Week after week, the Border Church sees migrants and would-be asylees on its southern side.

As migrant waves wax and wane and U.S. budgets rise and fall, our weekly work with migrants awaiting entry into the U.S. near San Diego shifts in various ways and needs to be done with a spirit of openness to change. Regardless, every Sunday is an opportunity to commune with people on the move from all over the world.

The following story is of a woman from Central America. Her story is as unique as her beautiful smile, but it is also a doorway into a life of hardship.

Karla is a Honduran migrant. She is the mother of three children, but that count only includes those still alive. She lives in a colonia in Tijuana with her husband and two of her kids. The remaining child survivor was given up for adoption in Honduras to keep her safe.

Karla’s story of getting to where she is has become one of trauma, loss, recovery and hope. Her whole demeanor is one of faithful resilience and hope in God. This story brings me sorrow and carries with it the greatest foundation for joy. That is because Karla is the very kind of person Border Church seeks to serve.

Members of the Central American caravan wait in line for food and other items while in a camp on October 31, 2018, in Juchitan, de Zaragoza, Mexico. The group of migrants, many of them fleeing violence in their home countries, took a rest day before resuming their march toward the United States. The Pentagon deploy up to 5,000 active-duty troops to the U.S.-Mexico border in an effort to prevent members of the migrant caravan from illegally entering the country. (Photo by Spencer Platt/Getty Images)

Karla fled Honduras for the United States in 2018. She was part of the most infamous of recent caravans, arriving during the Trump presidency. Her life in Honduras was not of affluence. In fact, she could barely get work. Like many in Central America, Karla worked as a farmer whenever she could. With the harsh weather, grueling working conditions and neocolonial exploitation, among other issues, doing farm work in a place like Honduras is not very similar to the storied notion of agriculture in the American heartland.

Honduras has high levels of poverty and inequality. More than 48% of its residents live in poverty, and rural areas have a 60% poverty rate. Only 11% of the population is middle class. There is also a lot of violence in Honduras, with more than 38 homicides per 100,000 people. Compared with the rate of 29 per 100,000 intentional homicides in Mexico or five per 100,000 in the United States, it becomes obvious why someone like Karla would so desperately want to leave.

Karla is more than a statistic, though. So were her family members who walked into a violent death. Her father, mother and brother all were killed. Karla didn’t want to be next. She already had lived in the streets starting when she was 8 years old. She already had tried to ease her troubled mind with hard drugs, becoming an addict at age 14. She wanted something better for herself.

Between her childhood and her journey north, a group of Christians from a local Honduran church gave her a home to stay in and showed her the way of Jesus. Their act saved her life. She fully believes Jesus saved her soul, too.

Sadly, the Christians who offered Karla a path to freedom from addiction through Christ didn’t have the power to keep her safe from the men who murdered her family. So, she left.

“The media coverage stirred up white fears of brown bodies on the move, but it didn’t represent this caravan as people of God on the move.”

She joined up with the 2018 caravan with music in her heart. As someone who loved Jesus now, she learned songs about him in the popular alabanza Cristiana (Christian praise) genre. Many people may recall the political furor over this massive group of travelers, but the songs of praise in some parts of the caravan were not shown in the media. The media coverage stirred up white fears of brown bodies on the move, but it didn’t represent this caravan as people of God on the move.

Women pray at the border wall.

Karla didn’t have to wander 40 years in the wilderness as the Israelites did, but she did have to wait once she crossed over to her own promised land. It wasn’t the Jordan River but a fence that a pregnant Karla had to pass through on Dec. 3, 2018.

Before too long, she was picked up by U.S. federal agents in San Luis, Ariz., and she tried to claim asylum. As happens all too often, the agents didn’t believe her claim. Instead, they threw her in la hielera (the icebox). More than that, they didn’t believe her when she cried about “un dolor que no se imagina” (“a pain you couldn’t imagine”).

Deep within her body, something was physically wrong and causing her to scream out in anguish. The agents who were witnesses to her cries did nothing to help this pregnant woman as she pled with them about an incredible amount of pain that she could not stand. They countered her cries with statements that not only dismissed her pleas but also ignored her humanity: “Eso no es nada” (“That ain’t nothing”).

“The agents who were witnesses to her cries did nothing to help this pregnant woman as she pled with them about an incredible amount of pain.”

After being transferred to the High Desert Detention Center in Adelanto, Calif., someone with the power to act finally listened. So, on the last day of the year, Karla was admitted to the hospital. Instead of ringing in the New Year with friends and family, Karla miscarried and lost her baby on a holiday that ought to be for celebrating new beginnings.

To add insult to injury, this mother, who fled her country to make a safe home for her family, had her hands and feet shackled to the bed like a criminal, even as she suffered the unspeakable loss of her baby. At her most vulnerable, Karla’s valley of the shadow of the death of her unborn child came with no human rod or staff of comfort, only criminalization and chains.

The injustice is unreal. But it is also all too real for many who flee to the U.S. for help and instead are treated horribly.

History shows the grim realities of our government’s treatment of migrants. Whether it’s the deportation of U.S. citizens under President Dwight Eisenhower’s Operation Wetback, the cold, cramped holding cells or “iceboxes” constructed during the Obama administration, or the more than 5,500 children separated from their families under the Trump administration, officially sanctioned maltreatment of migrants on U.S. territory is nothing new.

“Officially sanctioned maltreatment of migrants on U.S. territory is nothing new.”

Karla spent six months in the United States. Her modern-day dream of an exodus to a land flowing with milk and honey came true in the scantest of ways, for she was barred from partaking in its bounty.

Many migrants and asylum seekers are fleeing the terrifyingly likely prospect of being murdered. Others seek to escape poverty and the brunt of global economic injustice, which has some roots in past U.S. corporate and government interference in other sovereign territories.

When I imagine what I would do in these situations, I most likely would flee. You probably would, too. I can only imagine what I would then do once the so-called “shining city on a hill” pushed me back down.

What would I do for my family if the actions of the country I thought would be a safe haven left us caught between a fence and a hard place? I may well stay right where I ended up. Karla did precisely that. She got stuck in a new place and chose to remain. Here, she found the Border Church as a new expression of God’s basileia.

What would I do for my family if the actions of the country I thought would be a safe haven left us caught between a fence and a hard place? I may well stay right where I ended up. Karla did precisely that. She got stuck in a new place and chose to remain. Here, she found the Border Church as a new expression of God’s basileia.

In Karla’s words, when we worship at the border, we overcome the national barrier:

En el Faro se siente que no hay fronteras, aunque este ese muro ahí, se siente que no hay fronteras cuando uno está ahí. Se siente que los dos lados están unidos. A pesar del muro, se siente que no hay fronteras. Es una emoción muy bonita; ojalá que algún día quitaran ese muro.

(At El Faro, it feels like there are no borders, although this wall is there. It feels like both sides are united. Despite the wall, it feels like there are no borders. It’s a very lovely emotion. I hope that one day they will remove that wall.)

The divine wisdom of justice, faith and hope in Karla’s words ring true, but no one at the Border Church can claim responsibility for her profound thoughts. The work of God’s basileia was under way while she was living in Central America and even on the perilous path north to our border. She found these virtues on her own, through other people of faith, and from the Faithful One before she ever worshiped at the fence that held her back from what she once thought was her land of milk and honey.

“I have faith, but Karla has the type of faith that moves mountains.”

It is through Karla’s faith and hope in God that she was able to pray to have her children with her so that she could have the chance to be “una madre ejemplar” (“an exemplary mother”). It was through this faith and hope in God that she has been able to start going back to Honduras for her children “uno por uno” (“one by one”).

Here is the love of a mother and the faith of a servant of God. It is the hope in God that I yearn for and wish were always conceivable in my own life. I have faith, but Karla has the type of faith that moves mountains. Her faith is not sight totally, but it is coming to be. It is the substance of things hoped for; it is the evidence of things not yet seen.

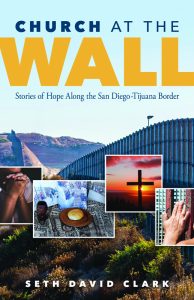

Seth Clark

Seth David Clark is lead pastor and chief operating officer of First Baptist Church of National City, Calif; adjunct faculty member at Pacific Theological Seminary; and director of the U.S. pastoral team for the Border Church. This article is excerpted from his new book, Church at the Wall: Stories of Hope along the San Diego – Tijuana Border, published by Judson Press. The Border Church meets for communion in Friendship Park, along the border fence that separates the U.S and Mexico near San Diego.

Related articles:

Have all our short-term mission trips to Latin America shaped our response to the migrant ‘caravan’? | Opinion by Chris Ellis

Faith groups amass compassion for migrant caravan as Trump amasses troops

Border Patrol targets church ministry to immigrants in Arizona