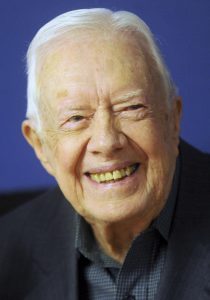

Baptist leaders are remembering President Jimmy Carter as a Christian example of faithfulness, compassion and justice — and as a staunch advocate of a traditional view of religious liberty.

Carter, the nation’s 39th president, died Dec. 29 at age 100.

In a century of living, the Georgia peanut farmer experienced tremendous change not only in his life but in the culture around him. A devout Southern Baptist at the time of his presidential election in 1976, Carter and his wife, Rosalyn, became part of the exodus of “moderates” from the nation’s largest Protestant denomination due to the “conservative resurgence” that swept the SBC in the late 20th century. They joined the Cooperative Baptist Fellowship, a group founded in 1991 out of the schism in the SBC.

That was one of many sweeping changes Carter experienced from the time of his birth in 1924, when Calvin Coolidge was elected president of the United States. Also in the year of Carter’s birth, the FBI was established with J. Edgar Hoover as its first director, Congress passed the Indian Citizenship Act, granting citizenship to all Native Americans born in the United States; Vladimir Lenin died and Josef Stalin became leader of the Soviet Union; Macy’s put on its first Thanksgiving Day parade; and the first round-the-world flight was attempted by four U.S. Army Air Service airplanes, a journey that took 175 days.

Seismic world change also defined Carter’s presidential term, leading to his failed reelection bid in 1980, when Ronald Reagan was elected president — in part due to rampant hyper-inflation and in part due to the Iran Hostage Crisis, which was precipitated by the U.S.-backed shah of Iran being deposed by revolutionaries.

In an article for The Atlantic, Russell Moore quotes advice Carter gave him in 2016 when Donald Trump was elected president the first time. Moore, then head of the SBC Ethics and Religious Liberty Commission, was a vocal never-Trumper among conservatives.

“Everything has a way of coming back around. What seems unstoppable and inevitable never is.”

“These things have happened before,” Carter told Moore. “Everything has a way of coming back around. What seems unstoppable and inevitable never is.”

Moore explains: “I thought to myself, Well, he should know. Carter had experienced himself how quickly political realities change.”

A consistent trait

Amid a life of change, Carter held fast to his Christian faith and his Baptist identity. He was credited with bringing the term “born again” into common American conversation in the 1976 election.

Former U.S. President Jimmy Carter works at a Habitat for Humanity building site in Memphis, Tenn., Nov. 2, 2015. . (AP Photo/Mark Humphrey)

“President Carter will be remembered for living out his devout Baptist faith through his pursuit of peace and support for human rights as well as acts of service, such as building homes for Habitat for Humanity. When it came to following Jesus, Carter walked the walk,” Amanda Tyler wrote for Time magazine. Tyler serves as executive director of Baptist Joint Committee for Religious Liberty and leads the Christians Against Christian Nationalism campaign.

“Lesser known, and particularly relevant for American politics today, is our 39th president’s commitment to the Baptist value of religious liberty,” she added. “The United States’ most religious president in recent memory was also the most committed to the separation of church and state.

Tyler urged: “I hope we can pause for a moment as we remember the life of Jimmy Carter to consider how different the relationship between religion and government would look in the United States if our political leaders would follow Carter’s example.

“Not only would our nation’s commitment to religious freedom for all — including those who want to be free from religion — be strengthened, but I also believe Christianity would flourish. Baptists believe that faith should be freely chosen, not imposed on people by the government. … We don’t need theocracy to revive American Christianity; we need people to act like Jesus.”

Rural Georgia roots

The future president learned these values in a Christian home in rural Georgia. When he wasn’t helping his father on the family’s peanut farm, he fished or played in the woods with his friends, most of whom were Black.

Racial segregation was part of life in the South in the 1920s, and he soon learned how race can divide people when his Black playmates showed deference to him as they grew older. His deep friendships with those Black neighbors affected him profoundly, but Carter said his experience in the U.S. Navy as President Harry Truman desegregated the civil service and military solidified his family’s commitment to racial equality.

Jimmy and Rosalynn Carter wave to the assembled Democratic delegates in Madison Square Garden July 15, 1976, after Carter accepted the party’s presidential nomination. (Getty Images)

Later, as governor of Georgia, Carter sought to heal the state’s racial divisions. He increased the number of African American state employees by 40% and equalized funding of schools in rich and poor districts. He also created new educational facilities for prisoners and the developmentally disabled.

In his 1976 presidential campaign, Carter embraced the power of the 1965 Voting Rights Act, which enfranchised millions of African Americans and expanded protections for Latinos and language minority groups. Consequently, he carried every Southern state except Virginia by winning 95% of the Black vote, compared with 45% of the white vote.

As an active and visible Baptist layman, Carter developed a decades-long friendship with Jimmy Allen, president of the Southern Baptist Convention in the late 1970s. Together, they dreamed up what came to be known as Bold Mission Thrust, the SBC’s ambitious program to spread the Christian gospel around the world by the year 2000.

Along the way, the Carters demonstrated their commitment to social justice and basic human rights. They championed those themes during their years in the White House, and their resolve deepened after his presidency ended. In 1982, they founded the Carter Center to further their commitment to global human rights and justice.

In 1984, the Carters worked on a Habitat for Humanity project in Americus, Ga., that began their long-term involvement with the organization and took them on builds across the nation and around the world. Through the Carter Center, they also worked to eradicate Guinea worm disease, a parasitic infection that once incapacitated up to 3.5 million people every year in Africa and Asia. Thanks to their efforts, only 14 cases were reported worldwide in 2023.

Carter also traveled extensively around the globe, working to ensure free and fair elections. His championship of democracy stemmed from his Christian belief that all people are worthy of decency, respect and a voice in their government.

New Baptist Covenant

Jimmy Carter speaks at the first New Baptist Covenant meeting, with President Bill Clinton behind him and Mercer University President Bill Underwood at right. (Photo: Mercer University)

Carter’s faith informed every part of his life, as evidenced by his stalwart commitment to racial justice. Consequently, he became saddened by the persistent racial and theological divisions between Baptist communities in the United States, and he decided to do what he could to heal those divides.

Beginning in 2006, Carter brought together leaders representing more than 30 Baptist organizations and more than 20 million people. Although Southern Baptists refused to participate, the others took up Carter’s challenge to explore new opportunities for fellowship and cooperation. At Carter’s urging, they developed the New Baptist Covenant, a multi-racial network of local ministry action.

In addition to a national gathering in Atlanta in 2008, New Baptist Covenant helped create inclusive Baptist communities across the country. Congregations from the same city — sometimes as close as down the street from one another — that historically remained segregated joined forces to nurture relationships and to transform their communities. Their shared Covenant of Action projects have included literacy programs, food justice initiatives and economic development advocacy.

Aidsand Wright-Riggins, former executive director of New Baptist Covenant, remembered Carter’s inspiration and persistent encouragement for racial inclusion.

Hannah McMahan King (left) and Aidsand Wright-Riggins previously served as co-executive director of New Baptist Covenant.

“In a series of conferences and summits, President Carter engaged these action-based covenants to reflect on Jesus’ mission of reconciliation through just relationships. He encouraged participants to acknowledge differences, confess our complicity and their evolution and to take steps toward transformation,” said Wright-Riggins, a former American Baptist Churches executive.

“President Carter lived his faith. Always the teacher, Jimmy Carter encouraged right practices over orthodoxy.”

Hannah McMahan King, former New Baptist Covenant executive director, said Carter’s Baptist upbringing shaped his moral vision, which propelled him to pursue justice and to seek the welfare of vulnerable people — such as women and racial minorities — whom others often overlook.

“It was always striking to me how much his Baptist formation was part of his life,” she said. “Even his early participation in RAs (Royal Ambassadors, a missions program for boys) provided a direct call for him to engage in endeavors to help the world. This coalesced into something he took very seriously.”

She illustrated how Carter advocated for women by describing her first meeting as the young executive director of New Baptist Covenant, when Baptist notables from across the country gathered at the Carter Center. Most of them did not know her, and several began giving her their coffee orders.

“So, I was scrambling around, getting their coffee,” she said. “And then President Carter called me over to sit beside him. He turned to me and said, ‘Hannah, what are we going to do today?’ You could see their jaws dropping. Even in small ways, he always was watching out for how to be in league with people others didn’t have an eye on.”

“President Carter sat with leaders from around the world, trying to find a way for peace to break out and justice to roll down,” she added. “That translated into the work he did with New Baptist Covenant. He loved his neighbor by participating with God in securing their welfare.

A prophet without honor

After his 1976 election, Carter quickly fell out of favor with his own faith group, the SBC, which already was changing due to the influence of Jerry Falwell’s Moral Majority and the Religious Right movement.

US Presidential candidate Jimmy Carter with his wife Rosalynn Carter and their daughter Amy at the Baptist church in his hometown of Plains, Georgia, 1976. (Photo by Michael Brennan/Getty Images)

From 1980 forward, the evangelical vote began merging with the Republican Party, ostensibly over the issue of abortion but also due to white Southerners’ fears about racial equality.

Writing for The Towers, a publication of Southern Baptist Theological Seminary, Chris Fenner explained the changing relationship between the Carters and the SBC.

In 1977, Carter participated in a video titled “In an Act of Love” shown at the 1977 SBC annual meeting in Kansas City, promoting the new Mission Service Corps of the SBC Home Mission Board. The initiative proposed to recruit 5,000 volunteers to serve as short-term missionaries.

The next year, Carter spoke at an event related to the 1978 annual meeting in Atlanta, organized by the National Conference of Baptist Men. There, “he raised issues such as human rights, peace, poverty, the proliferation of weapons, and terrorism, which he felt were inherently moral problems.”

In 1982, while moderates still controlled the SBC’s institutions, Jimmy and Rosalynn Carter were presented the SBC Christian Life Commission’s Distinguished Service Award. And in 1984, Rosalynn Carter received the Distinguished Christian Woman Award from the Woman’s Committee at Southern Seminary.

There, she made a plea for an egalitarian perspective that just a few years later would be wiped out by a new conservative administration at the SBC’s flagship seminary: “With the time-proven ability of women to share equally all loads and responsibilities with men, it seems we should move beyond resolutions and endless talking, and simply encourage all Americans, male and female, to develop their talents to the fullest, to become leaders based on merit, not on sex.”

And then in spring 1992, Jimmy Carter delivered the commencement address at Southern Seminary, an honor related to his pastor — Dan Ariail of Maranatha Baptist Church in Plains, Ga. — being among the doctor of ministry graduates.

“A key theme of his address was the need for Christians to band together to alleviate poverty.”

“A key theme of his address was the need for Christians to band together to alleviate poverty,” Fenner said. “He also expressed his growing disenchantment with the denomination, saying: ‘Whenever I tell anybody that I’m a Southern Baptist … it’s treated as something of a joke. ‘Southern Baptist’ has been equated with schism, or divisions, or incompatibility. … The historic image of Southern Baptists as those who are dynamic missionaries for Christ, in places where we are needed … that image has changed.’”

The final straw for the Carters — as for many other disaffected Southern Baptists — was adoption of the 2000 version of the Baptist Faith and Message doctrinal statement. The former president sent a letter to Southern Baptists that explained: “I have been disappointed and feel excluded by the adoption of policies and an increasingly rigid Southern Baptist Convention creed, including some provisions that violate the basic premises of my Christian faith.”

Writing for Southern Seminary in 2016, Fenner portrayed Carter as being out of line with the SBC more than the SBC being out of line with Carter’s childhood faith.

An interview with seminary President Al Mohler “was a thoughtful and respectful dialogue about Jimmy Carter’s views of the Bible and his experience as ‘the world’s most famous Sunday school teacher.’ While it was clear that Carter has a deep love for his faith, it was also clear that his faith is not compatible with the current tenets of the denomination that had shaped his early life and career.”

A few weeks ago, Mohler gave a lengthy interview to a conservative podcaster and was asked if he think Carter is truly “born again.” Mohler replied: “I have to hope and pray.”

Mercer ties

The only board Carter ever served on after leaving the White House was that of Mercer University, a Baptist heritage school in Macon, Ga., which is 85 miles from Plains, Ga. Carter was elected to the board of trustees in 2012 and then was named a life trustee in 2017.

“President Carter, as with every endeavor he pursued, was an active, engaged trustee,” said Mercer President William D. Underwood. “Until his health began to decline in 2019, he never missed a board meeting. He asked tough questions, offered keen insights, and took every opportunity to advance Mercer and its mission. He offered wise counsel to me and was a good friend. His death leaves a significant void in the Mercer family. With profound gratitude for the life he lived, we offer our prayers to the Carter family for peace and comfort in this time of loss.”

Rosalyn and Jimmy Carter are shown in front of the Mercer Medicine clinic in Plains with School of Medicine Dean Jean Sumner and Mercer University President William D. Underwood. (Photo: John Knight/Mercer)

In the mid-1970s as governor of Georgia, Carter authorized the initial state funding that created the Mercer University School of Medicine, which opened in 1982. During his tenure on the Mercer board, he was a strong advocate for the School of Medicine’s mission to prepare primary care physicians for rural and other underserved areas of Georgia. As a trustee, President Carter made the motion to build a four-year campus of the School of Medicine in Columbus to provide more physicians for the state. It opened in 2022.

Underwood recalls that in 2018, he got a call from Carter asking for help in recruiting a physician to Plains, which had recently lost its only doctor. A couple of weeks passed and Carter followed up with an email that simply read, “Bill, where’s our doctor?” That led to the School of Medicine opening its first rural clinic in Plains, staffed with a physician and nurse, within weeks of President Carter’s request. Mercer Medicine now has six rural clinics across Georgia and more locations under consideration.

Carter was also a strong proponent of Mercer’s international service and research initiative, Mercer On Mission, which has deployed hundreds of Mercer students and faculty to dozens of countries around the world to improve the human condition.

In a statement to BNG, Underwood explained: “Whether it was seeking to bring peace to quarreling Baptists or bring heath care to rural communities through our School of Medicine, President Carter wouldn’t take ‘no’ for an answer. Jimmy Carter lived the gospel.”

Other tributes to Carter

Many other leaders offered commendations on Carter’s life and witness.

Daniel Vestal, former executive coordinator of CBF, remembered his friend as “a shining light that illumined this dark world.”

“As president, he was a fierce champion for human rights,” Vestal said. “As a world statesman, he was a peacemaker. As a humanitarian, he worked tirelessly to eliminate poverty and disease. As a man of faith, he sought to bring understanding between people of different faiths, especially between Jews, Christians and Muslims. As a human being he was an exemplar of faith, hope and love.

“He was a person of prayer but also a person of action.”

“Jimmy Carter had that rare ability to combine public advocacy and practical solutions to the most complex problems. He believed in racial reconciliation, affordable housing, religious liberty and social justice. He was a person of prayer but also a person of action. He loved humanity, be he also loved people as individuals.”

Stan Hastey, former Washington bureau chief for Baptist Press and a senior staff member at Baptist Joint Committee for Religious Liberty during the Carter administration, recalled Carter’s grace under pressure, especially as he endured some of the greatest stress imaginable.

“Jimmy Carter’s equanimity is what most stood out for me in covering his presidency. His calmness, civility and courtesy were constant, no matter the situation or audience,” Hastey said. “Whether interacting with other world leaders, or in news conferences or one-on-one interviews, he exercised the same self-control that these days is often referred to as ‘non-anxious presence.’ This was perhaps his finest quality as a leader.”

Hastey, who retired after serving as the founding executive director of the Alliance of Baptists, recalled Carter’s tenacity and humility through the most trying episode of his presidency.

“Between Nov. 4, 1979, when a mob of Islamic fundamentalists stormed the U.S. embassy in Tehran, Iran, taking hostage 52 American personnel, and Jan. 20, 1981, when his successor, Ronald Reagan, was inaugurated, Carter was consumed with the captives’ release,” Hastey said. “Put another way, for 444 of his 1,460 days in office, the Iran hostage crisis hung over the Carter presidency, overshadowing everything else, be it an accomplishment or a disappointment.

“More than any other crisis during his time in office, it was the humiliation of the capture and torture of these diplomats and military attaches over such an agonizingly long time that led to his defeat. It is said that he was up all night at the White House on the eve of Ronald Reagan’s inauguration, making a barrage of phone calls in a desperate, last-minute effort to secure their release, an effort that in fact succeeded. Yet so consumed with hatred of Carter was the Ayatollah Khomeini that he delayed the hostages’ release until moments following Reagan’s swearing-in. To his great credit, President Reagan immediately asked Carter to travel to the U.S. Air Force base in Wiesbaden, Germany, to meet the hostages and welcome them home.

“In an interview with Baptist Press four months after leaving office — the second he had granted in his post-presidency — Carter said Jan. 20, 1981, had been ‘one of the happiest days of my life.’ The hostages’ release, he added, was an answer to prayer. ‘So, I didn’t go out of office at all with a feeling of despair or anguish or even of thanksgiving for the relief of burdens,’ he declared. ‘I enjoyed the presidency, and I appreciated every day the chance to serve.’”