Ken Starr, who vaulted to notoriety for investigating President Bill Clinton’s sex scandal and plummeted from Baylor University’s presidency for failing to handle sexual violence complaints, has died at age 76.

Starr’s family reported he died Sept. 13 at Baylor St. Luke’s Medical Center in Houston because of complications following surgery.

Starr was born July 21, 1946, in Vernon, Texas, the son of a barber/Church of Christ minister.

Starr was born July 21, 1946, in Vernon, Texas, the son of a barber/Church of Christ minister. He grew up in San Antonio before attending Harding College, a Church of Christ school. He earned an undergraduate degree from George Washington University, a master’s degree in political science from Brown University and a law degree from Duke University.

After receiving his law license, Starr enjoyed a rapid rise in the legal community. He clerked for U.S. Supreme Court Chief Justice Warren Burger. Then he joined the Los Angeles-based Gibson, Dunn & Crutcher law firm, where he impressed colleague William French Smith, who became attorney general in the Ronald Reagan administration and took Starr to Washington with him.

Starr built upon his reputation for legal brilliance and network of connections, and in 1983, at age 37, he became the youngest person ever appointed to the U.S. Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit. Six years later, President George H.W. Bush appointed him U.S. solicitor general, the government’s top lawyer at the Supreme Court, where he was a leading candidate to be named justice in the early 1990s.

Special Prosecutor Kenneth Starr offers his testimony to the House of Representatives Judicial Committee on Nov. 19, 1998. Starr alleged in his testimony and report that President Clinton engaged in “an unlawful effort to thwart the judicial process.” (Photo by David Hume Kennerly/Getty Images)

In 1994, while working with the Kirkland & Ellis law firm, Starr became independent counsel for several investigations, including Whitewater, an examination of the real estate investments of then-President Bill Clinton and Hillary Clinton in Arkansas. That investigation led to the conviction of the Clintons’ friend Susan McDougal. Starr also investigated the death of Vince Foster, a deputy White House counsel, which his team ruled a suicide, despite vociferous complaints by conservative conspiracy theorists who claimed the Clintons covered up Foster’s murder.

Ultimately, the Whitewater investigation led to charges that Bill Clinton perjured himself in a lawsuit filed by Paula Jones, when he denied having “sexual relations” with Monica Lewinsky, a White House intern. Based on Starr’s investigation, the U.S. House of Representatives voted to impeach Clinton, but the Senate acquitted him when 10 Republicans crossed the aisle to join 45 Democrats in voting in Clinton’s favor.

The Whitewater investigation — particularly involving Bill Clinton and Lewinsky — received intense international attention, and Time magazine named Starr its Man of the Year for 1998.

Across more than a quarter-century, Starr taught constitutional law, often as an adjunct or visiting professor. He also was dean of the Pepperdine University School of Law from 2004 to 2010, when he became the 14th president of Baylor University, a Texas Baptist school in Waco.

Starr joined a deeply divided “Baylor Family,” which he continually referred to as “Baylor Nation.” The polarizing leadership of its two most recent presidents, Robert Sloan and John Lilly, and a factionalized, politicized board of regents had done little to quell controversy over Baylor’s trajectory.

Starr joined a deeply divided “Baylor Family,” which he continually referred to as “Baylor Nation.” The polarizing leadership of its two most recent presidents, Robert Sloan and John Lilly, and a factionalized, politicized board of regents had done little to quell controversy over Baylor’s trajectory.

A decade earlier, Sloan and the regents launched Baylor 2012, an ambitious plan to convert Baylor from a highly respected teaching-focused university with a strong Baptist identity into a nationally ranked Tier 1 research university with an evangelical Christian identity. The new vision drove a wedge between Baylor’s historic constituency, who treasured how the school transformed generations of students, and others who saw that vision as too small.

Starr set about trying to mend the breach by focusing on positivity and progress.

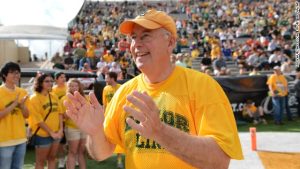

Even his detractors who met him commented on his charm and personal warmth. He seemed to revel in Baylor traditions, including joining the Baylor Line — the throng of green-and gold-clad freshman who stormed the football field before each home game. And he traveled relentlessly, meeting with alumni and other constituents on both sides of the Baylor 2012 divide.

Starr also shifted Baylor’s focus toward what could be possible when the family/nation worked together. He completed his first big focus — the $100 million President’s Scholarship Initiative — ahead of schedule. This infusion of student aid had been designed to allay concerns that Baylor 2012 had priced the university out of range of its historic student base.

Other accomplishments on Starr’s watch at Baylor included:

- Completion of McLane Stadium, a state-of-the-art football facility on the banks of the Brazos River, just north of campus, and highly visible to passing traffic on I-35.

- Establishment of the Robbins College of Health and Human Sciences, along with strengthened partnerships with the Baylor College of Medicine and Baylor Scott & White Health.

- Expansion of the Baylor Research and Innovation Collaborative in the Central Texas Technology and Research Park in Waco.

- Construction of at least nine campus buildings or complexes, plus renovation of three dorms, other buildings and campus landscaping.

- Launch of Baylor in Washington, a program that places Baylor students, faculty and alumni in the nation’s capital.

- Development of the Baylor Bound program, which helps community college students in Texas transfer to the university.

Starr’s tenure at Baylor received a feel-good public relations boost from the success of the football team. Head Coach Art Briles had arrived two years earlier, and the Bears enjoyed their first winning season in 15 years in 2010. From that point, Baylor became a Big 12 Conference powerhouse, post-season bowl winner and nationally ranked contender. Along the way, star quarterback Robert Griffin III won the Heisman Trophy, and Baylor alums on both sides of the academic divide joined together to shout, “Sic ’em, Bears!”

But football became Starr’s undoing at Baylor. The team gained a reputation for lax oversight. Charges of sexual assault against team members surfaced, and two were convicted. This opened a Pandora’s box of allegations that Baylor failed to uphold Title IX, a regulation that prohibits sex discrimination in the education programs and activities of schools that receive federal financial assistance.

But football became Starr’s undoing at Baylor. The team gained a reputation for lax oversight. Charges of sexual assault against team members surfaced, and two were convicted. This opened a Pandora’s box of allegations that Baylor failed to uphold Title IX, a regulation that prohibits sex discrimination in the education programs and activities of schools that receive federal financial assistance.

In May 2016, the Baylor regents cited a “fundamental failure” to handle sexual assault violence complaints appropriately as reason to remove Starr as president. They also fired Briles and sanctioned Athletic Director Ian McCaw, who resigned a few days later.

At the time, Starr agreed in principle to remain as Baylor’s chancellor, a position he held since 2013, and to stay on as the Louise L. Morrison Chair of Constitutional Law at the Baylor Law School. Two weeks later, Starr told ESPN he stepped down as chancellor “as a matter of conscience.” By the end of that summer, Starr also left the law school.

The Baylor statement announcing Starr’s final departure said: “The mutually agreed separation comes with the greatest respect and love Judge Starr has for Baylor and with Baylor’s recognition and appreciation for Judge Starr’s many contributions to Baylor.”

Ken Starr appears on Fox News in 2019 to say Donald Trump’s impeachment was “a very ugly chapter in our constitutional history.”

The next year, Starr joined the Lanier Law Firm. In recent years, he was a frequent guest on Fox News, often defending former President Donald Trump and speaking against Trump’s impeachment.

A Baylor statement announcing Starr’s death listed his numerous accomplishments and did not mention his departure.

It quoted Baylor President Linda Livingstone: “Judge Starr was a dedicated public servant and ardent supporter of religious freedom that allows faith-based institutions such as Baylor to flourish. Ken and I served together as deans at Pepperdine University in the 2000s, and I appreciated him as a constitutional law scholar and a fellow academician who believed in the transformative power of higher education.

“Judge Starr had a profound impact on Baylor University, leading a collaborative visioning process to develop the Pro Futuris strategic vision in 2012 that placed Baylor on the path to where we are today as a Christian Research 1 institution. Baylor University and the Baylor Family express our deepest sympathies to Alice Starr and her family, and our prayers remain with them as they mourn the loss of a husband, father and grandfather. May God’s peace and comfort surround them and give them strength now, and in the days to come.”

He will be laid to rest alongside a long list of notable Texans including Stephen F. Austin, Ann Richards and Tom Landry.

Starr’s wife of 52 years, Alice, survives him, as do his son, Randall P. Starr and wife, Melina; daughter Carolyn Doolittle and husband, Cameron; daughter Cynthia Roemer and husband, Justin; nine grandchildren; a sister, Billie Jeayne Reynolds; and a brother, Jerry Starr.

A memorial service for family only will be held at Antioch Community Church in Waco on Saturday, Sept. 24. Visitation will be held at Wilkirson Hatch Bailey in Waco on Friday, Sept. 23, from 4 to 7 pm.

According to the family, Starr will be buried at the Texas State Cemetery in Austin. That historic cemetery has strict guidelines for admittance, being reserved for present and former members of the Texas Legislature, present and former elected state officials, persons specified by a governor’s proclamation or legislative action, and “persons who have made a significant contribution to the history of Texas as specified by order of the Texas State Cemetery Committee.”

There, he will be laid to rest alongside a long list of notable Texans including Stephen F. Austin, Ann Richards and Tom Landry.

Related articles:

Kenneth Starr is doing it again | Opinion by Alan Bean

Baylor shakeup continues with Starr’s resignation as chancellor

Starr receives enthusiastic — but not unanimous — Baylor welcome