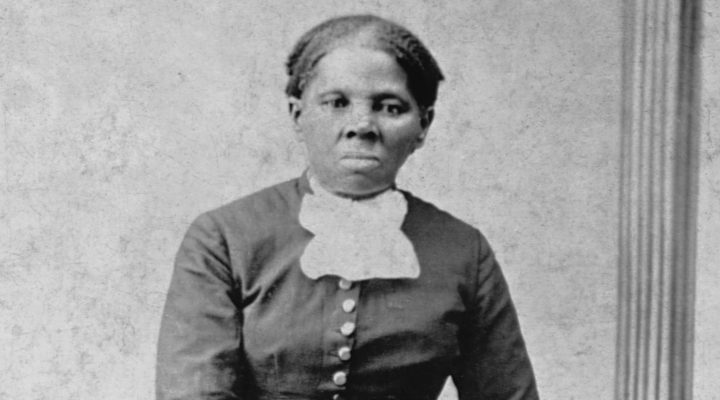

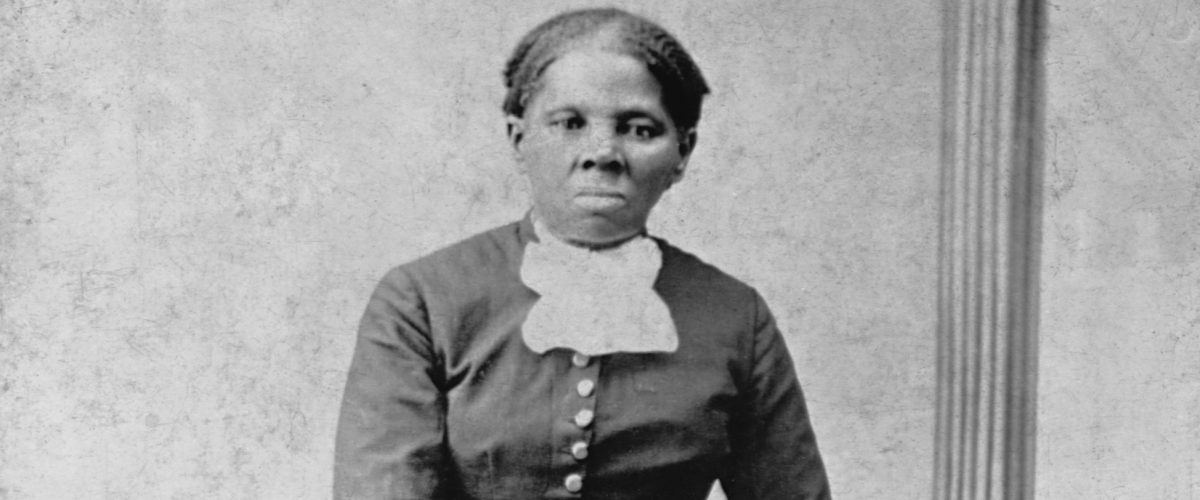

“There were two things I had a right to, liberty or death; if I could not have one, I would have the other.” Harriet Tubman (c. 1822-1913)

Born into slavery in Maryland around 1822, Harriet Tubman dreamed of freedom. In 1849, fearing she was about to be sold, she escaped, heading for Pennsylvania. And she made it, later recalling: “When I saw that I had crossed the state line, I looked at my hands to see if I was the same person. There was such a glory over everything; the sun came like gold through trees, and over the fields, and I felt like I was in heaven.”

Not content with her own freedom, Tubman made 19 trips back to the South and brought some 70 to 90 enslaved sisters and brothers to freedom. Responding to the Fugitive Slave Law (passed in 1850), she helped escapees reach Canada utilizing the Underground Railroad with its many Quaker “conductors.” The North Star was her GPS for navigating those journeys.

In 1859, Tubman, still longing for emancipation, said of it: “God’s time (emancipation) is always near. He set the North Star in the heavens. He gave me the strength in my limbs. He meant I should be free.”

“God won’t let master Lincoln beat the South till he does the right thing.”

As the Civil War got under way in 1861, Tubman criticized President Abraham Lincoln’s hesitancy to move toward emancipation, asserting: “God won’t let master Lincoln beat the South till he does the right thing. Master Lincoln, he’s a great man, and I am a poor negro; but the negro can tell master Lincoln how to save the money and the young men. He can do it by setting the negro free.”

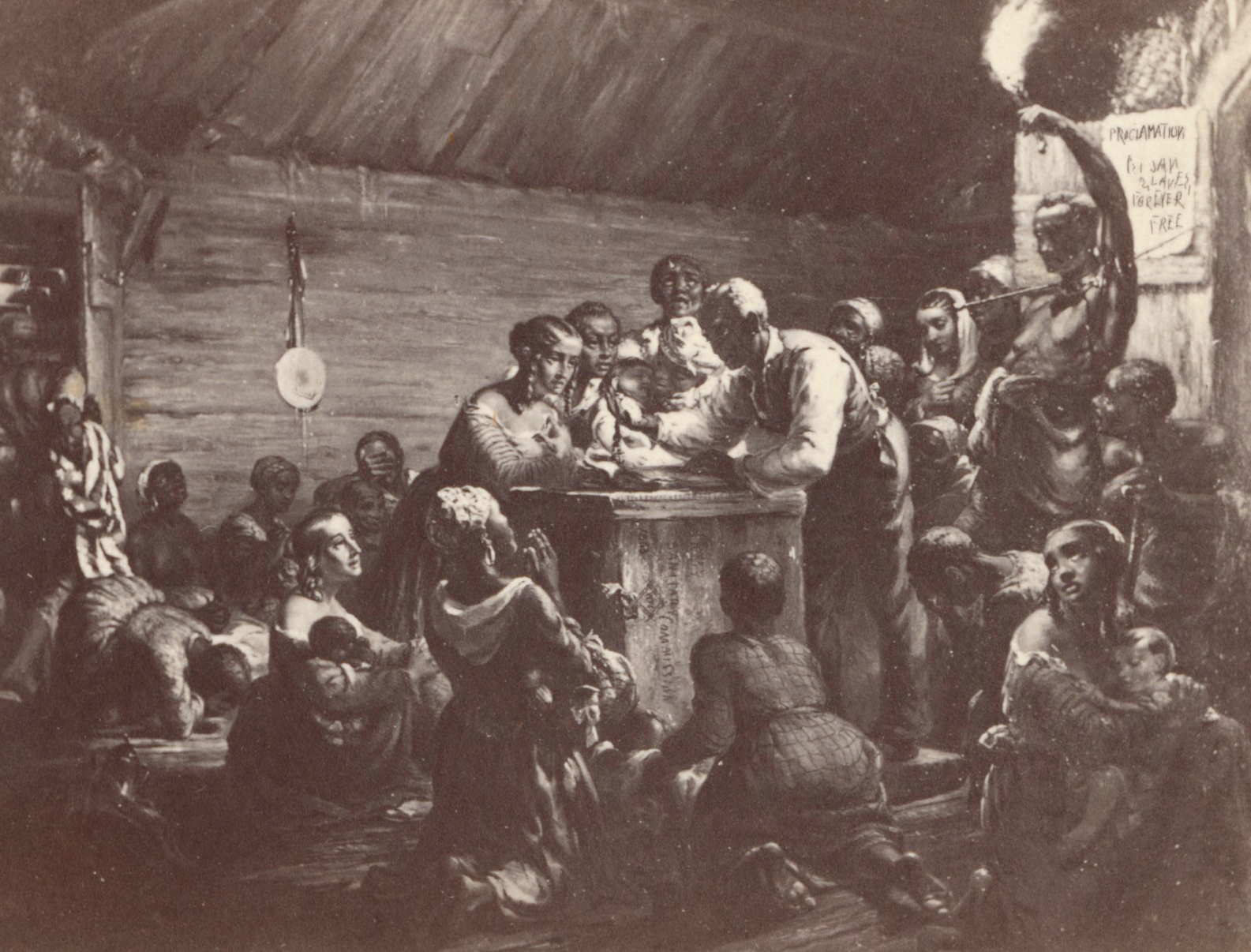

Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation, declaring all slaves in the Confederate states to be free, went into effect at midnight Jan. 1, 1863. On Jan. 31, 1862, the great Frederick Douglass declared: “It is a day for poetry and song, a new song. This cloudless sky, this balmy air, this brilliant sunshine … are in harmony with the glorious morning of liberty about to dawn up on us.” Watch night services in Black churches anticipated the moment.

“Waiting for the Hour,” Carte-de-visite of an emancipation watch night meeting 1863. Collection of the Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture

Such liberty was not fully implemented post-Appomattox until June 19, 1865. On that date General Gordon Granger and 2,000 Union soldiers entered Galveston Bay, solidifying emancipation for 250,000 Black people in Texas, the last vestige of American chattel slavery.

Juneteenth celebrations broke out among the formerly enslaved, many sponsored in Black churches and continued annually, spreading throughout the country. What many call “America’s second Independence Day,” Juneteenth became a national holiday in 2021. As the nation learns to share in those celebrations, it seems important to give voice to some of the 19th century individuals who lived through slavery and into liberation.

After their emancipation, many ex-slaves recounted their long, personalized exercise of dissent against the South’s Peculiar Institution. In his National Book Award study, Been in the Storm Too Long, the Aftermath of Slavery, Leon Litwack tells of the slave woman who cooked in the “big house” of a Southern plantation. When emancipated, she reported, “You’ll never know how many mornings I spit in the biscuits and peed in the coffee.” That woman threw herself into the antislavery cause, literally!

Litwack also includes an 1865 letter from former slave Jourdon Anderson of Dayton, Ohio, to “My Old Master, Colonel P.H. Anderson, Big Spring, Tennessee.” Excerpts include:

Sir, I got your letter and was glad to find you had not forgotten Jourdon, and that you want me to come back and live with you again, promising to do better for me than anybody else can. … Although you shot at me twice before I left you, I did not want to hear of your being hurt, and am glad you are still living.. … Now, if you will write and say what wages you will give me, I will be better able to decide whether it would be to my advantage to move back again. … I served you faithfully for 32 years and Mandy (his wife) for 22 years. … At $25 a month for me, and $2 a week for Mandy, our earnings would amount to $11,680. Add to this the interest for the time our wages has been kept back and deduct what you paid for our clothing, (etc.) and the balance will show what we are in justice entitled to. Please send the money by Adams Express, in care of V. Winters, esq, Dayton, Ohio. If you fail to pay us for faithful labors in the past, we can have little faith in your promises in the future. …. P.S.—Say howdy to George Carter, and thank him for taking the pistol from you when you were shooting at me. Your old servant, Jourdon Anderson

Leon Litwack concludes, “Few individuals — white or Black — have ever articulated the meaning of freedom more clearly or more precisely than Jourdan Anderson.” Yet he notes how quickly “the state of white opinion on the post-emancipation South” adapted its racism to the changing socio-political realities, citing the assessment of the head of the Mississippi Freedman’s Bureau, who observed:

The whites esteem the Blacks their property by natural right, and however much they may admit that the individual relations of masters and slaves have been destroyed by the war and by the president’s Emancipation Proclamation, they still have an ingrained feeling that the Blacks at large belong to whites at large, and whatever opportunity serves they treat colored people just as their profit, caprice or passion may dictate.

These stories are especially important as we approach Juneteenth 2023, in a society where “an ingrained feeling” of many white people about Black people continues to haunt the American public square 160 years after emancipation.

Florida is a case in point. In January of this year, Politico reported on concern raised by “Black officials in the state from Democratic lawmakers to faith leaders,” regarding the removal of an AP Black History course from the state’s public school curriculum. State officials, including the governor, observed that it “lacked educational value” by attempting to “shoehorn in queer theory” and Critical Race Theory.

“Let us ask what other emancipations our country needs here and now.”

That action followed a 2022 law labeled the “Stop WOKE Act” that among other things forbids teaching in ways that might cause students to “feel guilt, anguish or any other form of psychological distress” based on their “race, color, sex or national origin.” Yet when the state’s governor promotes cancellation of an African American history course because it “lacked educational value” and might “shoehorn in queer theory,” or CRT, doesn’t that very action potentially cause guilt, anguish and psychological distress for certain students?

This Juneteenth, as we celebrate America’s emancipation from slavery, let us ask what other emancipations our country needs here and now. Can we secure emancipation from white supremacy? Christian nationalism? Mass shootings? Insurrections? Opioids? Voter suppression? Sexual abuse? How many Harriet Tubman’s will it take to lead us safely out of such bondage?

New York Times’ social analyst Jamelle Bouie says Juneteenth “gives us an opportunity to remember that American democracy has more authors than the shrewd lawyers and erudite farmer-philosophers of the Revolution, that our experiment in liberty owes as much to the men and women who toiled in bondage as it does to anyone else in this nation’s history.”

Harriet Tubman would have liked that idea, Abe Lincoln too, then, and now.

Blessed Juneteenth!

Bill Leonard

Bill Leonard is founding dean and the James and Marilyn Dunn professor of Baptist studies and church history emeritus at Wake Forest University School of Divinity in Winston-Salem, N.C. He is the author or editor of 25 books. A native Texan, he lives in Winston-Salem with his wife, Candyce, and their daughter, Stephanie.

Related articles:

Opal Lee may be the ‘Grandmother of Juneteenth,’ but she’s not done working for justice yet

Juneteenth and the promise of freedom | Opinion by Darrell Hamilton II

One year later, awareness of Juneteenth is growing

Juneteenth should remind us of all the things we don’t know | Opinion by Mark Wingfield

Don’t keep sweet: Why white Christians need to celebrate Juneteenth | Opinion by Erica Whitaker