotype is one of three pernicious racist and sexist stereotypes that have been used to rationalize and justify slavery and to spur racist and sexist perceptions and treatment of Black women. The three are the “Mammy,” “Sapphire” and “Jezebel” stereotypes. Gloria Ladson-Billings and Carolyn M. West, as well as many others, have written that these stereotypes originated in American slavery and continue.

The three stereotypes

“Mammy” is a slavery construct of Black women that “distorts the notion of caregiver,” Ladson-Billings wrote. Mammy is generally characterized, as a “grossly overweight,” “jolly,” “unattractive dark-complexioned woman,” and “asexual — living only to serve the master, mistress and their children.” She is “even neglectful of her own children and family while simultaneously overly solicitous toward whites.” The mammy image is the old Aunt Jemima, the Black woman wearing the kerchief on her head and wearing an apron perpetually smiling on a pancake box.

West adds: “There is little historical evidence to support the existence of a subordinate nurturing, self-sacrificing Mammy figure. Enslaved women often were beaten, overworked and raped. … In response, they ran away or helped other slaves escape, fought back when punished, and in some cases poisoned slave owners.

According to West, the Mammy stereotype was a lie. A jolly, smiling, fiercely loyal Mammy was created so we could believe slavery was a humane institution.

Hattie McDaniel in “Gone with the Wind.”

Deborah Gray White states that even the name “Mammy” is “steeped in material sentiment. Mammy is steeped with imagery of “surrogate mistress and mother.” Hattie McDaniel played a fictional “Mammy” in Gone with the Wind.

Sapphire is a construct that labels Black women as “stubborn, bitchy, bossy and hateful.” She “lacks the requisite femininity to make her attractive to any man,” Ladson-Billings writes. The Sapphire construct suggests that Black women are the reason for the “enmity between Black men and women.” The “Sapphire” name traces its origins to the 1950s television character on the Amos and Andy show.

According to West, during slavery the standard for femininity for white women (“passivity,” “frailty” and “domesticity”) did not apply to Black women: “They (Black women) were characterized as strong, masculinized workhorses who labored with men in the fields or as aggressive women who drove their children and partners away with their overbearing natures. The reality is that slaveholders sold Black women’s children and husbands away, which caused unimaginable grief and understandable anger.”

“Aunt Ester” character in “Sanford & Son.”

According to David Pilgrim, the “Sapphire” name is a “slur, insult and label designed to silence dissent and critique.”

Blair Kelly, associate professor of history at North Carolina State University, associates the “angry Black woman” trope to minstrel shows in the 19th century, when white men painted their faces black and mocked African Americans.

Former President Donald Trump referred to then-Sen. Kamala Harris as “angry,” “nasty” and a “mad woman.” He said she was “probably nastier than even Pocahontas to Joe Biden” during the Democratic debates, referring to Sen. Elizabeth Warren of Massachusetts, a white woman.

Tamara Winfrey Harris, a Black woman and author of The Sisters Are Alright: Changing the Broken Narrative of Black Women in America, has stated that the tactic of depicting Black women as “angry” and “mad Black women” describes the use of this language. This practice dates back to slavery, she notes, and is a bully tactic to intimidate Black women who enter the mainstream space and to try to force them to “shrink themselves, to not get that blowback” or “to stay silent” when Black women have every right to speak out or “to swallow their anger,” even when Black women have good cause to be angry.

Jezebel is a slave construct and stereotype that paints Black women as evil and immoral. The Jezebel stereotype is “synonymous with promiscuity,” having “an insatiable sexual appetite,” and “someone who uses sex to manipulate men,” Ladson-Billings writes. She is a “conniving temptress who cannot be trusted.” Accusing Black women of these traits and calling them “Jezebels” also attempts to connect Black women to the infamous “treacherous” queen in the Bible called “Jezebel,” who is accused of having “turned the heart of her husband, King Ahab, away from the worship of the one true God and righteous living.”

Movie poster courtesy of Ferris State University

Reproduction and having a constant supply of slaves was essential to the institution of slavery. Pilgrim states that enslaved young Black girls were encouraged to have sex as part of their “socializations” as future “breeders.” When young Black girls became pregnant during slavery, this was just seen as evidence of their insatiable sexual appetites and their “Jezebel” nature.

Deborah Gray White, providing detailed accounts of slave women and the culture of slavery, says that the Jezebel stereotypes were meant to characterize Black women. She writes: “In every way, Jezebel was the counterimage of the mid-19th century ideal of the Victorian Lady. She did not lead men and children to God; piety was foreign to her.”

According to West, during slavery, Black women were “stripped naked, examined to determine their reproductive capacity, placed on auction blocks and sold.” She states that enslaved Black women were “coerced, bribed, induced, seduced, ordered and, of course, violently forced to have sexual relations with slaveholders, their sons, male relatives and their overseers.” The “Jezebel” stereotype, which branded Black women as sexually promiscuous and immoral, was used to rationalize these sexual atrocities.”

The Jezebel image excused miscegenation and the sexual exploitation of Black women. Southerners, needing to justify slavery and race relations, used the Mammy image to “make slavery a positive good,” with Mammy as the “maternal-domestic ideal,” White wrote.

“Southerners, needing to justify slavery and race relations, used the Mammy image to ‘make slavery a positive good.’”

All these stereotypes, constructs and images were used as tools of slavery to create lies, justify racial inequality and the sexual and economic exploitation and unjust treatment of Black women and Black girls.

Sexual and racial stereotypes migrate

One of the problems with these stereotypes and their use is not only the lies embedded in them, but the fact that these stereotypes migrate.

According to Pilgrim, “The Mammy caricatures implied that Black women were only fit for one kind of work — domestic work; thus, serving to rationalize economic discrimination against Black women in America during the Jim Crow period from 1877 to 1966, keeping Black women stuck primarily in menial, low-paying, low-status positions.”

The perception of Black women as “Jezebels” and the Jezebel stereotypes also affected Black women during slavery and post-slavery. According to Pilgrim, “From the end of the Civil War to the mid 1960s, no Southern white male was convicted of raping or attempting to rape a Black woman.”

They not only included enslaved Black women and Black girls, but these stereotypes migrated to include and sexually objectify Black girls and Black children post-slavery.

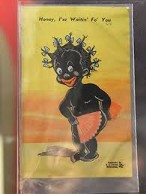

According to Pilgrim: “An analysis of Jezebel images also reveals that Black female children are sexually objectified. Black girls, with the faces of pre-teenagers, are drawn with adult-sized buttocks, which are exposed. They are naked, scantily clad or hiding seductively behind towels, blankets, trees or other objects. A 1949 postcard shows a naked Black girl hiding her genitals with a paper fan. Although she has the appearance of a small child, she has noticeable breasts. The accompanying caption reads: ‘Honey, I’se Waitin’ Fo’ You Down South.’ The sexual innuendo is obvious.

According to Pilgrim: “An analysis of Jezebel images also reveals that Black female children are sexually objectified. Black girls, with the faces of pre-teenagers, are drawn with adult-sized buttocks, which are exposed. They are naked, scantily clad or hiding seductively behind towels, blankets, trees or other objects. A 1949 postcard shows a naked Black girl hiding her genitals with a paper fan. Although she has the appearance of a small child, she has noticeable breasts. The accompanying caption reads: ‘Honey, I’se Waitin’ Fo’ You Down South.’ The sexual innuendo is obvious.

A study by the Georgetown Law Center on Poverty and Inequality also found that Black girls are “perceived” as different compared to their white counterparts. The data showed the following perceptions about Black girls compared to same age white girls:

- Black girls need less nurturing.

- Black girls need less protection.

- Black girls need to be supported less.

- Black girls need to be comforted less.

- Black girls are more independent.

- Black girls know more about adult topics.

- Black girls know more about sex.

Black girls are viewed as “more adult-like.” The study states the Mammy, Sapphire and Jezebel stereotypes “that originated during slavery have persisted into present day culture” and “underlie the implicit bias” that shape the perception of many adults of Black females as being “sexually promiscuous,” “hedonistic,” and “in need of socialization.” The study noted: “These images and historical stereotypes of Black women have real-life consequences for Black girls today.”

The report states that viewing Black girls as “less innocent” and “less feminine” than other girls likely influences how they are disciplined in school and renders them more vulnerable to criminalization.

Other reports have validated the concerns expressed in the Georgetown Law report that racial stereotypes can migrate to negatively impact Black girls in other public systems, like education.

Real-life effects today

A 2017 National Women’s Law Center report stated that Black girls are 5.5 times more likely to be suspended from school than white girls and more likely to receive multiple suspensions than any other race or gender. It also was reported that Black girls are 6.1 times more likely to be expelled from school than white girls and 2.5 times more likely to be expelled without educational support.

The National Women’s Law Center report stated that one of the barriers to school success for Black girls is the implicit and explicit bias against Black girls leading to racial and sexual stereotypes: “Stereotypes of Black girls and women as ‘angry’ or aggressive, and ‘promiscuous’ or hyper-sexualized can shape school officials’ views of Black girls in critically harmful ways.”

“One of the barriers to school success for Black girls is the implicit and explicit bias against Black girls leading to racial and sexual stereotypes.”

The report states that “implicit bias” about Black girls may lead to setting lower academic expectations for them or increase their risk of repeating a grade. For example, the report stated that although Black girls account for 15.6% of girls in school, about a quarter of Black girls were retained in first grade (24.7%), second grade (27.7%) and fifth grade (25.6%) and about a third of Black girls were retained in third grade (34.5%) and in fourth grade (39.5%). A 2014 study also showed that students who repeat a grade in elementary school are 60% less likely to graduate from high school than students with similar backgrounds who were not repeaters.

This is by no means the whole story. The Georgetown study and other studies have found that racial and sexual stereotypes about Black girls and Black women have implications and migrate to other public systems, including education. criminal justice system, health care and more.

A 2012 report by the African American Policy Forum discusses the “school-to-prison pipeline” for Black girls.

Black girls are disproportionately at risk for being the targets of physical abuse, sexual abuse and sex trafficking. A report by the Congressional Black Caucus Foundation, “Snapshot on the State of Black Women and Girls: Sex Trafficking in the U.S.” includes data that Black girls are more likely to be street trafficked at younger ages and that 57.5% of all juvenile prostitution arrests are Black children. The report explains: “To better understand the high rates of sex trafficking among Black women and girls, research has indicated the continued sexualization of Black women and girls’ bodies, which has played out since slavery. The myths around Black women and girls’ hypersexuality cannot be ignored when researching sex trafficking.

This isn’t just about the vice president

In other words, calling Vice President Kamala Harris a “Jezebel” is not just about one Black woman. Racial and sexual stereotypes migrate and affect the lives of all Black women and Black girls, inviting others to look at all Black women and Black girls as “Jezebels.”

“They are meant to cast all Black women and girls as ‘despised others,’ who are morally corrupt.”

That’s exactly what racial and sexist slave stereotypes like “Jezebel” are all about. They are meant to cast all Black women and girls as “despised others,” who are morally corrupt. They are meant to apply to all Black women, and they migrate to include Black girls.

No woman should be called a “Jezebel” or cast as a sexual or racial stereotype the way enslaved Black women were.

To make this even more alarming, just imagine the effect these stereotypes have when the comment is coming from church by a pastor or church leader. Does it add credibility to the “Jezebel” myth or cause others to repeat this racial slur? Does the use of such a slur incite violence to be perpetuated? Does this behavior by clergy give permission to use Scripture to maltreat Black women and Black girls?

Calling Vice President Kamala Harris “Jezebel” is despicable. But what about the effect on all the other Black women and Black girls?

Yvonne McLean is an attorney and member of Allen Temple Baptist Church in Oakland, Calif., where she is a Sunday school teacher and a member of the Unhoused Ministry.

Yvonne McLean is an attorney and member of Allen Temple Baptist Church in Oakland, Calif., where she is a Sunday school teacher and a member of the Unhoused Ministry.

Related articles:

SBC pastor calls Vice President Kamala Harris a ‘Jezebel’ two days after inauguration

A second SBC pastor in Texas called Vice President Kamala Harris ‘Jezebel’

Pastors Buck and Swofford, get the biblical story of Jezebel straight!

When you call the vice president ‘Jezebel,’ you are acknowledging her power

Sources:

- Gloria Ladson-Billings (2009) “‘Who you callin’ nappy-headed?’ A critical race theory look at the construction of Black women.”

- Carolyn M. West (2008) “Mammy, Jezebel, Sapphire, and their homegirls: Developing an ‘Oppositional Gaze’ Toward the Image of Black Women.”

- Deborah Gray White (1999) Ar’n’t I a Woman? Female Slaves in the Plantation South.

- David Pilgrim, professor of sociology, Ferris State University, the Jim Crow Museum of Racist Memorabilia regarding “The Mammy Caricature,” and “The Jezebel Stereotype,” and “The Sapphire Caricature.”

- Brandi Collins-Dexter, senior campaign director at Color of Change, in “Serna Williams and the ‘Trope of the Angry Black Woman, by Ritu Prasad, BBC News.

- “Girl Interrupted: The Erasure of Black Girls’ Childhood,” (2017) by Rebecca Epstein, Jamilia Blake, Thalia Gonzalez, Center on Poverty and Inequality, Georgetown Law.

- National Women’s Law Center Report, “Race, Gender and the School-to-Prison Pipeline: Expanding Our Discussion to Include Black Girls,” by Monique W. Morris. http://schottfoundation.org/sites/default/files/resources/Morris-Race-Gender-and-the-School-to-Prison-Pipeline.pdf.

- National Women’s Law Center Report “Stopping School Pushout for Girls of Color.”

- Congressional Black Caucus Foundation, “Snapshot on the State of Black Women and Girls: Sex Trafficking in the U.S.” by Samantha Davey.

- “Trump Deploys the ‘Angry Black Woman’ Trope Against Kamala Harris” (2020), by Derrick Clifton.

- Michelle S. Jacobs, “The Violent State: Black Women’s Invisible Struggle Against Police Violence.”