Talk about missional.

St. Paul Community Baptist Church in Brooklyn, N.Y., and its pastor, David Brawley, have made headlines for their efforts to reach out to, and transform, the communities around them.

The congregation lent its muscle to efforts to provide affordable housing and hold public housing authorities accountable for shoddy maintenance practices. It has formed active relationships with police, launched a charter school and provides finance education, nutrition and conflict resolution courses for African-American males.

And that’s just scratching the surface.

“Imagination created the energy we needed,” Brawley said.

‘Let’s be proactive’

That process was already underway when Brawley arrived at St. Paul in the 1990s.

The transformation kicked into high gear in the late 1990s when St. Paul joined East Brooklyn Congregations, an ecumenical grassroots community action group made up of more than 20 churches and ministries.

Through that organization, Brawley said, the church began forming relationships beyond its walls and having an impact citywide.

“We go through a process of house meetings and relational meetings to come up with strategies and plans,” he said.

It’s how members see where God is active in the community and where people are in need.

It was through EBC that St. Paul joined a broad-based coalition to raise money to start building affordable housing. So far, more than 3,000 units have been built and another 1,500 are on the way, he said.

A campaign also is underway to push public housing officials to address a huge backlog of repairs and upgrades.

“Half a million residents in our city live in public housing with little voice and advocacy” on issues like mold, lead paint and the growing number of children with asthmatic symptoms.

Public safety was another concern, Brawley said. Police officials were asked to partner with congregations to help residents report crimes while remaining safe themselves.

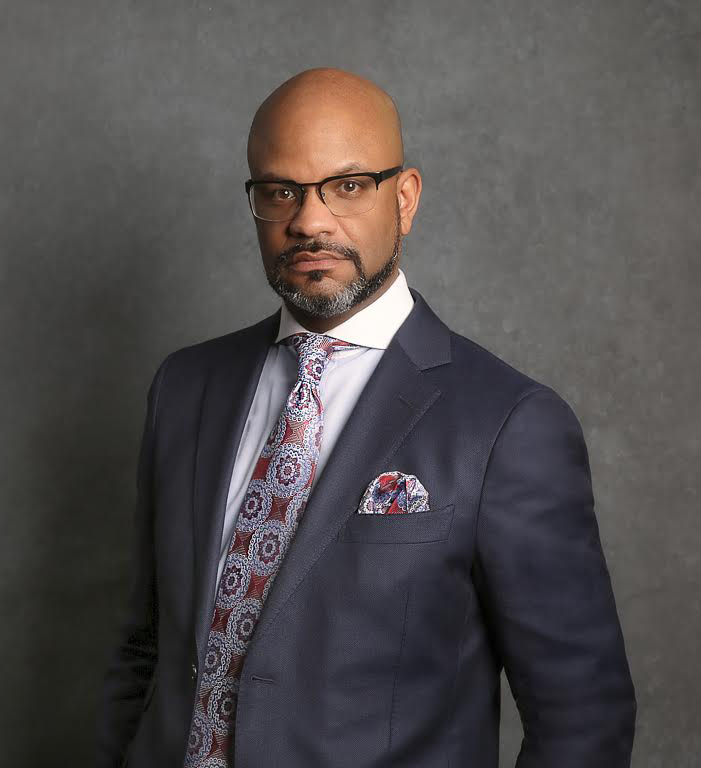

Churches in Brooklyn, N.Y., have been building relationships between residents and police, said David Brawley, pastor of St. Paul Community Baptist Church. (Photo/Otto Yamamoto/Creative Commons)

“Members of the community don’t have to go to the precinct with information,” he said. Instead, they can report issues to a church, which will relay it to police.

“It keeps folks in the community off the radar screen so they don’t have to worry about reprisals,” he said.

Law enforcement also has been embraced in an effort to prevent conflict between residents and police, Brawley said.

“We reached out and said let’s be proactive.”

‘Fireside chats with everyone’

The deal they reached requires rookie cops to visit churches to meet with residents, and especially with young black men, he said.

The meeting at St. Paul began stiffly, then warmed up as people connected.

“All of a sudden there was a relational meeting happening,” Brawley said.

St. Paul also recently hosted court proceedings for 700 people with warrants for offenses like jumping turnstiles, possessing an open beer can or riding a bike on a sidewalk. They were minor offenses, but kept people in the shadows to hide from authorities.

“Over 600 had their records expunged,” he said. “They could begin anew.”

According to Brawley, St. Paul’s secret to continual growth and scope of action is to constantly begin anew.

That process begins by involving church members in the planning process, which usually means going to their homes.

These house meetings, he said, “are powerful because it allows people to be relational where they live.”

And sometimes it’s important to look back, Brawley said. Doing so inspired the church to open a slavery museum. In September it will host the 22nd annual Maafa — an event examining slavery and racism in America.

The key to creativity was involving the entire congregation, Brawley said.

“In order to move to the next level of ministry and to reinvent ourselves, we had to re-imagine our church,” he said. “I had fireside chats with everyone in the church and asked them to dream again.”